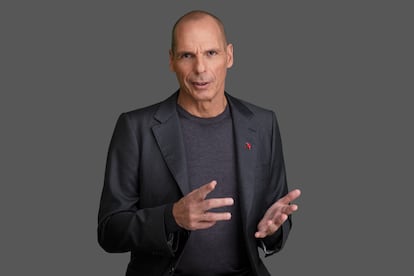

Yanis Varoufakis: ‘Capitalism is dead. The new order is a techno-feudal economy’

The former finance minister of Greece warns that politicians can’t do anything about the growing power of big business

Yanis Varoufakis, 62, turns on his laptop and enters the Zoom meeting. He sits in the studio of his home in Athens, Greece. One of the most well-known and influential economists in the world, he offers a kind greeting before beginning his conversation with EL PAÍS.

For the first time in many years (he had promised his wife, Danae) he took a few days of vacation in August, in the Aegean Sea. But, soon after, he was back at work, keeping track of all his appointments (including this one).

Varoufakis studied at a private school, before completing two postgraduate degrees in Mathematics and Economics at the universities of Essex and Birmingham. He has taught in Australia, the United States and, since 2000, has lectured in Economics at the University of Athens. But his life — and his “myth” — is intertwined with politics.

He served as the finance minister of Greece between January and July 2015. Those were difficult days, when he dealt with Wolfgang Schäuble — who served as finance minister at the time under former German Chancellor Angela Merkel — in the familiar story that was the seemingly endless Greek sovereign debt crisis. This was when the Troika — the European Central Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the European Commission — put the squeeze on Greece for every last euro, as a condition for issuing a financial rescue package. In July 2015, citizens voted against austerity and the social suffering it would cause. Although his side won the referendum, Varoufakis resigned, after five months in office.

In February 2016, he created the Democracy in Europe Movement 2025 (DiEM25). And, in March 2018 — as a former member of the left-wing Syriza party — he founded MeRA25, the “political branch” of the movement. He then returned to the Greek Parliament as an elected legislator. Since then, this “libertarian Marxist” — this is how he defines himself, with an evident sense of provocation — has also had great success with bestsellers, such as Talking to My Daughter About the Economy and Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism. Brilliant with titles, one of his latest articles is called Let the Banks Burn. He has also coined several terms for our era, such as “cloud capitalism,” “de-dollarization,” “global austerity” and “techno-feudalism.” Although he may not intend it, many of his columns are somewhat impregnated with the pessimism of the philosopher Emil Cioran (1911-1955) and his temptation to exist: “Writing is a matter of life or death.”

Without a doubt, his latest book is imbued with a certain sadness. It was born from a conversation he had many years ago, in 1993, with his communist father, Giorgios.

As we struggle with our internet connection, Varoufakis jokes: “Now that computers can talk to each other, will this make it impossible to overthrow capitalism? Or will technology finally reveal its Achilles’ heel?”

Question. Perhaps it has already revealed it?

Answer. Amazon’s Alexa, for example, is nothing more than a portal. Behind it, there’s a centralized totalitarian system created to satisfy its owner, Jeff Bezos. [This system] does four things at the same time: it trains us to tell it what we want. It directly sells us what we know we “want,” regardless of any real market. It makes us reproduce its capital in the cloud (that is, it’s an immense behavior modification machine), because thanks to our work — which is done without remuneration — it publishes reviews or rates products. And finally, it amasses enormous profits from the capitalists who are operating within this network… generally, 40% of the sticker price [of products]. This isn’t capitalism — welcome to technofeudalism!

Q. What’s your hypothesis?

A. Capitalism is now dead. It has been replaced by the techno-feudal economy and a new order. At the heart of my thesis, there’s an irony that may sound confusing at first, but it’s made clear in the book (Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism). What’s killing capitalism is capitalism itself. Not the capital we’ve known since the dawn of the industrial age. But a new form, a mutation, that’s been growing over the last two decades. It’s much more powerful than its predecessor, which — like a stupid and overzealous virus — has killed its host. And why has this occurred? Due to two main causes: the privatization of the internet by the United States, but also the large Chinese technology companies. Along with the way in which Western governments and central banks responded to the great financial crisis of 2008.

Varoufakis’ latest book warns of the impossibility of social democracy today, as well as the false promises made by the crypto world. “Behind the crypto aristocracy, the only true beneficiaries of these technologies have been the very institutions these crypto evangelists were supposed to want to overthrow: Wall Street and the Big Tech conglomerates.” For example, in Technofeudalism, the economist writes: “JPMorgan and Microsoft have recently joined forces to run a ‘blockchain consortium,’ based on Microsoft data centers, with the goal of increasing their power in financial services.”

