Why are we the only human species left on the planet?

Three recent discoveries have led scientists to re-evaluate the origins of ‘Homo sapiens’ and our evolutionary history

Three discoveries have changed what we know about the origin of the human race and of our own species, Homo sapiens. It is possible, according to some experts, that we may have to rethink this concept when it comes to referring to ourselves as these new discoveries suggest that we may be a type of Frankenstein hybrid made up of pieces of other human species, with whom until relatively recently we shared our planet and produced offspring.

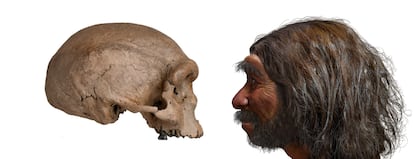

The finds made last week point to there having been up to eight different species or groups of humans in existence 200,000 years ago. All of these form part of the Homo assignation, in which modern humans are included. The recent additions to human evolution display an interesting blend of primitive characteristics – huge arches above the eyebrows and flat heads – as well as modern ones. The so-called “Dragon Man” or Homo longi discovered in China” possessed a cranial capacity similar to or greater than modern humans. The Nesher Ramla Homo, discovered in Israel, could possibly be from a species that preceded and contributed to the European Neanderthals and East Asian Denisovans, with whom our own species had repeated sexual encounters producing mixed-race children who were accepted by their tribes as another member of the family.

Today we know that because of this intermingling every modern human beyond the African continent carries 3% Neanderthal DNA and that the inhabitants of Tibet carry genes that enable them to live at high altitudes that were passed on from the Denisovans. Genetic analysis of the current population of New Guinea suggests that the Denisovans – a branch of the Neanderthal family tree – remained in existence as recently as 15,000 years ago, a mere blink of the eye in evolutionary terms.

The third big discovery made in the last few days could have been on an episode of a detective show. Researchers analyzed DNA preserved in the floor of the Denisova cave in Siberia and found genetic material from indigenous humans, Denisovans, Neanderthals and Homo sapiens dating from periods of such close proximity that they all could have overlapped. Three years ago, the remains of the first known hybrid of two human species were discovered in the same place: the daughter of a Neanderthal and a Denisovan.

Paleoanthropologist Florent Detroit gave science one of these new human species when he identified Homo luzonensis, who lived on an island in the Philippines 67,000 years ago and had a curious mixture of characteristics that could have been the result of a long evolution of over a million years, spent without contact with other early humans. It is a similar story to that of his contemporary, Homo floresiensis, or Flores Man, a human species standing just a meter and a half tall who lived on the Indonesian island. Flores Man had a brain the same size as a chimpanzee but if we apply the intelligence test most commonly used by paleoanthropologists, we can say that he was as advanced as sapiens and used stone tools of equal evolutionary craftsmanship.

To these two island dwellers can be added Homo erectus, the first human traveler who departed Africa two million years ago, spreading throughout Asia and who existed there until fewer than 100,000 years ago. The eighth player in this story is Homo daliensis, whose fossilized remains were found in China and who was a mixture of erectus and sapiens, although daliensis may yet be ascribed to the recently denominated line of Homo longi.

“It does not surprise me that there were various species of humans alive at the same time,” says Detroit. “If we take into account the last geologic age, which started 2.5 million years ago, there have always been different races and species of hominoids sharing the planet. The big exception is the present day: never before has one human species existed alone on the earth.”

Why are sapiens the last humans standing? For Juan Luis Arsuaga, a paleoanthropologist working at the Atapuerca archeological site in northern Spain, the answer is community. “We are a hyper-social species, the only ones capable of constructing bonds beyond kinship, unlike the rest of the mammals. We share consensual stories like country, religion, language, football teams; and we are willing to sacrifice many things for them.” Not even the Neanderthals, our closest relatives, who fashioned ornaments, symbols and art, shared this behavior. “The Neanderthals did not have a flag,” notes Arsuaga. For reasons that are still unknown, the Neanderthals died out some 40,000 years ago.

Sapiens were not “superior in the strictest sense” to their contemporaries, says Antonio Rosas of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC). “Today we know that we are the result of hybridizations with other species and the combination of characteristics that we possess turned out to be perfect for that moment in time.” Another possible additional advantage is that Homo sapiens lived in more numerous groups than the Neanderthals, which would lead to less inbreeding and better general health among populations.

Detroit believes that part of the explanation lies in the very essence of sapiens, which means wise in Latin. “We have a huge brain that we need to nourish, as such we need many resources and as a result a lot of territory. Homo sapiens experienced a vast demographic expansion and it is very likely that competition for territory was too hard for the rest of the species,” says Detroit.

María Martinón-Torres, director of the Spanish National Center for Research on Human Evolution, believes that the secret to Homo sapiens’ success is “hyper adaptability.” “Ours is an invasive species and while not necessarily ill-intentioned, we have been an evolutionary Attila the Hun,” Martinón-Torres says. “At our pace and due to our way of life biological diversity has been diminished, including that of humans. We are one of the most impactful ecological forces on the planet and this history, our history, started to be forged in the Pleistocene [the geological period from 2.5 million years ago to 10,000 years ago, when Homo sapiens were the only remaining human species in existence].

The recent finds have served to add fuel to a growing issue: scientists are naming more and more human species, but is it logical to do so? In the view of Israel Hershkovitz, an Israeli paleoanthropologist who made the discovery at the Nesher Ramla archaeological site, the answer is no. “There are too many species,” he says. “The classical definition states that two different species cannot have fertile children. DNA tells us that Homo sapiens, Neanderthals and Denisovans had such children, in which case they should be considered the same species.”

“If we are sapiens, then these species who are our ancestors by way of admixture are also sapiens,” notes João Zilhão, a Barcelona University professor at the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies.

This issue has become a source of confrontation between experts. José María Bermúdez de Castro, co-director of the Atapuerca site, points out that “hybridization is very common among existing species, especially in the vegetable world. The concept of species can be nuanced, but I don’t think we should abandon it because it is very useful for helping us to understand.”

There are many factors at play in this debate. The evident differences between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals are not the same thing as the identity of a species such as Homo luzonensis, of whom only a few teeth and bones have ever been discovered, or the Denisovans, of whom the majority of available information derives from DNA extracted from tiny fossils.

“Curiously, despite the frequent contact between them, Homo sapiens and Neanderthals have been perfectly recognizable and distinguishable species until the end,” says Martinón-Torres. “The traits of the late Neanderthals are more marked than their predecessors, rather than having become less distinct as a result of mixing. There were biological interchanges, and possibly cultural ones, but neither of these species stopped being themselves: distinct, biologically and visually identifiable, with their specific adaptations and their ecological niche in the history of evolution. I believe this is the best example that hybridization does not necessarily collide with the concept of species.”

Martinón-Torres’ colleague, Hershkovitz, believes the debate will continue though: “We are excavating at another three caves in Israel where we have found human fossils that will lend a new perspective to human evolution,” he says.

English version by Rob Train.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.