Can a voluptuous bustline become art? The myth and tragedy of women with extreme physiques

A book on the vedette Lolo Ferrari, star of the 1990s and owner of the then-largest breast prostheses in the world, revives a debate over radical body transformation and whether there’s any art in the practice

In December 2023, Sophie Anderson died at the age of 36. Anderson was a porn actress, activist, comedian and a social media celebrity (nearly 360,000 people followed her on X, previously known as Twitter, where adult film stars have more presence due to less censorship of nudity). She presented herself as pansexual, outspoken and proudly vulgar. But for some, the most recognizable thing about her was an extreme physique, with breasts that defied gravity and the standard rules governing human anatomy.

Her image was made more complex by the personality that Anderson showed online. She greeted her followers with a loving “guys, girlies and nonbinary friends” and her advocacy for equality and love of camp made her a kind of muse for a sector of the British LGBT community, who often invited her to Pride marches. Her profile in pornographic videos — staged, theatric, at times closer to slapstick comedy or to that of an adult comic book heroine than your classic porn actress geared towards male pleasure — placed her in a realm beyond that of adult entertainment. Bibles of modernity like Interview and Dazed photographed and interviewed her. It wasn’t the first time that a woman with an extreme, hypersexualized physique crossed a bridge to become a post-ironic icon, someone who could share space with artists, designers, and luxury brands.

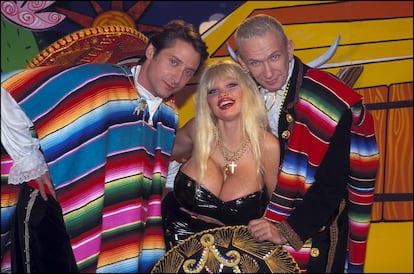

Anderson followed in the footsteps of other women who have worn disproportionately large implants that contributed to their fame. There’s an entire lineage of erotic actresses and models who, thanks to surgery, liposuction, dyes and makeup, approximate the look of a living blow-up doll. The French Lolo Ferrari (1963-2000) has been among the most famous, recognized in her day by the Guinness World Records as the woman with the largest breast implants in the world.

A posthumanist fantasy

In the Spanish language book Lolo (published by Niños Gratis) writer Miguel Agnes seeks to bring justice to a figure that was undervalued for years and seen as a dim-witted porn star. “The bimbo has always lived in our imagination, but Lolo Ferrari’s version took the concept a step further. She decided, likely induced by her husband, Eric Vigne, to make a surgical transition towards an inhuman silhouette. Lolo put her body on the surgeon’s table to sculpt in her own flesh a post-humanist fantasy, an unconscious archetype that until then, had only been glimpsed via the bodies of transsexual women in the underground.”

There have been other Lolos. Argentine Sabrina Sabrok (Buenos Aires, 53 years old) was recognized in 2006 and 2009 by Guinness as the women with the largest breast implants in the world. In 2020, she told an interviewer that they weighed 11 pounds apiece. Pandora Peaks was the last muse of Russ Meyer, who was famous in the 1970s for creating a series of films that, for some, represented heteronormative paradises, filled with women sporting enormous breasts. For others, they were the height of psychedelia, irony and humor. Porn and eroticism serve as a natural environment for this type of bodies, which are perfected and brought to extremes by cosmetic surgery, although Agnes writes that in reality, Ferrari only filmed a single pornographic film “which the industry dissected and shared in a multitude of compilations, giving the impression that it was her primary activity. The stigma stuck, and Lolo always regretted it. Apparently, she had done it under pressure from her manager and husband.”

The stigma of the sexual object is not entirely correct, according to Tania Pardo, deputy director of the Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo. To her, these kinds of bodies represent “a hypersexualized conception of women, but there’s something in that extreme that can be understood as a revindication of excess. I think about transvestism and the construction of diverse identities through hypersexualized aesthetics yet, on the other hand, featuring heterosexual masculine demands that are utilized from a place of revindication and irony. The result is these excessive bodies. From there, we are made to reflect on the very contradiction of the image in which we currently live: the use of filters and selfies are, at the end of the day, deformation and alterations of reality.”

Raquel Manchado, founder of the editorial project Antorcha, which has been compiling the graphic history of misogyny and gender stereotypes in popular culture for years, agrees with this interpretation. “The starting point seems to be the heterosexual male gaze, that most omnipresent imaginary, but these physiques could also originate in children’s fantasy, which neatly sublimates that imaginary. It is possible to begin from the hypersexualization without resulting in a mere sexual object. It’s clear that this goes much further: it’s about visualizing yourself and designing yourself in a nearly unreal and excessive form that doesn’t exist in nature. It doesn’t even need to.” Agnes agrees with this concept of the women with an extreme physique that appears to the male gaze as a mixture of sexual goddess and mother: “There’s something of the paradoxical return to childhood in the hypersexualized woman, as if her impossible silhouette were winning the battle against the dominant man and provider, inverting the rules of the game. The man is infantilized by her side.”

But is it art?

