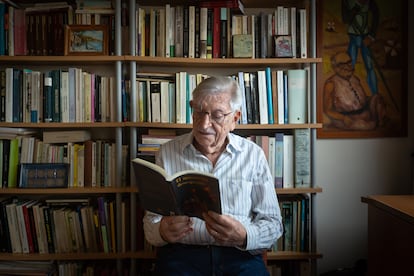

Writer Abrasha Rotenberg: ‘We are not witnessing the triumph of capitalism, but experiencing a poverty of dreams’

The 97-year-old economist, editor, journalist and author shares his remarkable journey of exile, war and revolution, and offers his insights into the future

Abrasha Rotenberg just turned 97 years old. As a child, he was raised in the fields of Soviet Ukraine amid the fervor of Stalinist Moscow. As a Jewish teenager, he grew up in Buenos Aires among the immigrants that flooded in during the interwar period. As an adult, he became an economist educated in Argentina and Israel, a newspaper editor exiled by the Argentine military junta, and the father of two well-known artists – singer Ariel Rot and actress Cecilia Roth. Rotenberg spent half of his life traveling back and forth between Madrid and Buenos Aires, but for the last 10 years he has settled in the Argentine capital to write fiction.

Rotenberg recently published El moscovita desesperado (or The Desperate Muscovite), a collection of short stories that takes readers on a voyage from Moscow through the ideologies and contradictions of the 20th century, ultimately landing in the turbulent Buenos Aires of the 1970s. This is his second foray into fiction – he published his first novel, La amenaza [or The Threat] in 2020 when he was 93. It’s a story based on his own life of exile: a young man born in the Soviet Union and exiled to Argentina where he discovered his Jewish heritage at a time when the country was flirting with fascism; and a newspaper editor forced to flee Argentina decades later under threat by the military dictatorship.

Question. The main character of your novel is a young Jew who gets involved with a group of Nazi sympathizers from Argentina. Is it a true story?

Answer. It’s a true story that took me a long time to tell. I lied to them and said I was Finnish. The lie pained me for a long time. It happened 80 years ago.

Q. At one point in the book, they’re all in a car listening to reports about the battle that sank the Admiral Graf Spee, a Nazi ship, in Argentina’s La Plata River in 1939.

A. That’s right. I was in a viper’s nest of right-wing and fascist groups that culminated in the 1943 coup d’état [in Argentina].

Q. Uruguay wanted to melt down the Nazi eagle emblem from the ship and forge it into a peace dove. What do you think about that?

A. I would put it in a museum. Why erase history?

Q. What language did you speak in your childhood home?

A. I was born in Teofipol, a village of 900 in western Ukraine. School was taught in Russian, but we spoke Ukrainian at home like everyone else. During that period, there were conflicts regarding Ukrainian identity because Stalin wanted to impose Russian culture and language on the entire Soviet Union.

Q. Why did your family leave the Soviet Union?

A. The revolution was a problem for us. Jews like my father were merchants, and the revolution exalted workers and peasants. My father had no place in that society – he was considered a parasite. One of his brothers had married and gone to Argentina, so my father left to join him around the time when I was born. I went later.

“August 1976. Spain felt a breath of fresh air – it was a time of great hope. Then everything got complicated”

Q. And your mother?

A. My mother was a courageous woman who fearlessly embraced challenges. Her family, by today’s standards, could be described as politically active and intellectually inclined. At home, they immersed themselves in reading and engaged in impassioned discussions. When my father departed, my mother found employment in Magnitogorsk [eastern Russia] where we lived for a year in a frigid, tin shack surrounded by oppressive pollution. She worked at a demanding job in a steel foundry, but that one year of sacrifice gave us the privilege of living in Moscow. My mother was able to get a great job and home for us. It was a collective house across from Red Square.

Q. What do you remember about Moscow?

A. Hours spent sitting on our front stoop gazing at long lines of people. The vast Soviet Union, lining up for days to enter Lenin’s mausoleum and see his tomb.

Q. Why did you leave Moscow?

A. We lived seven years without my father in the Soviet Union. When he was finally able to obtain visas for us, we left with a group that was supposed to board a ship to Argentina in Bremen [northern Germany]. We made it to Berlin in November 1933 – I was seven years old – and something unfortunate but also lucky happened to us there. Some of our group contracted trachoma [a bacterial eye infection] so the German government quarantined them. But since we were all traveling as a group, we had to stay behind as well. Hitler was in power and the German government paid for our stay in Berlin – about two months. I saw things there... [laughs]. I was turning into a Nazi. There were these amazing, vibrant kids singing and marching in the streets. I had come from a pretty sad place – communist Russia – but in Berlin I got swept up in this contagious optimism. Here I was, a Jew, living in Berlin at Hitler’s expense!

Q. What was it like when you made it to Argentina?

A. This is where I discovered my Jewishness. I grew up in La Paternal, this very poor neighborhood with factories and dirt roads. It was a cultural melting pot. We had Italians, both fascist and anti-fascist, and then there were Loyalist and Republican Spaniards. Everyone was divided there, but the one thing everyone agreed on was their prejudice against Jews.

