Meta’s digital censorship targets art from the Leopold Museum in Vienna

According to the prestigious institution, the works of established artists such as Egon Schiele and Christian Schad have been blocked by Instagram and Facebook

In 2021, museums in Vienna launched a witty campaign to protest the censorship of art on social media: they opened an account on OnlyFans, a platform that monetizes pornographic content. That year, a short video featuring the 1914 painting Liebespaar by Koloman Moser — made to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the founding of the Leopold Museum — was rejected by Facebook and Instagram as “potentially pornographic.” Three years later, the Leopold Museum in Vienna has launched a new campaign against Meta, the parent company of Instagram and Facebook. This time it goes straight to the point: “Do you think this work of art should be censored?” it asks in a social media post featuring works by Egon Schiele and Christian Schad. “Meta does!”

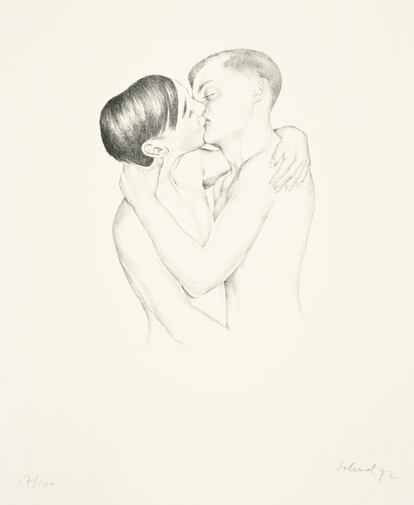

The work Liebespaar — which depicts two half-naked lovers embracing — has its own commemorative postage stamp. Schiele’s presence on the streets of Vienna can now be felt almost as keenly as Klimt’s. And Schad is one of the key figures of Splendor and Misery, the Leopold Museum’s latest exhibition dedicated to the New Objectivity in Germany, the interwar aesthetic movement that was killed by the rise of Nazism.

The Leopold Museum has used its own accounts on Instagram and Facebook to launch its crusade against Meta’s censorship. “Our images are repeatedly reported for sexually explicit content,” says the museum’s social media manager, Pia Semorad. “Most of the time, artworks with female nudity and homosexual content — not male nudity — are reported and undergo a review period of about 24 hours. In the process, the images are temporarily ‘blocked.’ They are not shared to non-followers or displayed on the Explore page. What’s more, our account is displayed lower in the feed to followers. In major cases, our account is restricted: its content is not shown to unfamiliar users and the account cannot be found by typing our name in the search bar. We have found that the same post can be reviewed various times, so there seems to be no limit.”

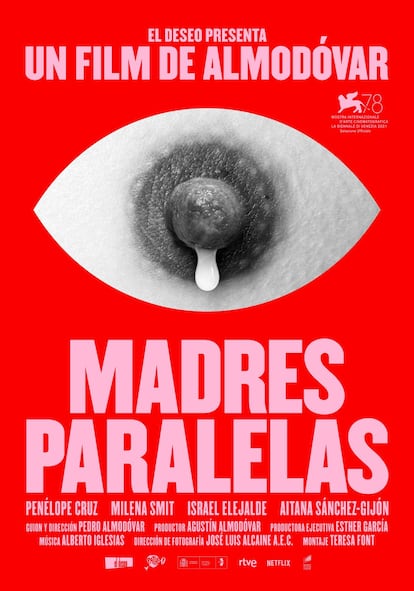

When asked about the Leopold Museum’s campaign, Meta refers to its community guidelines, which states that “nudity in photos of paintings and sculptures is OK.” However, the number of artists from the Leopold Museum that have been censored continues to grow. Along with Christian Schad and Egon Schiele, works by Oskar Kokoschka, Max Oppenheimer, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Anton Kolig, Max Kurzweil and Richard Gerstl have also been reported. In 2021, Instagram also banned the poster for Pedro Almodóvar’s film Parallel Mothers for considering it “erotic or pornographic content.” Designed by Javier Jaén, the poster shows a nipple with a drop of breast milk.

“The problem lies in the automated system used to detect and review the content,” says Pia Semorad. “Technology fails to distinguish between artistic nudity and real photographs, and images are constantly blocked, making our account unsearchable. This amounts to censorship on social media, even if we are not violating the rules.”

Meta has censored two reels from the latest exhibition at the Leopold Museum, in addition to Christian Schad’s works Loving Boys and Self-portrait with Model. It is ironic that one of the most prestigious museums in Europe hosts an exhibition like Splendor and Misery — which explores the search for sexual liberation, the recognition of same-sex relationships, the breaking of taboos and the “new woman” that emerged in the turbulent Berlin society of the 1920s, more than a hundred years ago — and is censored by a 21st century tech corporation.

Self-portrait with Model is an allegory of narcissism. It was painted by Schad in Vienna in 1927. Last Sunday a Japanese couple viewed the work with interest while their children ran around the room among canvases by George Grosz, Otto Dix, Karl Hofer and Karl Hubbuch, a specialist in homoerotic portraiture. The couple looked at the naked model’s facial scar. Schad added it after his experience in Naples, where men marked the faces of their lovers with a freggio scar, in a barbaric sign of ownership and as a warning to potential rivals.

Christian Schad also frequently depicted the new self-sufficient woman of the 1920s, who was later erased from the public scene by Nazism. This character is seen in his works Marcella (1926), Lola (1928) and Maika (1929), which are on display in the Splendor and Misery exhibition. It also includes the sophisticated illustrations of Jeanne Mammen and the so-called degenerate art — the label applied by the Nazi party — of the avant-garde painters Lotte Laserstein and Kate Diehn-Bitt.

Why does Instagram censor art? And why hasn’t Meta developed a technology to prevent this from happening? “Because large social media companies are American and are subject to their legislation, but also to their moral standards, which are more puritan than European standards,” says Delia Rodríguez, a writer who specializes in the relationship between technology, media and society. “As its business is also global, and many countries are even more conservative, it will always lean towards a restrictive lowest common denominator. There are frequent controversies because it is difficult to moderate so much content properly, you have to apply common sense and review each case in detail, and that is expensive.”

Digital censorship has dogged other museums in Vienna. In 2019, Instagram found that Helena Fourment in a Fur Robe — a 1638 oil painting by Rubens on display at the Museum of Art History — violated its community guidelines. A year earlier, a photograph of the Venus of Willendorf — a Paleolithic sculpture more than 29,500 years old that NHM Vienna calls “the most important object in our entire collection and one of the most famous archaeological finds in the world” — was blocked by Facebook. Meanwhile, the Albertina Museum in Vienna, came under attack from TikTok: the platform suspended its account for showing a work by Japanese photographer Nobuyoshi Araki in which a female breast was visible.

Amid the inconsistency in how social media companies applies their guidelines, there is an additional problem: the lack of transparency. “There must have been a recent change in how rules are implemented,” says Pia Semorad: “We did not have these persistent problems until the end of 2023, but we do not want to remove our works or give in to Meta’s restrictions. We also don’t know if our account is being classified in other negative ways that we are not aware of.”

Delia Rodriguez notes that “lately, tech companies are cutting investment in human moderation to focus on artificial intelligence, which is not very effective at weighing moral and cultural norms. Automatic moderation systems make many mistakes in distinguishing nuances such as what is art and what is porn.”

For now, Meta’s censorship policies are leaving digital scars on the Leopold Museum’s artworks.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.