The 21st century has brought with it a kind of condescending gaze towards any form of aesthetic divergence, rushing to label it as performance, revolution or art. “Whether these extreme bodies are considered art is determined by the intentionality with which they have been constructed,” says Pardo. The late Anderson, for example, had very clear references, and they weren’t hanging in any museum. “I remember wanting to get cosmetic surgery when I was 18 years old. I was watching porn and I always loved the fake look … I knew the look I wanted was the very, very fake stuck-on look.” Raquel Manchado believes that “this personal construction is nothing but art, even though they are total outsiders to contemporary art and some artists use and phagocytize their image.” She also highlights their role as icons of dissidence, which often turns them, as in the case of Ferrari or Anderson, into icons for LGBT spectators: “These women embody disobedience, they do not comply with what is expected of them. Imagine their family reunions. I don’t think their parents are proud that their daughter has willingly gotten impossible tits. But they are.”

The two agree, however, on one reference: the French artist Orlan (Saint-Étienne, 76 years old), who in the ‘90s, as Pardo explains, “underwent a series of cosmetic operations as a way of revindicating the carnal body: lip augmentation and silicone inserts on both sides of the forehead as a gesture in opposition of Western beauty patterns that are forced on women’s bodies.” They also mention Carolee Schneemann, Marina Abramović, Ester Ferrer and Cindy Sherman. “Contemporary art has worked a lot on all this to speak of deformed, fragmented or monstruous beauty and to dismantle the construction of female subjectivity,” says Prado.

Beyond these artistic considerations lie the physical and psychological impacts. A few weeks ago, Sabrina Sabrok said on an Argentine television program: “I know that [the weight of my breasts] affects my health, but I have to carry on as best I can. Right now, I can’t do sports, I can’t do anything, they weigh too much and my back is too small.” For the individuals who have found fame and lifestyle thanks to an extreme anatomy, to change it would mean losing their job.

In the article in The Guardian that announced Ferrari’s death (a suicide that has been regarded dubiously for years, with her husband and manager under suspicion), it explained that “she wore a specially engineered bra day and night and could not sleep on her stomach or her back (they interfered with her breathing). She was afraid to travel by plane in case they exploded.” Another passage from the obituary: “Ferrari lived in constant fear, as she mimed her songs and took off her clothes in club after club around Europe, that some madman would jump up on the stage and try to puncture them.”

Pain and glory

Pandora Peaks never became relevant in any kind of movies besides the erotic. Other porno actresses, like Leanna Lovelace and Wendy Whoppers, who rose to the heights of fame in the industry after their operations to get mega-sized breasts, saw themselves lose it all after getting them removed due to the health problems they caused. But while they supported their weight, Ferrari, Sabrok and Anderson found fame on television programs and even ventured into musical projects. Ferrari’s best-known song was called Airbag Generation and she was a contributor to the hit British show Eurotrash, which was hosted for years by Jean Paul Gaultier. Her fame surpassed the limits of pornography and eroticism.

In the case of Ferrari and Sabrok, television programs around the world have received them with the usual condescension shown by someone facing a curious-looking mythological creature. This seemed to be the moral: the world is obsessed with overgrown breasts, and there is a crack in the system that allows you to live off them, if you can stand them.

On the other hand, while porn and entertainment glorify big breasts, fashion ignores them. And many doctors, making use of common sense, decline to make their prothesis bigger. Sabrok (who says she has undergone 16 surgeries in her breasts alone) declared: “In the United States they asked me how I’d gotten them so big. They said, ‘Where did they do that to you?’”

The nightmare so feared by Ferrari became reality in the case of the late Anderson. In the spring of 2022, she showed her followers a video of her left breast, which had turned into a jumble of skin after an infection led to sepsis and the implant popped out of her skin. The British tabloid press claimed, flatly, that it had “exploded.” Anderson herself told how the Belgian surgeon who operated on her should never have let her undergo surgery. In the months before her death, she had her breast reconstructed, but continued to suffer problems. Another social media star with inordinately sized breasts nicknamed Mary Magdalene announced that one of her prostheses had also given way in the spring of 2023. The Daily Mail ran the headline, “Surgery-addicted model’s 38J breast implant BURSTS leaving her with a lopsided ‘alien uniboob’” (capitalization from original headline). In the collective imagination, the tragedy was a joke, whether represented in the headlines or on television. That was already the case in the ‘90s. In the “Lolo Pops” segment — which Ferrari presented on Eurotrash — one of the bumpers showed Ferrari’s breasts exploding, with comic sound effects, while she flew off and disappeared.

The tradition continues, now sponsored by platforms like Onlyfans, where the border between pornographic and merely massive has definitively disappeared. The title of woman with the largest breasts in the world is now as disputed as an apocryphal Big Mac index. A young woman named Lourdes García boasts the largest breasts in Spain. Leia Parker claims to have the largest breasts in the United Kingdom. A Brazilian woman, Sheyla Hershey, says that she has beat Sabrok’s record. “Porn is so omnipresent that it overflows into our daily reality,” says Agnes. “Today it is more accessible than music, literature or bottled water, in the sense that it is free and multi-niche and in an intimate way, it is seen as a fundamental right. Its shadows bring collateral damage, but its users are not yet willing to cast a light on those areas.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.