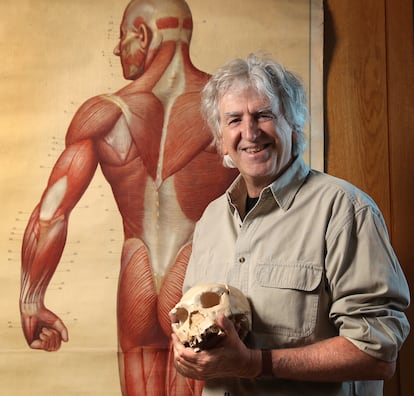

Juan Luis Arsuaga: ‘The human mind is a permanent aberration’

In his new book the paleoanthropologist and co-director of the Atapuerca Foundation describes the origin of the human body, which has determined what we are as a species

Paleoanthropologist Juan Luis Arsuaga says that our brain feeds on glucose and stories. And he is a storyteller par excellence. To begin with, he explains that he is in this world thanks to the Real Madrid soccer team. His father, Pedro María Arsuaga, played on the team as a left winger in the late 1940s. He was injured and sent to the stands to watch the games. There he noticed a young woman who would always sit next to him. The soccer player knew that his career would be short, so he enrolled in economics at Complutense University. One day, as he was going to class in the streetcar, he met that same girl, who was studying arts and philosophy. They talked, they liked each other and Juan Luis was the result.

The story comes to mind because Juan Luis Arsuaga’s mother took him to the Prado Museum a lot. Unlike most visitors, they always started with the Greek and Roman sculptures. Now, many years later, Arsuaga has used the shapes of some of the statues exhibited at the Madrid museum to structure Nuestro cuerpo (or Our body), a book in which he explores why, thanks to seven million years of evolution, we Homo sapiens look the way we do. His mother, Arsuaga says, is still very much a Real Madrid fan at age 94.

Question: What led you to write this book?

Answer: There are plenty of anatomy manuals with lots of illustrations, but why do we need them if we have our own body? Better yet, feel it [he starts elbowing the table and touching his arms, his back]. These are the epicondyles, the flexor and extensor muscles, the acromion. Or best of all, touch each other’s. It is much better in pairs.

Q. We are the only human species left on the planet. Why is our body so different?

A. We are the only ones because we have not left anyone else. We do not allow others. We are on the verge of wiping out our relatives, the chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans. We are ganging up on our relatives.

Q. Did we also wipe out the Neanderthals?

A. Without a doubt. Not in a war, but through competition.

Q. Is there anything that can wipe us out as a species?

A. The species, no. Civilization, maybe. There may be terrible calamities and bloodshed. When people get apocalyptic they say: “We’re going to wipe out the planet.” But no one can wipe out the planet. It can do more than we can. Life will go on and evolution will continue. It is we as a civilization who are in danger. You don’t need the apocalypse to be worried. In fact, the apocalyptic narrative is bullshit, because it solves nothing.

Q. The apocalypse is a biblical account. Is there room for God in your book?

A. I am not a believer. However, the religious phenomenon is fascinating. As Jacques Monod’s book Chance and Necessity says in the final sentence: “We now know that we are alone in an indifferent universe.” That’s the worst part. We are not in a cruel or hostile universe, but we are in an indifferent universe into which we have emerged by chance. Now we know, and we can choose what we want to be. There is no scientist who believes in a god who intervenes in human affairs. But there are many people, such as Baruch Espinoza, who have a transcendent idea. Something that represents the totality of the world, of the universe. The dream is to become one with him. I don’t believe in this either. I am an Epicurean. My idea is materialism and the pursuit of happiness.

Q. And where do you look for it?

A. One of the most important things now is to prove my theory about our body. From the head down it has the appearance of Homo erectus, and we are basically like them. Neanderthals evolved, became very wide and strong for climatic and ecological reasons. Instead, our body would be the primitive model. A narrow body like ours is very good for endurance running, for a marathon, for a species that travels long distances, that has a very wide territory. To give you an idea, the Hadza people of Lake Eyasi [in northern Tanzania], who are the last hunter-gatherers, travel the same distance in a year as from east to west in the United States: some 4,500 kilometers [2,796 miles]. It seems a lot. But think of the Camino de Santiago (pilgrimage trail). From Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port (France) to Santiago [de Compostela, Spain] it’s just over 700 kilometers [435 miles]. And we can usually do it within a month. It’s not so much. We are made for that and for long-distance races. We are an incredible machine, so it is almost impossible to lose weight.