Q. It’s been nearly 600 days since the war in Ukraine began. What do you think about this? And what impact does it have on the economy?

A. My thoughts are the same as on the first day Putin invaded Ukraine. It’s a war that will end quickly if there’s a peace agreement… otherwise, it can last for decades. If it continues, there will be no winners — only losers. Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians dead, hundreds of thousands of Russians dead. It will impoverish Europe and make Africa more miserable. The West must offer the Russian leader a very simple agreement, [bringing the territorial lines] back to where they were before February 2022. In exchange, Ukraine will never be a member of NATO. It’s the Austrian solution: it’s part of Europe, it has an army, it’s a liberal democracy but not part of the organization. This is the only possibility that coincides with Ukrainian interests, while avoiding sacrifice and impoverishment.

Q. Europe is aging, growth is slow, the economic center of the world is moving to South Asia and Southeast Asia. What kind of future awaits the Old Continent? Will it become a luxury resort for millionaire foreigners on vacation?

A. There won’t be a breakup of the European Union. It has been saved by Mario Draghi (the former president of the ECB) thanks to the injection of billions of euros. We’re entering a period of decline, though. About a month ago, I met with the president of Mexico, López Obrador. The EU doesn’t concern him. Of course, Mexico wants to have a good relationship and everything, but what counts for them is the United States and the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa).

Think about geopolitics, especially after the war in Ukraine. Think NATO — whatever that is. It’s not a European foreign policy: it’s NATO’s foreign policy. The secretary general decides our policies for us. But imagine — I wish this were the case — that, tomorrow, there’s a table for peace talks. Who would be sitting at the table? Zelenskiy and Putin… and Xi Jinping, Modi and Biden. Who would represent Europe? Nobody. We don’t have leaders. Poles, Estonians and Lithuanians don’t trust Emmanuel Macron or Germany’s Olaf Scholz, because they think they’re too close to Putin. But can you imagine an EU represented by someone other than Germany or France? It’s worse than a crisis. We (Europe) are becoming irrelevant.

Q. Today, some German politicians recognize the error that was austerity, which was the policy you fought against when you were negotiating the bailout for Greece.

A. They only say that after they retire. You should be judged by what you do when you are in the administration. That’s what counts. The rest doesn’t matter to me. Christian Lindner — the current German finance minister — is pushing austerity. He’ll never admit that they’re wrong. The German economic model is dying and Europe is close behind it. What are the industries of the future? Solar, wind, batteries and software development. The EU doesn’t even exist [in these fields], because it doesn’t invest in anything. What’s [the EU] going to do about China, which has an absolute monopoly on batteries?

Q. Why is there no equivalent to Amazon in Europe?

A. For the same reason: nobody invests. We’ve wasted 14 years practicing austerity. Germany’s mobile phone system is almost Third World. It’s an underdeveloped country in terms of digitalization. They’ve approved — with all those years of delay — a digitalization budget of $200 billion euros ($212 billion) over the next five years. About 50 billion euros less than expected. Do you know they still use fax machines in Germany?

Q. What powers do politicians have over large corporations?

A. Zero. Once upon a time, politicians had a role… Franklin Roosevelt, Willy Brandt (Germany), Harold Wilson (United Kingdom), or even Nixon. They could change things. Get people to sit around the table. Now, unions no longer exist. There’s no one to sit with [today’s leaders]. If you clash with the system, it eliminates you.

Q. China, Singapore, India, Saudi Arabia — among other countries — have shown that they can grow and generate prosperity, while still being dictatorships or autocracies or nations with dubious respect for human rights. That is, without being democracies.

A. We forget about history. Democracy was never part of capitalism. Already in the 19th century, in Great Britain, the philosopher John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) defended liberalism. He respected property rights, freedom of expression... but liberalism was the opposite of capitalism. The official Chinese party says, well, we’re liberal like the British were. They recognize private property — if you have a house, they won’t take it away from you, you can accumulate as much money as you want, do business. This is liberalism. [But only] as long as you don’t say anything against the party.

Is this so different in Britain? Did you see the coronation of Charles III? There was a professor outside the House of Commons who held up a blank banner. He was arrested for disrespecting the king. This isn’t freedom of speech, is it? Is the United States a democracy? Oh, really? You have a party in government with two different faces. Trump was a poor excuse for a human being. He changed the North American Free Trade Agreement, undid the nuclear pact that Obama had signed with Iran, started the cold war against China. Biden arrived. He was supposed to be the anti-Trump. Has anything changed? No, he’s made it worse. The cold war has gotten worse, there’s more enmity with Iran. Cuba suffers a worse embargo than under the former president. Of course, I would prefer to have dinner with Biden rather than Trump. However, that’s not what a democracy is supposed to be about.

