Between jokes and discontent: How communism is winning the internet

With funny memes referencing Soviet leaders and nods to Marxist aesthetics pervading online culture, young people are looking toward the communist past with a mixture of irony and curiosity

In a scene from the Italian film A Brighter Tomorrow (2023), Nanni Moretti — who both directs the film and plays a film director in it — tries to explain to one of his colleagues that in Italy, there were actually many communists, and that no, they weren’t Russians who had snuck into the country, as his young interlocutor assumes, but Italians who belonged to the powerful PCI — the Italian Communist Party, which, during the years of the Historic Compromise (Compromesso storico) in the seventies, formed part of the national government. The scene is an exaggeration — a joke about the ignorance of some young people, or about how far 2023 is from the Marxism that shaped Moretti’s generation during its formative years (the director was born in 1953). But are these references really that outdated and obscure? Have we not been consuming communist icons, now fully integrated into the capitalist market system, for years? Or more recently, seeing and sharing memes that reinterpret and modernize the messages of socialism?

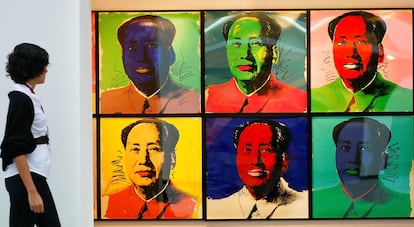

Apart from the quintessential example of the ubiquitous Che Guevara T-shirt one finds at a flea market, there have been, and continue to be, all kinds of reappropriations, quotations and reinterpretations of socialist or Soviet culture and symbology. They appeared in the contemporary art world during the last third of the 20th century (when, after the world learned of Stalin’s crimes, few Western intellectuals defended the USSR in the West without qualms) and their meaning, scattered and paradoxical (a quality typical of postmodern art), oscillated between satire, the ambiguous defense of a system that was beginning to collapse, and the depoliticized plundering of Marxist aesthetics.

From Sots Art to “Sovietwave” to “communist-chic”

The invention of Sots Art, or Soviet Pop Art, is usually attributed to the couple Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid, both artists from Moscow exiled in New York. If, as most critics would have it, American pop art criticized or exposed the contradictions of consumer society through everyday objects and mass-culture myths (from Marilyn to Mickey), Sots Art, in the 1970s and 1980s, did the same with the most popular and revered elements and characters on the far side of the Iron Curtain — from Lenin to the cosmonauts. Komar and Melamid’s work, like that of fellow Russian artist Erik Bulatov, immediately circulated through major art museums and galleries in the West and, though in the case of the exiled couple, their critical perspective was evident (they faced censorship and repressed in their home country), it nonetheless gave rise to a certain confusion surrounding their message, or lack thereof. Moreover, Sots Art, which was almost a variant of pop art, followed the same maxim that Warhol applied to determine whether or not he liked a given work: “The more you look at the same exact thing, the more the meaning goes away, and the better and emptier you feel.” A phrase that, it bears emphasizing, could describe today’s diffusion and reproduction of various viral internet phenomena perfectly.

In 1998, fifteen years after Komar and Melamid’s paintings were first hung at the MoMA, and were first seen in New York, talk of “communist-chic” began to spread. Colin Robinson, a publisher at Verso Books, joked in an interview that he planned to sell the publishing house’s 150th anniversary edition of the Communist Manifesto at Barney’s, a luxury department store. The joke spread across media, and the re-print of the Manifesto, with a new introduction by Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, wound up selling thousands of copies in shopping malls and bookstores across the country, which promoted the book with a display typical of any other seasonal bestseller. The new edition of the Manifesto had become a consumer good, and a kind of fashion accessory, with previous versions of the book still widely available for less than a dollar. Robinson himself, a self-confessed leftist, recalled the paradox with a sense of humor, as did members of the Communist Party USA, who thought that the book’s unexpected popularity might serve to spread Marx’s ideas among a public largely unfamiliar with them.

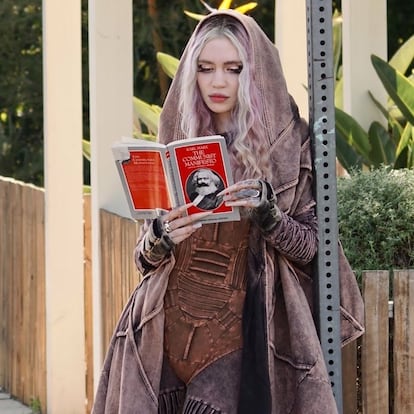

Much more recently, the singer Grimes, Elon Musk’s former partner, was seen walking around with a different copy of the Communist Manifesto, only to later declare that it was just a prank for social media. Following the online aesthetic, contemporary artists like Gala Knörr or Michael Pybus incorporate Soviet symbolism into their paintings on virtual narcissism. “The problem with these works that are presented as a kind of joke, or as playful irony, is that they get quickly exhausted,” argues Alberto Santamaría, a philosopher and Professor of Art Theory at the University of Salamanca in Spain. “It’s a form of situationism without the situationism, and if you take politics out of situationism, all you’re left with is Amélie. When you depoliticizing situationism, everything ends up being just a silly game, a mere empty gesture.”

