Gods, tombs and Nazis: the Third Reich’s bad relationship with Egyptology

Anti-Semitism and the Hitler regime’s obsession with the past of the Aryan peoples put the brakes on the study of the ancient Pharaonic civilization in Germany, despite what is shown in ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’

When one thinks of Nazis and Egyptology, the first thing that comes to mind for many of us is the burnt palm of the hand of the fictitious Gestapo agent Toht on which is engraved the medallion of Ra, the key to the location of the Ark of the Covenant in Raiders of the Lost Ark, the first installment of the adventures of Indiana Jones.

The sadistic Sturmbannführer Arnold Toht (the surname is an Egyptian wink, recalling the name of the scribe god Thot, although he, devoted to wisdom and justice, would never align himself with the swastika), is, with his leather outfit even in the desert and his air of Himmler interpreted by Monty Python, one of the most successful villains of the Indy series. He is part of a team of Nazis embarked on a search in Egypt for the precious (and lethal) relic, a group that also includes two other officers, Oberst (Colonel) Herman Dietrich and his right-hand man Major Gobler. In the film, Dietrich and Gobler are, in 1936, militarily in charge of the excavations in the ancient “lost” pharaonic city of Tanis, east of the Nile Delta, to find the biblical artifact, which Hitler wants to appropriate, informed of its destructive capabilities.

The image shown in Spielberg’s film of German troops dressed as the Afrika Korps, Schmeisser machine guns and rifles in hand, guarding the work of hundreds of Egyptian workers is a stupendous Egyptological nonsense. The archaeologist who co-directs the excavation for the Nazis is a Frenchman, Indy’s archenemy René Emile Belloq, in the service of Hitler. It is true that Tanis was excavated at that time and that it was done by a Frenchman, but not an unscrupulous mercenary like Belloq, but a selfless and courageous savant, Pierre Montet (1885-1966), who had won the Croix de Guerre in the First World War. In 1939 Montet discovered not the Lost Ark but the tombs of the kings of the XXI and XXII dynasties, one of the great milestones of Egyptology, comparable to the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922.

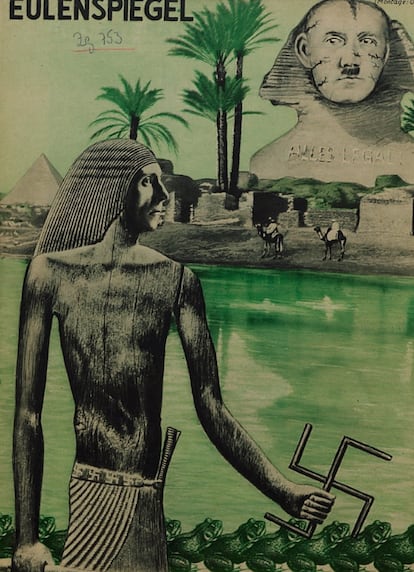

Despite the Indiana Jones movie and despite the fact that Hitler’s idea of an excavation was undoubtedly to be done in uniform and trying to seize something (not unlike invading Poland), the Nazis had very little interest in Ancient Egypt and Egyptology. In fact, the main interest they manifested in Egypt in general was trying to get Rommel’s Panzers up the Nile and seize the Suez Canal. And that was only because they saw the opportunity to destabilize the British Empire in an area that Hitler actually considered the Italians’ natural space, with a “debilitating” climate for the master race. He summed it up by saying: “For us the Egyptian sphinx has no particular interest” (Hitler’s Table Talk, Enigma Books, 2000).

