Notches in the teeth of ‘seamstresses’ show how work was divided by sex 5,000 years ago

A study by the universities of Valladolid, Murcia, and Burgos reveals ‘the earliest evidence of craft specialization in the Iberian Peninsula’

In December 2007, during construction work on some houses in Caravaca in Murcia (Spain), the site known as Camino del Molino was found by chance. It was a mass grave of 1,348 individuals and 52 dogs, dating from the 3rd millennium B.C. and used for about four centuries, and was hidden inside a cavity about seven meters in diameter. About 400 meters away was the Chalcolithic town of Molinos de Papel, from which the bodies are supposed to have come. The archaeologists in Camino del Molino found hardly any grave goods, beyond a few dozen ceramic vessels, 30 arrowheads, a dagger, various necklace beads and 17 punches. However, this scarcity of material has not prevented experts from making notable progress in understanding the society from 5,000 years ago and in how men and women shared community roles. How did they do that? By analyzing the human remains; specifically, the teeth.

The study New insight into prehistoric craft specialisation. Tooth-tool use in the Chalcolithic burial site of Camino del Molino ― by Sonia Díaz-Navarro, Rebeca García-González, Nico Cirotto, and María Haber Uriarte, from the universities of Valladolid, Burgos, and Murcia, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science ― details the results of analysis done on the the teeth of 102 individuals, of which eight ―seven women and one probable man― show “occlusal grooves [area where the teeth of the upper and lower jaw fit together] and interproximal grooves [between the teeth] consisting of fine parallel grooves, as well as labial notches and chipping of the enamel.”

The results suggest that these people “used their teeth as a third hand in artisan tasks, such as the processing of vegetable fibers for textile production, thus representing the earliest evidence of craft specialization in the Iberian Peninsula and potential proof of a possible division of work based on sex in a Chalcolithic community,” the study states. That is to say, “a possible specialization of the women in the Camino del Molino community in this economic activity from adolescence.” Other analyses corroborate this possible division of labor by sex, such as strontium isotopes or the morphometric analysis of the bones of this population, so everything seems to point to a specialization of men in livestock and grazing tasks and women in other cloth making activities.

The Iberian Copper Age is characterized by a significant investment in defensive architectural structures, the intensification of agricultural production, population growth, and political centralization. “These processes were accompanied by intense funerary activity, in which tombs of various kinds were built, both megalithic, natural caves, artificial caves, or hypogea [underground chambers]. Most of the Iberian funerary finds from the 3rd millennium B.C. are located near settlements and around the main riverbeds. In the southeast, cemeteries with collective tholos [circular] graves are the most common.”

The archaeologists recall that in the case of Camino del Molino, the burial is “characterized by the repeated interment of corpses, in many cases simultaneously, which were grouped around the walls of the structure as the central space was filled. In fact, some individuals from the peripheral areas have been recovered in perfect anatomical connection, while others, further inside the burial, have been found in the form of bone or dismembered packages.” All died before the age of 59 and the largest age group (38.2%) ranges from 21 to 39. Carbon-14 dating has identified two funerary phases in the tomb: between the years 2971 and 2711 B.C. and between 2451 and 2251 B.C.

To understand the magnitude of this tomb, it is necessary to investigate the funerary record of other contemporary sites. In Europe, although there are communal burials with a large number of individuals, such as the Crottes hypogeum, in Roaix, or the Boileau hypogeum, in Vaucluse (both in France), none comes close to the size of Camino del Molino, since they do not exceed 500 people.

The dental wear of the individuals that were analyzed ― generally elongated grooves, with V-shaped grooves and chipped enamel ― points to small threads, coming from fibers such as flax or hemp. Various experimental studies have shown that other materials, such as wicker, produce deeper and non-parallel grooves due to their relative hardness and irregularity. “Therefore, all the evidence seems to indicate that certain individuals [women] held some hard object, such as a needle, in their mouths, which caused the detachment of the enamel on the front-facing surface of the front teeth, while using the surfaces between the incisors and the chewing surfaces of the molars to repeatedly drag some type of fine plant tissue.”

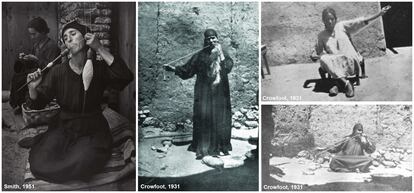

There are sources that confirm these practices in Prehistory and Antiquity, as demonstrated by the iconographic representations in Egyptian tombs from the 3rd millennium B.C. that represent young artisans working with thread, or the kylix of Orvieto (Etruscan vessel from 500 B.C.) representing a young woman spinning with her mouth. Mycenaean writings from the second millennium B.C. have also been found that allude to children working linen, carding, spinning, sewing, and weaving. In the Lengyel culture (Central European Neolithic between 5,000 and 7,000 years ago) women used their teeth to spin, and men used theirs to work leather. In modern times, girls were the ones who knew how to spin flax and comb wool, as the current populations of Akwete Igbo (Nigeria) or Nahya, and Kirdasseh (Egypt) do. In addition, this activity was carried out by Spanish and Portuguese women, using their teeth, until the end of the 20th century.

In short, the authors of the study conclude, “the dental wear of Camino del Molino is shown to be an excellent tool to identify the development of specific activities and thus delve into the social organization and complexity of populations from the 3rd millennium B.C.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.