Don Neto and the Sinaloa old guard who reinvented drug trafficking in Guadalajara

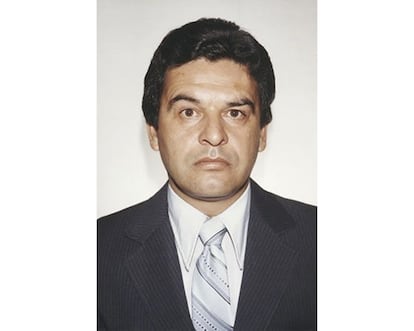

Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo, free after serving a 40-year sentence, went from marijuana smuggler to cocaine trafficker with the help of Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo and Rafael Caro Quintero, until their downfall after the murder of DEA agent Kiki Camarena

Don Neto called his room in Guadalupe Victoria prison, a penitentiary surrounded by a plain of farmland halfway between Durango and Torreón, “the forgotten cell.” In 2011, after two decades in the Altiplano prison, the health problems that afflicted him at 81 years of age precipitated his transfer. The aging Sinaloa drug lord thought his days of starvation, eating a pittance of cactus every morning for breakfast, and not getting medication for his numerous ailments were behind him. His calculations were wrong, and the warden of his new home forbade him from going out into the yard for fear of being attacked by other inmates. His daughter Esther protested: “Since he arrived, he doesn’t know if it’s day or night, because he remains immersed in darkness. They don’t even let him read the Bible.”

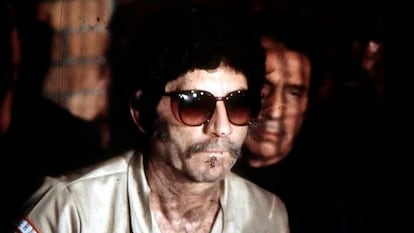

Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo always displayed old-school discretion. He let his partners, Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo “the Boss of Bosses” and Rafael Caro Quintero, “the Narco of Narcos,” co-founders of the Guadalajara Cartel, the Sinaloans who rewrote the rules of drug smuggling, hog the spotlight. During his four decades in prison, he hasn’t spoken a word. Last Saturday, having served his entire sentence, he regained his freedom for the first time since April 1985. Then, his final minutes as a free man were spent in a mansion on the Puerto Vallarta coast, owned by the head of security in the Jalisco city of Ameca. It was already obvious that his days were numbered, and he retreated to the Pacific to say goodbye. There, the army arrested him for the kidnapping and murder of DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena and Mexican pilot Alfredo Zavala. Freedom has found him again at the age of 95, in another luxury home, this time many miles from the sea, on a hill in Atizapán de Zaragoza, in the State of Mexico.

The little that is known about Don Neto’s life comes from his daughters and police investigations. His daughter Esther was interviewed by Ricardo Ravelo in 2011 for the magazine Proceso, shortly after he had secured a transfer to Guadalupe. That year, he was sentenced to 40 years after 26 years of incarceration without a conviction. By then, the drug lord was already an ailing old man begging the Mexican government for mercy. Esther complained to Ravelo about her father’s poor health and how the prison wouldn’t allow him to go out for surgery. She said he was a “very hard-working and responsible” man, that he denied killing Camarena — and she believed him — and that he was just a rancher whom the prison system had deprived of even the most worldly pleasures.

A decade ago, Julio Scherer crossed paths with Fonseca Carrillo in the Altiplano. “Don Neto, the oldest inmate and the oldest man in Almoloya, offers the image of a man who is leaving. His dull eyes resemble his listless voice. He looks at me, and I don’t know if he’s looking at me,” the dean of Mexican journalism later wrote. Scherer, who was in the prison interviewing some of its most notorious inmates for his book Maximum Security (2001), asked him to talk. Don Neto responded, monosyllabically:

— No.

Scherer got a lucky break. The Sinaloa drug lord refused, but he found his daughter, Ofelia, also locked up for drug trafficking. She told him about an absent father who, during her years of freedom, she saw once or twice a year, “on vacation.” They had more contact when Fonseca Carrillo was imprisoned in Altiplano. “I would tell him, laughing, ‘Now you can’t tell me you’re not here or that you’re busy or that you don’t want to see me.’ He would tell me, laughing too: ‘Now you can come whenever you want,’” Ofelia recalled.

In both interviews, 10 years apart, the two women portrayed a reserved, distant, and unloving man — ”Now that I’m here, the last time I saw him, all he gave me was a hug without the slightest affection,” Ofelia said, resigned. She didn’t even complain. She didn’t like to talk about her life, and at most, occasionally, she’d let slip an anecdote from her youth in the mountains of Sinaloa. Ravelo asked Esther:

— Has your father spoken to you about death?