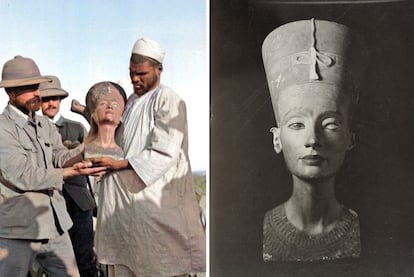

The history of German Egyptology in the Nazi era was marked by the regime’s contempt for all things southern and African, and by the anti-Semitism that led to the marginalization and expulsion of Jewish Egyptologists from universities. Before Hitler came to power, Germany was considered an important place for Egyptological studies, and in fact, celebrities such as James Henry Breasted, who got his degree at the University of Berlin (and, by the way, was one of the inspirations for the character of Indiana Jones), studied in the country. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs financed the German Archaeological Institute (with a branch in Cairo), from which important research was carried out. In the field of Egyptology, Jason Thompson recalls in Wonderful things, a history of egyptology (AUC Press, 2018), personalities such as the linguist and epigrapher Kurt Sethe; Adolf Erman, who collaborated in unveiling the grammar of Egyptian writing; Ludwig Borchardt, who discovered and brought to Germany the famous bust of Nefertiti, or Heinrich Schäfer, with his work that opened new perspectives to understand Egyptian art.

The arrival of the Nazis, which affected this area of studies as it did all areas of life in Germany, meant that historians sympathetic to their ideas, such as Helmunt Berve, professor of ancient history at the University of Leipzig, came to question the very existence of Egyptology as an area of study and encouraged concentrating on that of “peoples similar to us in terms of race and mentality”. Other scholars proposed to align Egyptology with the new requirements of Nazi science. Walther Wolf was one of those who took advantage of the new winds to prosper and gave lectures in the uniform of the SA, so that you did not know if he was going to talk to you about the Third Intermediate Period or sing Tomorrow belongs to me.

Among the Egyptologists who lost their posts (to which must be added those who fell during the war) were Herman Ranke, who had excavated with Borchardt and Herman Junker and had taught in Heidelberg, and Hans Wolfgang Müller, both because they had non-Aryan wives. Paul Ernst Kahle was expelled in Bonn for hiring a Polish Jew as an assistant. Hedwig Jenny Fechheimer-Simon, a pioneer in the study of Egyptian art and its influence on modern sculpture and a member of the acquisitions committee of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, was banned from the museum as a Hebrew and, after trying to escape from Germany, committed suicide with her sister in 1942.

The aforementioned Erman, the great star of German Egyptology at the time, was stripped of his academic positions and honors for having a Jewish grandfather. Another great scholar, Georg Steindorff, founder and director of the Egyptological Institute of Leipzig, escaped in 1939 to the USA with his belongings (which fortunately included his specialized library). Borchardt, as a Jew, watched the rise of the Nazis with horror, but he lived outside Germany during those years (he died in 1938 in Paris); his brother Georg Hermann, a writer, was murdered in Auschwitz in 1943. As for the great Herman Junker, he knew how to read his times and even supported the thesis that the pyramids had actually been built by ancestors of the Germans.

I cannot resist pointing out the relationship of the Nazis with The Mummy, the wonderful original film of 1932. Its director Karl Freund, a Bohemian German who had lived in Berlin since the age of 11, spent the first part of his career in Germany (he was a cameraman with Murnau, Lang and Lubitsch). As a Jew he was lucky enough to go to work in the USA in 1929 but his ex-wife, Susette Liepmannssohn, and his daughter, Gerda, stayed behind. The young woman (see the terrific 90th anniversary book of The Mummy, Notorious, 2023) became involved in anti-Nazi activities and the father went to rescue her in 1937 and managed to take her with him. Susettte, on the other hand, stayed behind and was deported to Ravensbrück, where she died in 1942. The protagonist of The Mummy, the unforgettable Zita Johan, Romanian of German roots (from the Swabians of the Banat), was from a young age obsessed with the American occultist and clairvoyant Edgar Cayce books - who claimed that under the claws of the Sphinx of Gizah there is an “archive of secrets” that holds esoteric knowledge -, which undoubtedly helped the actress create her role of the reincarnated Anck-es-en-Amon, the object of Im-Ho-Tep’s (Boris Karloff) love.

