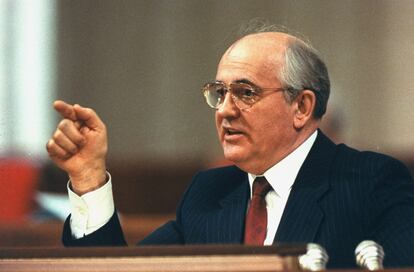

Gorbachev, the great Soviet reformer and father of ‘perestroika,’ dies at 91

The reformist politician became a critic of modern Russia and its attacks on democracy

Mikhail Gorbachev has died in Moscow at the age of 91. Celebrated abroad and despised by many at home, the last leader of the Soviet Union and great reformer breathed his last in a hospital in the Russian capital, according to the state agency Tass. Born in Stavropol, Gorbachev was one of the key figures of the 20th century. He blazed a path to democracy for tens of millions of people and eased the Cold War that had paralyzed the world for four decades.

In Gorbachev, His Life and Times, a lengthy biography of the former Soviet leader, William Taubman writes that the Soviet Union collapsed as a result of Gorbachev strengthening the individual at the cost of the state. Today, his democratic legacy has all but collapsed in Russia. The government has violated most of the disarmament treaties that he signed. Many of the taboos that his reform processes dismantled have been reinstated, particularly since Russian president Vladimir Putin ordered the invasion of Ukraine last February 24 in a war that has shaken the world and isolated Russia.

In recent years, the last leader of the USSR had become a rather isolated figure in Russian politics. Most of his contemporaries are now deceased. The state media ignored him because of his criticism of anti-democratic issues in Russia and his veiled statements against Vladimir Putin’s government. From time to time, voices have proposed prosecuting him for inciting the collapse of the Soviet Union, which President Putin calls the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century. The reformist politician had refrained from commenting publicly on the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine, although his friend Aleksei Venediktov, the former head of Echo of Moscow radio, recently claimed that Gorbachev had said privately that he was “upset” because his “life’s work” had been “destroyed.”

The politician had no immunity, and his eponymous non-profit organization had to tread carefully to avoid being labeled a “foreign agent.” In recent years, Gorbachev, who lived alone in Moscow, had suffered from significant health problems. His daughter, his two grand-daughters and his two great-grandchildren live outside the country.

Originally from a rural background but educated at Moscow State University, where he studied law, Gorbachev rose to the top of the Communist Party. As he ascended, his doubts about the system became more intense, as his biographers have recounted. Those concerns shaped his career, first as Soviet General Secretary and later as President. And they led him to carry out a momentous reform of Soviet society between 1985 and 1990, introducing the economic restructuring policy of perestroika, as well as glasnost, the government transparency policy.

His reforms included the democratization of the party, the transformation of the country into a presidential republic and a constitutional reform to allow multiple political parties. Gorbachev also ordered that parliament proceedings be televised. The changes he pushed through helped eliminate some of the worst repression of the Communist system.

He paved the way for free enterprise and open borders. His intention was not to overthrow the USSR, but to save it, and to make socialism great again. He promoted a vision of the Common European Home from the Atlantic to Vladivostok. He also promoted impressive changes in foreign policy. He signed a series of key arms control agreements with the United States and participated in the conclusion of the Cold War, which earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1990. Those initiatives, however, unleashed all kinds of centrifugal forces that he couldn’t control, including an economy in serious trouble, popular discontent and the yearning for independence in some Soviet republics.

Some called Gorbachev “the man who changed the world” for his role in the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, which meant not only the unification of Germany but also the symbolic end of the Cold War. Hundreds of documents, declassified only a few years ago, revealed that the last leader of the USSR never considered the option of using force to prevent collapse. The demolition of the wall was a decisive crack in the fall of the Soviet empire. It was followed by the collapse of the remaining Eastern European Communist regimes: Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria. Thus ended Moscow’s control of the former Eastern Bloc.

Gorbachev, who lived through a coup attempt by hard-line communists, was hopeful that he could hold the country together, even after the republics that made up the USSR declared their independence. That hope ended with the creation of the Commonwealth of Independent States, which brought together 11 of the former Soviet republics. “What happened with the USSR was my drama. And a drama for all those who lived in the Soviet Union,” he commented in an interview.

On December 25, 1991, a holiday in the West but not in Russia, Gorbachev addressed the country to announce his resignation. In his speech, he explained that although he had always supported the sovereignty of the republics, he had also been a strong supporter of the unity of the state, but events had taken another turn. On that day, in the Kremlin, the Soviet flag was lowered for the last time.

In 1996, he unsuccessfully tried to run for the presidency of Russia. With the rise of Putin in power and an increasingly authoritarian regime, the reformist politician became a critic of modern Russia, its attacks on democracy and the widening of economic and social disparities resulting from privatization, corruption and years of patronage.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.