‘Many scientists have studied penises, but there is an incredible gap in our understanding of vaginas’

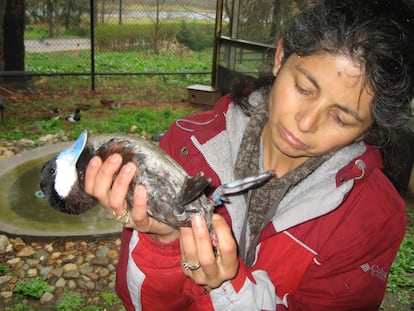

Biologist Patricia Brennan is a pioneer in the research of the sexuality of female species. Her discoveries range from ducks’ ‘anti-screw devices’ to a dolphin’s clitoris

When biologist Patricia Brennan first saw a duck penis, she says she nearly fell off her chair. It measured 20 centimeters – proportionally giant to its body – and was spiral-shaped. “It was like an enormous tentacle,” she remembers, laughing. “My immediate question was: And the female birds? Where does this horrible penis go?” No one had asked this before, despite the extensive knowledge that existed on the male duck penis.

The question opened a whole new field of investigation for the Colombia-born researcher. While many scientists had studied animal penises, almost nobody was interested in vaginas. That very same day, Brennan traveled to a farm near Sheffield University in England, where she was completing her postdoctoral investigation, and bought two female ducks so she could dissect them and study their vaginas. It was the beginning of a small revolution.

“It was one of those incredible moments where you say to yourself, ‘Wow, I can’t believe what I’m seeing’,” she tells EL PAÍS via a video call. “The vagina felt very thick, very strange and when this structure appeared I couldn’t believe it. How could it be that no one had seen it and described this?” Instead of a simple tube for a vagina, a female duck has a large, fibrous and labyrinthine anatomy. Brennan’s boss couldn’t believe the results. After proving that it wasn’t just an abnormality in a particular specimen, they reached out to the leading bird expert in France. He also said that he had never seen anything like it before.

Ducks are among the 3% of bird species that use a penis to copulate, the rest use a maneuver known as the “cloacal kiss,” in which a male bird transfers sperm by pressing its genital opening with the female’s. As a result, most bird experts had only ever studied the oviduct.

Brennan’s finding was important because it helped explain the strange shape of the duck penis. When a male duck does not have a partner, it violently forces itself on a female duck, sometimes as part of a group. “[Female ducks] suffer enormously during the sexual assaults, even dying,” explains Brennan, who is an assistant professor of biological sciences at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts. In response to this aggression, female ducks have evolved labyrinthine vaginas to prevent male ducks from fertilizing their eggs. In other words, they are fighting for control over their reproductive autonomy. “It’s incredible, it’s a very feminist story,” says Brennan. “At the end of the day, the females are winning the battle, they evolved an adaptation which gives the majority of paternity to the male that they have chosen.”

By contracting the vaginal muscles, the female duck is able to expel sperm. The result is that in duck species that have fewer cases of rape, the male has a smaller penis, as the female has not had to adapt its sexual organs to maintain its reproductive control.

A recent study of Australopithecus ramidus, an early hominid species, found that males had smaller teeth as females chose less violent partners. This perception of females as active agents in reproduction, capable of choosing their partner and even molding their very species, shocked the science world to its core. Especially given the legacy of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, which has led to today’s understanding of sex selection as two machos fighting to the death.

“This was a very disquieting topic in the age of Darwin and it also seems that way to many today,” explains Brennan. As Richard Prum, an evolutionary biologist at Yale University, who worked with Brennan explains in his book The Evolution of Beauty: “[Brennan’s] observations confirmed that the clockwise spirals of the duck vagina literally function as an anti-screw device.”

The form of male genitalia has been studied within the framework of the lock-and-key hypothesis i.e. if a penis – the key – was shaped in a certain way, it was because the vagina – the lock – was perfectly designed for it. But Brennan showed that females develop locks to keep out the keys, not the other way round.

“There was an incredible gap in our understanding of female species, of vaginas,” explains Brennan. “There has been a fascination with penises for a long time. Many scientists have studied penises, which are very interesting, but the problem is that there are hypotheses like the lock-and-key hypothesis. And most people who have examined this hypothesis have only looked at the male, the key.”

Dolphin research

Brennan’s latest finding is that dolphins have a clitoris that generates as much pleasure as a woman’s clitoris – and that it has another purpose. Female dolphins have a series of inner flaps and folds within the vagina, and it was thought that these were designed to keep out saltwater and protect male sperm. But Brennan’s research collaborator, Dara Orbach, discovered that there was great variation between dolphin species: some had one, while others had 15.

“Why was there so much variation if it was just to keep out saltwater? We decided to investigate this question and the result for me was incredible: we found basically the same thing in dolphins that we did in ducks,” explains Brennan. “A mechanism where the females are blocking access to the male penis: if it’s not located in the exact position or does not go inside, the sperm does not arrive.”

Although dolphins are often considered playful and childlike, male dolphins also have a violent side and are known to force copulation on females. But that is just one side of dolphins’ very complex sex life. The species also has sex for pleasure to socialize, often with members of the same sex, and also masturbate among one another.

Brennan is now a world-renowned specialist in animal vaginas, and is hoping to open an Institute of Vagina Research to fill the systematic gaps in the understanding of female biology. She believes her research can also help women: “If we understand a bit better the different design routes of vaginas in nature, that would help prevent problems in humans.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.