In the years since the anti-globalization revolts in Seattle and across the world, the aesthetics of protest have been more connected to anti-capitalism in general than to the vindication or condemnation of communism specifically. But Santamaria warns that any subversive art, even the most serious and sincerely committed, will find insurmountable limits much sooner than one might think: “Within the culture industry, anything is possible, but on one condition: that the culture industry itself is not called into question. One of the great achievements of neoliberalism is precisely the subtlety with which it operates, separating cultural creation and economy. We need bombs planted on the underbelly of the cultural industry, but that’s impossible right now, because the double bind in which the artist is trapped stems from his own precariousness and individualism.” Perhaps this is why humor can serve as an effective Trojan horse.

Enter the age of socialist memes

“Imagine having been a propaganda minister for the German Democratic Republic and having a teenager on the internet outdo you thirty years after your nation is gone, lol,” commented a YouTube user in a “Laborwave” video that mixes East German imagery with electronic melodies. There are nuances that distinguish them, but both Laborwave and Sovietwave are synthesizer-based genres characterized by an aesthetic somewhere between Soviet nostalgia and retrofuturism (they imagine a future in which the Soviet Union is a global superpower exploring the far reaches of the universe). And they are not just marginal phenomena: Sovietwave tracks have millions of views online and appear across virtual communities accompanied by messages that make it impossible to distinguish homage from parody (the internet being a place where no one takes responsibility for their opinions). A similar phenomenon, which likewise swims in the swampy terrain of irony, happens with communist-themed memes, like the famous Bugs Bunny who wants to claim everything as “ours.”

In any case, the dissemination of this content during a time of widespread social unrest, inequities in the world of work, and crises at so many levels of society is no coincidence, and may very well express a growing and sincere interest in the communist universe: “There are no longer the kind of dogmatic constructions surrounding the classical idea of socialism that existed in the 19th or 20th centuries,” explains Clara Ramas, a professor at Complutense University of Madrid and an expert on Marxism. “The notion of so-called capitalist realism prevails: it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, which has become an inescapable frame of reference. But this is something Marx already knew when he wrote, in the Manifesto, that communism is a specter — a metaphor he used in other texts, which means that communism is a presence that, even if it’s not realized, can never be scared away.”

“As for memes and content that refer to old forms of communism or that use them in a critical, ironic or nostalgic way, they do this not so much because of anything specific the USSR represented at the time, but because it’s something from the 1920s and 1930s,” Ramas says. “What is most notable here is the kind of varnished image of a better past, of a golden age people long for in the present; it’s an understanding that the present represents a kind of nihilistic or relativistic collapse, where there are no foundations, and that sees the past as a time when there was at least some solid program to cling to. I think this is a mistake, or a terrible trap.”

In fact, the philosopher explains, Marx’s famous phrase about history happening “first as tragedy, then as farce” is an invitation to creatively reappropriate both symbols and historical events: “What it tells us is that, while events may repeat themselves, any reconstruction of those events, any introspective society produces comedy as a superior form, as Marx also pointed out. The meaning of comedy is precisely to become aware of our actions, to see them from a distance, and to be able to laugh at ourselves.”

In the same way that Sot Art aimed to send a message against totalitarianism, the same faces (Lenin’s, for example) now appearing on our phone screens, more than thirty years after the collapse of the USSR, and serve as encouragement for precarious youth exploited by the market, without necessarily vindicating everything that was done during the Soviet era. “That is why,” Ramas concludes, “in the face of conservative readings that argue that this era of memes and social networks is an era of alienation, I believe it is an era of enormous lucidity and introspection, because the use of comedy implies distance and self-reflection. And the meme has taken this to its apotheosis, making extremely refined discursive work out of the object of the meme, which ends up being the meme itself.”

Punk, still not dead

Beyond the rise of the Marxist meme, Marxism appears to have returned with force in punk music culture as well (a milieu that never completely abandoned the ideology). In Spain, a punk band from Granada known as the La URSS, in songs like Más allá del future, and the band VVV [Trippin’you], from Madrid, features political messages on nearly every track, echoing the most workerist expressions of British postpunk. The Alicante trio Futuro Terror promotes the legends and myths of the Soviet universe because, as José Pazos, their singer and guitarist, explains: “We don’t want to ignore a culture that has also shaped the world. That is, people tend to take for granted that Anglo-Saxon culture is something natural, when it’s not. For me, the influence of Soviet culture is something similar, though even more interesting because it’s unknown, and because it they’ve tried to hide or misrepresent it.”

While Pazos says he would like to see a more concerted reappearance of orthodox Marxism (“understanding that this is not the same as Stalinism”), he says that it is “currently quite difficult to find discourses that go beyond just social democracy in disguise,” and that “expressions of serious Marxism adapted to our times, and that don’t fall into Nazbol-style nationalist nonsense [National Bolshevism], are very much in the minority.” So, what has been the reaction at his performances: ignorance, or a rejection of his message? “What I see the most, and what horrifies me the most, is the absurd views of people who say that ideologies themselves are outdated, when obviously by making such a statement they are positioning themselves in staunch defense of capitalism.”

But even the people who think this way will, at the end of another grueling day, open their phones to a meme with Marx’s face on it, or a song about the failed, but for many still inspiring, Soviet project. And maybe they will connect this fleeting image to their own sense of dissatisfaction. In such case, the tool that Bertolt Brecht famously referenced when he quipped that “art is not a mirror held up to reality but a hammer with which to shape it” will have come back to do its work. Memes and songs published on YouTube may not be the most powerful artforms, but they continue to strike with relentless persistence.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.