Banning ‘Maus’: Erasing memories of the Holocaust

The recent censoring of Art Spiegelman’s acclaimed graphic novel only reinforces the moral value of his work

Nazism was defeated in May 1945, but anti-Semitism is alive and well. It’s not just limited to the rants of millenarian Reich revivalists or racist one-party ideologues. Recently, a US county school board in Tennessee banned the graphic novel Maus from its libraries and classrooms, citing its use of profanity and depictions of nudity. The American Library Association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom lists almost 500 publications that have been banned in the various parts of the US, including the award-winning novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, the Tintin comics, The Adventures of Captain Underpants, and the classic movie, Gone with the Wind. Paradoxically, this type of censorship is justified as being for the common good because, we are told, we need to be saved from the unnecessary pain of being exposed to “unacceptable ideas.”

But the censorship of a masterpiece like Maus has only reinforced its moral value. It has sold millions of copies worldwide, and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992. But perhaps its greatest value is in keeping the memory of the Holocaust alive for new generations to understand.

Art Spiegelman was born in Stockholm in 1948. Although his parents survived the Holocaust, his older brother, Richieu, did not. After his mother committed suicide in 1968, Spiegelman immersed himself in the thriving underground comic scene of the late 1960s. A few years later, Spiegelman joined forces with Bill Griffith to edit Arcade, a publication that featured veteran underground cartoonists like Robert Crumb and Gilbert Shelton. In 1980, Spiegelman and his wife, Françoise Mouly, founded Raw magazine, where graphic art came of age in a large-format comic book that featured a huge lineup of cartoonists such as Kaz, Gary Panter, Charles Burns, Sue Coe and many others.

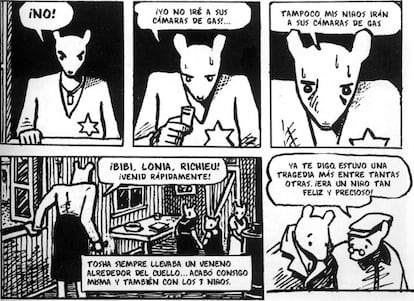

The first pages of Maus were published in 1972 in the underground comix, Funny Animals, edited by Spiegelman’s friend and future Raw co-editor, Justin Green. One of the great innovations of Maus is its use of anthropomorphic animals to represent the hell of the Nazi extermination and anti-Semitic persecution in Europe. Jews are depicted as little mice, the Nazis are cats, and the Polish collaborators are pigs in Spiegelman’s black-and-white Orwellian metaphor. Another striking feature of Maus is its use of analytical introspection. Like Crumb and Green, Spiegelman brilliantly uses the first person perspective to communicate deep and complex thoughts about the horrific Holocaust with great psychological realism.

There are two parallel stories in Maus that unfold in very different times, circumstances and places, but are united by the umbilical cord of a common heritage. His father, Vladeck, tells the story of the family’s life in Poland and their struggle to survive the extermination. In parallel, Maus is also a contemporary, autobiographical analysis of Jewish assimilation in the US during the last half of the 20th century. At one point in Maus, Vladeck cynically warns his son about friendship: “Lock yourself and your best friends in a room for a week with no food or water, and then see who your friends are!” The tremendously vivid stories of two very different times make it impossible for us to relegate the Holocaust to the dusty bookshelves of history.

Some of the first strips of what later became Maus appeared in Spiegelman’s Breakdowns: From Maus to Now, an Anthology of Strips (1977). Breakdowns, which can mean failures, interruptions, ruptures, collapses and mental illness, are everywhere in Maus. Life in the Jewish ghetto, Nazi collaboration and spying by neighbors, Auschwitz-bound trains, tattooed numbers on death camp prisoners, forced labor, systematic extermination of children, suicide, gas chambers and so many other terrible and inhuman episodes are expressed in the language of comics, enabling Spiegelman to go further and deeper than many emotionless histories and archival collections about the Shoah. It’s not that we don’t need such documents, it’s that they’re insufficient. We need Maus.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.