‘Homo naledi’: Not much brain, but a lot of art

A team of paleontologists believe they have found evidence of ceremonial burials dating back 240,000 years, long before ‘Homo sapiens’ came into existence

The world of human evolution is in turmoil these days. A team of paleontologists believe they have found evidence of ceremonial burials dating back 240,000 years, long before our species, Homo sapiens, came into existence. I say ceremonial because, according to the scientists, it would not simply be a matter of burying the corpses underground, but of carrying them through a labyrinth of naturally formed tunnels in the limestone rocks of the Rising Star cave system in South Africa. The bodies appeared in fetal position and sometimes had a stone tool next to their hand. The walls are engraved with lines whose appearance is vaguely symbolic.

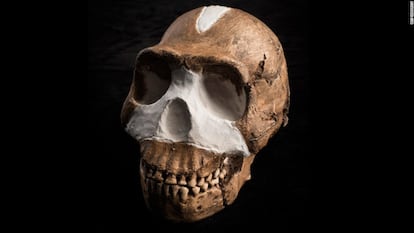

Most shockingly of all, the inhabitants of these caves had a brain the size of a chimpanzee’s. The species, called Homo naledi, was already known to scientists and constitutes one of the most puzzling mysteries of human evolution.

Our pride in our species has deceived us. We need to believe that we are qualitatively different from other creatures, but everything we know about biological evolution, which is a lot, forces us to conclude that we are not. The six or seven million years that separate us from the chimpanzee are a geological blink of an eye, barely 0.2% of the history of life. The mental faculties inherent to our species have produced poetry and art, science and literature, philosophy and politics, true, but there is no evolutionary time to perform all that intricate neural lacework with very specific and innovative strategies. The great hope for understanding our origins is that they can be explained by something as vulgar and unsexy as a massive increase in size.

And the data has been fairly consistent so far. Rounding up a little, the chimpanzee and Australopithecus had half a liter (28.4 cubic inches) of brain. Homo erectus added another half liter, which was enough to invent tools, and Homo sapiens gained half a liter more and became the master of the world. That’s a rough version of the story, but it’s quite effective in explaining why our abilities are so much higher, without us having had much time for them to evolve.

But then, how does Homo naledi fit into it all? For starters, finding a hominin with a half-liter skull that lived only 250,000 years ago already came as a shock when the species was discovered in 2014. Australopithecus had the same cranial capacity, but they became extinct millions of years ago. The other known exception is the Indonesian “hobbit” (Homo floresiensis) of which a dozen fossils have been discovered, but only one skull. And if the South African findings are now confirmed, it would turn out that half a liter of skull would be enough for mortuary rituals and even an ancestral form of art. For a large part of the profession, this does not even fit into the picture. The papers on the Rising Star cave system are still under peer review, and scientists such as María Martinón-Torres, director of the National Center for Research on Human Evolution (CENIEH) in Burgos, Spain, do not believe that the burials have been proven to be deliberate.

That’s the situation as it stands at the moment. But if it is proven that Homo naledi had a little brain and made a lot of art, we will need new theories on the evolution of the human mind. Maybe size doesn’t matter after all.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.