The first great European war took place in the north of the Iberian Peninsula over 5,000 years ago

A quarter of the hundreds of remains from a mass burial in Álava, Spain, have wounds caused by clubs, arrows or stones

In 1985, while working to widen a road near Laguardia in Álava, Spain, a digger uncovered a massive burial site. There were thousands of bones that took some time to sort out. The remains were crowded, mixed and placed in unnatural positions. Those who first studied them maintained that it was a mass grave into which the victims of a massacre had been thrown. At the time, the idea of large-scale conflicts in the Neolithic era thousands of years ago was not widely accepted among archaeologists and prehistorians. Now, an examination with current forensic techniques points in another direction: those buried at the site died in what could have been Europe’s first great war.

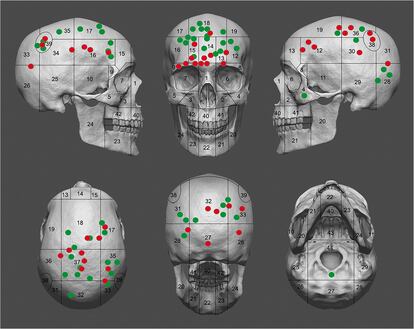

There, in front of the hermitage of San Juan Ante Portam Latinam, researchers eventually counted 338 bodies. While there are women and children, most are men, especially young men. Dated through the radiocarbon dating technique, researchers found that the bodies were dumped there between 5,000 and 5,400 years ago, at the end of Europe’s Neolithic period. The results of that research were published in Scientific Reports, and they show that a quarter of the remains have fractures in their skulls or, more specifically, holes resulting from a strong blow with a blunt object. Most of those with these cranial traumas are young and adult men, and many of them sustained several injuries. In some cases, the bone shows signs of healing, evidence that those people survived their injuries. But half of the marks reflected wounds that had not healed.

Researcher Teresa Fernández of the University of Valladolid, Spain, the article’s lead author, studies past violence based on osteoarchaeology, the study of prehistoric bones. “In San Juan Ante Portam Latinam we found many unhealed wounds, that is, [they were] perimortem. It may have been a spleen wound that killed them, but they died without their head wounds having healed,” says Fernández. This is one of the work’s key elements. When the first studies of the site were conducted last century, the remains with cranial trauma were observed “but only those without scarring,” the researcher notes. Since then, several burials of violent origin have been discovered in various parts of the world, especially in Europe, fueling the study of prehistoric violence. Thus, the researchers decided to reanalyze the bodies using modern forensic techniques.

They found that 78 of the bodies dumped there (it was not a burial as such) had cranial wounds, almost half of which were unhealed, indicating that they died when they were wounded or shortly thereafter. But the archaeologist points out that “there must have been more violent deaths.” A mortal wound in the heart would leave its mark in the ribs or sternum, but wounds to the liver or kidneys, also vital organs, or to the intestines, would not leave any trace, and they would cause the victim to die of exsanguination (that is, they would bleed to death). At the site, researchers found dozens of flint blades that served as daggers, as well as axes and other bone weapons that could belong to the people buried there. In this part of the world, metallurgy had not yet been discovered, so the arms were all made of stone and bone. But there were also about fifty arrowheads discovered at the site. Although researchers have not been able to analyze all of them in detail, most show wear in their contours, indicating that they were used. In addition, they were found intermingled with the bones. And finally, there are about ten notches in skulls and bones that fit the arrows exactly. That is, they were enemy arrows stuck in the bodies. Overall, there is no other prehistoric site in Europe that has so many injuries caused by arrows. “In general, it is estimated that up to 50% of violent deaths do not leave a mark on the bones,” recalls Fernández.

It is estimated that up to 50% of violent deaths do not leave a mark on the bones.Archaeologist Teresa Fernández of the University of Valladolid

An arrow mark was first discovered at San Juan Ante Portam Latinam in 1999, in fieldwork led by Francisco Etxeberria, a forensic anthropologist at the University of the Basque Country. “At the time, most prehistorians jumped all over us. But we kept seeing more cases, and it was clear that this site was atypical and was the greatest evidence of prehistorical violence,” he says. Etxeberria has also participated in some of the best-known recent autopsies, including those of Lasa and Zabala, Pablo Neruda, the children of convicted Spanish killer José Bretón and several mass graves from the Spanish Civil War. “At least we managed to do that. Since then, they began to think that the arrowheads found in other burials were not offerings or grave goods, but rather what killed them,” Etxeberria states. That was precisely what led them to review their own work in San Juan Ante Portan Latinam almost 25 years earlier.

“The first thing to keep in mind is that a broken bone is not the same as one fractured by a traumatic injury in fresh tissue that leaves a mark,” says Etxeberria, who has relied on the forensic anthropology of court cases to try to figure out how those people died. “It is not a dolmen or a cave. It is as if they had been buried hastily. [Was it] all on the same day? We don’t know, but they are from a continuous conflict,” Etxeberria explains. Unfortunately, radiocarbon dating has not allowed the researchers to narrow down the time frame, so there’s nothing to prevent us from thinking that they all died in a single battle, but we cannot rule out that they died in successive battles “over months [or] at most years,” his colleague Fernández says.

It is as if they were buried hastily. [Was it] all on the same day? We don’t know, but they are from a continuous conflictForensic anthropologist Francisco Etxeberria of the University of the Basque Country

The details reinforce the idea of war. Although many of the wounds were caused by arrows fired from a distance or by flint daggers, perhaps from a spear, “several of the head traumas have a characteristically round pattern, with a caved-in skull,” says Etxeberria. From his forensic practice, he is well-versed in distinguishing the marks that different objects leave. “It is not the mark of a hammer; instead, it could be the mark of a club [like the ones found at the site] or of stones,” he adds. Most of the cranial traumas are in the lateral and frontal parts of the head, almost always above what forensic scientists call the hat brim line (HBL), so they must have been caused in a direct melee fight. But half of the side blows were to the right side of the head. So, half of the attackers were either left-handed or came at the victims from behind. All the clues point to one or more battles to the death involving dozens, perhaps hundreds of combatants.

Until now, experts had believed that the first major war, or rather the first great battle, took place some 3,275 years ago on the banks of the river that runs through the Tollense valley in the present-day state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania in Germany. That places the battle at the beginning of the European Bronze Age. The events at San Juan Ante Portam Latinam occurred almost 2,000 years earlier. Hundreds of bodies have already been unearthed at the German site, although it is believed that there could be over 1,000 in total.

There is still a lot that remains unknown about the Álava burial. One mystery is the presence of children and women, some of whom bear the marks of a violent death. Researchers do not have all the necessary information to explain their presence at the site. Fernández mentions one possibility: “Here we have many more adolescents than in Tollense, which could be because the previous battles decimated the adult males and they had to be replaced. If they had to resort to teenagers, why not women as well?”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.