— No, he hardly ever talks about it.

Veteran before the Guadalajara Cartel

Esther denied that the family was wealthy — “our life is modest” — and claimed they hadn’t inherited the fortune their father amassed during his years as a drug lord. In 2016, Fonseca Carrillo was transferred to the home of one of his brothers to serve out his sentence under house arrest, in a luxury residence in a residential neighborhood in Atizapán where the average price of a property exceeds $1 million.

Half an hour from Mexico City, you can spot it from afar: among bare hills, the Hacienda de Valle Escondido is dotted with trees as a status symbol. It’s one of those neighborhoods with security at the gate, where any visitor is considered suspect until proven otherwise, and without an invitation from its residents, you aren’t allowed in. Don Neto’s house is under federal guard.

Fonseca Carrillo was born in 1930 in Santiago de los Caballeros, a mountain town in the municipality of Badiraguato, with a larger population in the cemetery than above ground. Badiraguato witnessed the birth of the generation of smugglers who would change the rules of the business and cement the laws of modern drug trafficking: in addition to Don Neto and Caro Quintero, Juan José Esparragoza “El Azul,” Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, and the Beltrán Leyva brothers. The Sinaloa drug trafficking family tree has short branches: Fonseca Carrillo is also the uncle of Amado and Vicente Carrillo, Sinaloans who would later become leaders of the Juárez Cartel. Some versions say it was Don Neto who sent them north to take over the organization.

In the Golden Triangle — the mountains of Sinaloa, Durango, and Chihuahua — marijuana and poppy cultivation have always existed. They provided the livelihood of many ranches. And where there are crops, there is smuggling. At 20, Don Neto was already making his way in the rudimentary business as the right-hand man of Pedro Avilés, “The Lion of the Sierra.” With the ravages of Operation Condor, which led the army to burn entire crops and imprison farmers, the younger smugglers moved to Guadalajara. There, Don Neto, Caro Quintero, and Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo would found what history knows as the Guadalajara Cartel.

They modernized their processes, established ties with Colombian cartels to transport their cocaine from South America to the United States, diversified their investments, and became respectable businessmen. They left the ranch behind and crashed the private party of the Guadalajara bourgeoisie. For a few years, their alliances with high-profile politicians and police officers made them untouchable. The DEA, however, was on their trail.

An agent, Kiki Camarena, infiltrated the organization. He discovered El Búfalo, a ranch spanning thousands of acres in the middle of the Chihuahuan Desert planted with 8,000 tons of a new type of marijuana. The Mexican authorities knew: it was impossible for a crop of that size to go undetected, but cartel bribes lubricated the state machinery. With the help of pilot Alfredo Zavala, Camarena photographed the plantation from the air. Faced with the evidence, captured by a foreign agent, the government had to intervene. The army burned the entire marijuana crop in November 1984.

Less than four months later, the Guadalajara Cartel kidnapped Camarena and Zavala. They were brutally tortured and mutilated for weeks. A doctor kept them alive to prolong the interrogation. A month later, their bodies were dumped in a ditch around 100 miles from Guadalajara. It was the final nail in the coffin. First, Caro Quintero, whom the DEA considered the mastermind, was arrested in April 1985. A few days later, Don Neto. Finally, in 1989, Félix Gallardo. The organization splintered, and others, such as the Sinaloa Cartel, emerged from its ranks.

Don Neto was 55 at the time, much older than his companions. He was already a veteran when they joined forces. When he was first arrested in Mexicali in 1955 for trafficking opium gum, Félix Gallardo hadn’t even turned 10, and Caro Quintero was around three. Now, he’s the only one of the three at liberty. Félix Gallardo, wheelchair-bound, nearly deaf, and blind in one eye, will complete his sentence in 2029 in Mexico. Caro Quintero, extradited to the United States, spends his days in a Brooklyn prison, uncertain whether the Prosecutor’s Office will seek the death penalty.

Although President Claudia Sheinbaum assured that there is no extradition order against Fonseca Carrillo, the DEA still has him on its fugitive list. His file, over a grainy, opaque black-and-white photograph, reads: “Armed and dangerous.” It seems a bit outdated. Don Neto, today, is a mass of illnesses: blind, deaf, a survivor of several heart attacks, among a host of other ailments. One wonders if his luxurious residence still has the Bible he was denied in prison. A huge mausoleum he commissioned has been waiting for him for years in the Santiago de los Caballeros cemetery: a copy of the Parthenon in Athens, in a village in the Golden Triangle.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.