Q. Was that division evident in politics at the time?

A. In 1933, Argentina was very politically divided. When the war [World War II] broke out, things really started to change. There was this massive event at Luna Park [a multi-purpose arena in Buenos Aires] with 20,000 people rallying for the Nazi party. Most people supported the allies, but there was this powerful minority, especially in the Armed Forces, who had German backgrounds and liked the regimes of Italy and Germany. And then the 1943 coup happened and Juan Domingo Perón took over. He had this enormous admiration for Mussolini.

Q. How does your arrival in Argentina compare to your exile in Spain?

A. I feel very much like an Argentine, but Spain sparked political zeal in me for the first time. I was 13 years old when the Civil War broke out, and I immediately sided with the anti-Franco forces. That’s when I began to understand politics, although I was naive. We would collect aluminum from cigarette boxes and send it to the Republicans, who ground it down to make gunpowder.

Q. You arrived in Spain during the transition to democracy.

A. August 1976. Spain felt a breath of fresh air – it was a time of great hope. Then everything got complicated because of the vast gap between dreams and having the means to achieve them.

Q. You left Argentina because you were the director of La Opinión, a newspaper that made life difficult for the dictatorship.

A. I was oblivious to the threat in Argentina. Even though several of our reporters had been murdered, I foolishly dismissed the warning signs. One night, my son Ariel and his friend Alejo Stivel, who would later form the band Tequila, were arrested and held all night at the police station. People told me, “Run for your lives or stay here forever.” That terrifying warning made up our minds to leave.

Q. What was it like being in charge of La Opinión?

A. It drove me crazy. It was terrible because instead of 80 journalists, we had 80 activists. But it was an experience that I have always appreciated. Something was happening at La Opinión that is impossible to imagine in today’s media: we had writers of all political stripes.

Q. How do you publish a newspaper under a dictatorship?

A. Many little miracles helped. They did horrible things to us. During the Lanusse administration [1971-1973] we saw an increase in sales, which made us very happy. Our regular sales were around 30,000 copies, and in just a few weeks sales shot up to 40,000, 45,000, 60,000... Then the newsstands began complaining that they weren’t getting their orders, so I naively printed more copies. A few weeks later, thousands of newspapers were returned to us – they had never been distributed. That [government] maneuver cost us a fortune.

Q. You kept on publishing for a few more years...

A. We had to negotiate everything. Jacobo Timerman [the founder of La Opinión] wanted to shut down, but we voted to negotiate. The government was clear – do not write anything critical about the Army or Lanusse, and don’t advocate for the guerrillas. We reached an agreement but it was the newspaper’s worst crisis.

Q. How do you view the state of journalism these days?

A. It has lost something fundamental – respect for opposing viewpoints. It has become very difficult to have a discussion. The joy of coming together, having conversations and respectfully sharing differing opinions has been lost.

Q. Does this political environment remind you of anything?

A. Not to these extremes. The world is experiencing a significant shift to the right. There is a growing disillusionment with the left and socialism, both of which I steadfastly defend as the most effective remedy to the challenges of our time. It’s a path toward fairer distribution and fostering a more equitable world where the state plays a pivotal, regulatory role and makes sure the benefits of society are shared equally.

“The world is experiencing a significant shift to the right. There is a growing disillusionment with the left and socialism, both of which I steadfastly defend as the most effective remedy to the challenges of our time”

Q. Do you consider yourself left-wing?

A. Although I don’t identify as a socialist, I find value in certain aspects of Marxist economics. According to this framework, the ideological superstructure is shaped by the underlying economic infrastructure. It’s the age-old truth that society and its prevailing ideology are shaped by the means of production.

Q. It seems simple, so why are people disenchanted with the left?

A. It’s in turmoil and doesn’t know what to contribute. However, there is a bigger underlying issue we no longer talk about. The pandemic changed our way of life and intensified individualism. People no longer want to meet each other face-to-face. I understand that my perspective may be skewed – I’m a 97-year-old man with very few peers from my generation. Younger generations want to live their own way.

Q. Do you see this generation as very different from your own?

A. There is one thing that sets us apart. Looking back on my youth – we wanted to change the world. We wanted to make it more equitable. Some had extreme methods, some were more measured, and others were just dreamers. But we all wanted change. I don’t think young people now want to change the world, they just want to find their own place in it, the best one they can get.

Q. What is the biggest issue with that?

A. We seem to be unaware that we find ourselves in the most tumultuous revolution of our time – the convergence of knowledge and artificial intelligence. The industrial revolution took centuries to reach its zenith, but the computer revolution leaps forward in mere weeks and months. Everything could change in a couple of years and we’re not ready for it.

Q. Has capitalism definitively triumphed?

A. We are not witnessing the triumph of capitalism, but experiencing a poverty of dreams.

Q. We’re no longer idealists?

A. Something dramatic and natural happened. The ideologies that were part of my youth are worn out – no one believes in them anymore. My generation had answers for everything. Now we don’t even have questions. It’s terrible. No one dreams anymore of an ideal world.

Q. Why not?

A. I was born in 1926, nine years after the [Russian] revolution that was going to change mankind. Many things happened between 1917 and 1926. Mussolini invented fascism, Hitler rose to power in 1933, and the Spanish Civil War erupted in 1936. In 1939, World War II began. From that time until now, not a single day has passed without the resounding echo of gunfire.

Q. Does that worry you?

A. I’ve thrown away all my calendars and just mark time by my clock. I look at it and say to myself: I have two more minutes of life – wonderful!

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.