Q. Why?

A. We are too efficient. Running consumes one calorie, or kilocalorie, per kilometer and kilogram of weight. You, who must weigh about 70 kilos [154 lbs], would expend 70 calories running one kilometer. If you run a distance of, say, five kilometers, you expend 350 calories. Nothing compared to what you put into your body with pancakes and cream. People think we are badly made, but the problem is that we don’t use up our fuel. So, try not to eat, because you won’t get rid of it.

Q. Since when did we get so efficient?

A. The other model, that of the Neanderthals, is for explosive stresses. We do not yet know what type of muscle fibers they had, we will know soon, but we assume they were fast twitch. Nearly every scientist says that those who were specialized were the Neanderthals and we are the primitive ones. I say it’s the other way around. It is like Copernicus. One of the two is very wrong. Either the Earth revolves around the Sun or the other way around. I am going to prove I am right by using fossils.

Q. Does our body give us a distinct advantage?

A. Biomechanically it is very good. The problem is that you had to be very strong to survive out there. We were very strong until the Neanderthals came along. We substituted the strength of the individual for the strength of the group. We became long-distance walkers because we established social networks, we exploited different resources, we built alliances, our biology is social. Also because we killed from a distance, with missiles or traps or by exhaustion. If you have to kill in a physical fight, you have to be very strong. But if you have a social system, you don’t. There are Eskimos who hunt without guns. The whole group chases the reindeer herd, cornering them and forcing them off a cliff. It’s all about intelligence, organization, and control of the territory. And controling territory comes from having a network of informants and alliances. This is also the origin of art and symbolic objects. Because if you wander around, how do you know that another group is of your ethnicity? Your identity objects will allow you to identify them. From this concept of body size comes everything else that makes us unique.

Q. Are we made for a life we no longer lead?

A. The problem is that we have to rediscover our sensations. Most of the time we don’t know we have a body. We don’t get cold because we wear coats, we don’t get hot because we have air conditioning. We go to the beach and take a chair with us. The first thing is to feel the body, and that is the reason for this book. Now, modern neuroscience has reversed the terms and says that it is not that the mind has a body, but that the body has a mind. The owner of the self is the body.

Q. In your book you say that beauty is only human?

A. Only we sapiens have it. Animals have no sense of aesthetics. They only value beauty in their own species. A robin likes the red color of another robin’s breast, but the yellow of the oriole is of no concern to him. For us, on the other hand, the oriole is as beautiful as a peacock, a leopard, the moon or a rainbow. And I believe that we are also unique in that respect.

Q. And did Neanderthals or other human species appreciate beauty?

A. I find it hard to believe, because it is nonsense, an aberration. All the things that seem normal to us in our species are delusional. The flag, a colored rag, or the cross and the crescent, for which we are capable of killing each other. The delirium that people experience at a soccer game. The human mind is a permanent aberration. There is nothing logical, there is nothing practical. And yet that’s where Mozart, Shakespeare, and Cervantes come from.

Q. You were talking about the end of civilization. Do you share some experts’ fear of artificial intelligence?

A. I listen to what people say with respect, but I don’t believe everything at the moment. And I wish artificial intelligence was a threat because that would mean it’s a very powerful technology. To be stronger than us it has to be amazing. And if it is very powerful, then it will be like any other technology, which have good and bad uses. Evolution has made us more empathetic than our ancestors, more sociable, more cooperative, more caring. Why shouldn’t a computer be not only more intelligent, but also more empathetic and generous than us?

Q. Do you plan to retire?

A. As a scientist, never. I’m only just getting started! I have researched, I have excavated, I have taught, I have written books, but I have never worked. I have enjoyed life and plan to continue to do so.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.