Q. Is feminism compatible with the current economic system?

A. Capitalism only brings enormous, terrible burdens. One is the exploitation of women. The only way women can prosper is at the expense of other women. No, in the end — and in practice — feminism and democratic capitalism are incompatible.

If there’s one thing Yanis Varoufakis is, it’s tough. Perhaps it comes from the days when his father, Giorgios — a communist steel engineer — taught him, in front of the fire of a red brick fireplace (in a modest house), the properties of metals. It has served him well in the gym, in European politics, or last March, when a group of “hired thugs” — in the words of Varoufakis — beat up the former minister while he was having dinner in the popular Exarchia neighborhood of Athens. The “thugs” (who claimed to be activists) shouted at him and accused him of having “sold out to the Troika.” After the incident, the former Finance Minister ended up in the hospital. “We’re not going to let them divide us,” he wrote on Twitter. “We keep going!”

Born in the 1920s, Giorgios — whose parents were Greek — grew up in Cairo, Egypt, before entering the University of Athens to study Chemistry. But he was caught up in the Greek Civil War (1946-1949). He was detained and questioned by the police. He refused to denounce his fellow communists and spent four years in prison as a result. Later, when he restarted his studies, a conservative woman noticed him. Her name: Eleni. Varoufakis’ future mother. In the end, her father’s ideas resonated with her and communism became the landscape of their conversations.

Years later, he would ask his parents what freedom meant to them. His mother said it was the possibility of choosing your partners and your projects. His father replied: time to read, experiment and write. These notions run through all his books.

Giorgios — under Greece’s far-right regime — had many problems finding work. The secret police did everything possible to get him fired. With some good fortune — although the salary was lower than what he was entitled to — the Halyvourgiki Hellenic Steel Industry hired him as assistant to the director. In a kind of delayed justice, he eventually became president of the board of directors.

This was the environment that Yanis grew up in, with stories about prisons, with memories of harshness and reprisals. Perhaps, thanks to this upbringing, his life has been one of perseverance: he holds two doctorates (in Economics and Mathematics), served as finance minister of his country and has taught classes in the United States, Australia and Greece.

Everything begins in childhood — the rest is the inexorable repetition of days.

At the University of Sydney, when he was teaching, he met Xenia’s mother, Margarite — an Australian-born professor of European history, with Greek roots. They fell in love and got married. They went to live in Greece. But the relationship didn’t work out and they broke up. Margarite returned to Australia, without knowing that she was pregnant. When she found out, she returned to Greece — they had to give the relationship another chance. “But it wasn’t working. And she went back to Australia. It was a nightmare. Because I missed my daughter a lot,” he commented in an interview with The Guardian. “As a consolation, I put her to sleep at night via Skype.”

In this fragile emotional state, he discovered by chance, in an art gallery, an installation titled Breathe. It was work by the artist Danae Stratou. A work in which water and earth breathe. He was impressed. They had dinner and fell in love. He now lives in Athens with Stratou and her two children. Danae — who participated in the 48th edition (1999) of the prestigious Venice Biennale cultural exhibition — comes from a very wealthy family. Her father founded the textile company Peiraiki-Patraiki.

Q. Few economists doubt the idea that, to prosper in life, the family you are born into is more important than all the effort you put in.

A. That’s right. The lottery of birth. We live in very unequal societies. The greatest predictor of our future is the wealth and situation of our families.

Q. In another one of your books — Talking to My Daughter about the Economy — you teach Xenia about the threats of capitalism. What kind of world do you think she will live in?

A. I never, never, never make predictions, because if I were forced to answer you, my answer would be very sad. I certainly don’t think things will go well in the future. But this is different from simply giving a weather forecast. Societies lack the right to predict, because what counts is the result of our actions, the result of what we do. We have the moral duty to act.

Q. In your latest book, you note that BlackRock — the world’s largest asset manager, by the amount of assets under management — is part of the problem. When you hear the CEO Larry Fink say that he will continue investing in oil and gas because his clients demand it — despite his supposed commitment to sustainable funds — what do you think?

A. The only solution is to dismantle the company.

Q. Drastic.

A. Well, capitalism must also be dismantled. I’m a leftist, after all.

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.