The odyssey of restoring the most famous Roman mosaic in the world: Seven tons, two million pieces and a 2,000-year-old mortar

The National Archaeological Museum of Naples begins the restoration of the Alexander the Great mural from Pompeii, while inaugurating an exhibition about the Hellenic king in the East

The experts at the National Archeological Museum of Naples (MANN) wonder how long a 2,000-year-old Roman mortar can hold together. It was created all those years ago to join the two million pieces of the most famous mosaic of the ancient world, which weighs seven tons and shows Alexander the Great confronting the Persian king Darius III. Archaeologists are about to find out: starting this week, they are embarking on one of the most complex and difficult restoration processes in memory. It will take them at least a year.

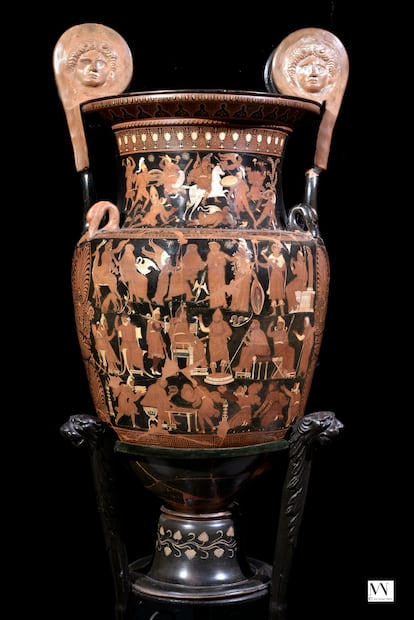

The restoration of the mosaic, which represents the Hellenic king at the battle of Gaugamela or perhaps Isos —experts are still debating it— coincides with an exhibition titled Alexander the Great and the East: Discoveries and Marvels, inaugurated this Monday at the MANN. It showcases beautiful pieces from different museums around the world, from the helmet of a Macedonian soldier that appeared in present-day Iraq, to images of war elephants, which were female elephants that went into battle with their children in order to respond more ferociously when threatened.

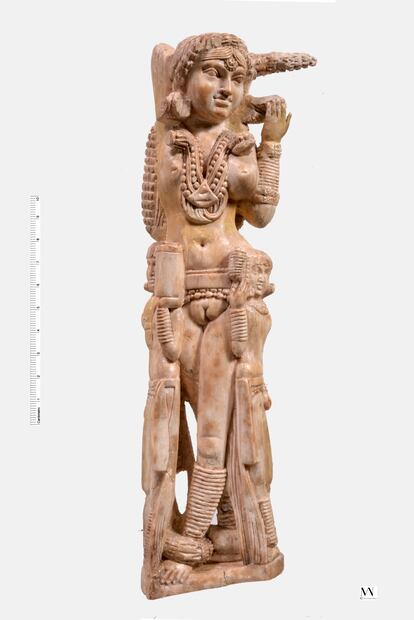

The exhibition was curated by the archaeologist Filippo Coarelli and the philosopher and writer Eugenio Lo Sardo. It is based on the idea that Alexander the Great founded a multinational empire, which brought together different creeds and peoples, which seems almost revolutionary in present-day Italy, whose government verges on xenophobia when it does not actively promote it. As he supervises the last touches, days before the exhibit’s inauguration, Lo Sardo pauses on a piece that summarizes the purpose of the show, on view until August 28. It is a marble statue from India that appeared in a house in Pompeii. “The true border of the empire was in the East. It was India,” he explains. Neither Alexander’s empire nor the Roman Empire can be understood without their relationship with the East.

But the exhibit — which this newspaper attended at the organizers’ invitation — lacks the most significant piece about Alexander owned by the MANN, the most important archaeological museum in Italy. (In addition to the pieces shown, it has in storage some 40,000 objects from Pompeii, Herculaneum and other Campania archaeological sites, just as good as the ones displayed, but impossible to exhibit without filling the galleries to the roof.)

The mosaic of Alexander was found in Pompeii’s House of the Faun in 1831, during the Borbonic excavations. Until the eruption of Vesuvius in the year 79, it was displayed in an open-air room that opened onto the garden of the domus, which belonged to a rich family. The house took up some 3,000 square meters, an entire block. Even then, when the Pompeiian mansion was inhabited, the piece was an antique: it was made at the end of the second century before Christ or the beginning of the first. As the museum’s directors explains, “they showed it like one would show a portrait of an ancestor made by a great painter centuries ago.” The main hypothesis about the authors is that they were a traveling team of mosaic artisans from Alexandria, who found a flourishing market in the Roman Empire. Other experts believe that it was created outside of Pompeii and then moved.

Though it lacked some fragments, the mosaic was excellently preserved when it was found. And the scene it showed, inspired by an earlier painting, is impressive: Alexander rides Bucephalus, charging against the soldiers of the Persian king Darius III. The mosaic reflects the violence and the movement of battle in a realistic scene full of lances, fists and swords. In both the battles of Guagamela (331) and Isos (333), Alexander defeated the Persian king. Alexander’s war garb is reconstructed stone by stone with enormous detail, with the head of Medusa in the center of his armor.

In 1843, the mosaic — measuring 2.72 by 5.13 meters — was packed and transported from Pompeii to the Royal Bourbon Museum in Naples in a cart drawn by 16 oxen. In 1845, it began to be displayed horizontally, just as it had been intended when it was created. However, in 1916, almost 100 years ago, it was hung on the wall. In recent times it had already presented some conservation problems, but above all, archaeologists were increasingly concerned that its own weight might end up damaging the delicate piece: the mortar on which it rests is the original, Roman material, and it was never designed to be exposed vertically, but on the ground. The current director of MANN, Paolo Giulierini, decided to break the Gordian knot and begin a total restoration of the piece, a process comparable to an intervention in the Mona Lisa.

“We do not know what is behind it, and it is a mortar made more than twenty centuries ago,” Giulierini explains in front of the mosaic, currently covered by an image of the same size that covers the original piece, wrapped in canvas to prevent further deterioration. Only when the curators — who are part of a multidisciplinary team that includes nine companies and institutions — manage to take it down will they discover how much the ancient material has withstood the centuries and the pressure of its own weight. To do this, they have commissioned a special, custom-made machine. They are preparing to seal off the room below because they need to secure the floor to ensure it can withstand the weight of the entire operation. Only when they remove the mosaic from the wall will they know how long the restoration will take, although they think it will be at least a year. Then they will decide whether to display it as a painting or on the ground. The process will cost at least €1 million.

The exhibition will show the restoration via a camera that joins the ancient empire of Alexander with 21st-century technology. Meanwhile, the multitude of pieces tell a story in which Alexander is not only the great conqueror, but a king who allowed himself to be influenced by those lands he occupied, who, after seizing Babylon, forced his soldiers to marry local women and to speak Persian. He himself married a woman from Bactria, the mythical Roxana. The dozens of works on display show a round-trip empire, in which art not only traveled from the West to the East, but also returned from East to West and left its mark on our culture.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.