Hitler, as it has been said, had little interest in the history of Ancient Egypt and was not much given to the supernatural stories of mysteries and mummies that are popularly associated with the Pharaonic civilization. The Nazis more inclined to that were Himmler and Rudolph Hess (who in addition had been born in Alexandria and who in the party they called “the yogi of Egypt”, for the yoga). Interested both, Himmler and Hess, in esotericism, occultism and parapsychology, it is easy to imagine the latter dressed as a Jewish priest like Belloq but with his eyebrows protruding from the Mitznefet in the final scene of the opening of the Ark, and the former melting as Gestapo Toht for looking for what he should not. In any case, Himmler was interested in other no less nonsensical things like the Grail, the spear of Longinus or the hammer of Thor but these were not set in Egypt.

Archaeologically, the Nazis preferred to look to the North (Karelia, Swedish Bohuslan, Hedeby) and to the supposed ancient lands of origin of the Aryans that obsessed them, such as Tibet, where Himmler sent the famous expedition led by Ernst Schäfer. The Ahnenerbe (Ancestral Heritage) of the SS and the Amt Rosenberg practiced archaeology à la Nazi, that is to say with ideological and propagandistic purposes and that in general were pure nonsense. Ancient Egypt was a field that did not appeal to the Nazis. Some ideas of that civilization, such as the power of the pharaoh, the military preeminence or the centrality of the State could interest them, but in general the ancient Egyptians were definitely a non-Aryan people and with beliefs, although prior to the detested Judeo-Christianity, too muddled for the National Socialist mentality.

For example, pro-Nazi Egyptologists such as Wolf and Herman Kees, denigrated Akhnaton for possessing traits contrary to the idea of the master race. Akhnaton, however, as Dominic Montserrat explains in the fascinating Akhenatón, historia, fantasía y el Antiguo Egipto (Dilemma 2022), also suffered an attempt of appropriation by some anti-Semitic and neo-pagan sectors that even tried to see an Aryan component in him, stimulated by the Westernized image of the pharaoh built by Egyptologists fascinated with the character such as James Henry Breasted and Arthur Weigall. They liked the purity ingredient of his sun worship and the relationship he established as the spiritual leader of his people.

In fact, Hitler’s devotee, Nazi sympathizer, theosophist and spy Savitri Devi (1905-1982, actually French of Greek origins) contemplated him as a prefiguration of the Führer. But Hitler himself would hardly identify himself with a character like the Pharaoh of Amarna, who interested Freud so much and whose interpretation was so significant for the history of psychoanalysis. Not to mention the grotesque aspect of his representations. Adolf Hitler was more of an admiror of Emperor Barbarossa Hohenstaufen and Frederick the Great.

However, the Nazi leader was an unexpected fan of the bust of Nefertiti. When Goering and other Reich leaders argued in favor of returning the sculpture to Egypt to improve relations, Hitler came out swinging, stating flatly that “what the German people have, they keep” (fortunately Indy swiped the Ark from him). He said he had seen the bust many times and always marveled at it, and that one of his dreams was to install Nefertiti in a new Egyptian museum in Berlin with a room under a large vault just for her. It is curious to think that he would like the way it is now.

Hitler was never in Egypt, but Joseph Goebbels was. He made a famous whirlwind trip to the country of the Nile in 1939, five months before the outbreak of World War II. The Propaganda Minister arrived at Cairo airport on April 6 aboard a Focke-Wulf Condor from Rhodes, where he was on vacation. The visit, labeled as private, provoked the enthusiasm of the German colony and made the British quite nervous, not to mention the Jews living in Egypt. Goebbels stayed at the Mena House, offered a reception at the German House in Boulak and a meal at the delegation of his country and, in what concerns us, visited the pyramids of Giza, the necropolis of Saqqara and the Egyptian Museum -apart from visiting, like any tourist, the markets of Khan al-Khalili, where he bought several things for his wife Magda (surely to get forgiven after so many affairs with actresses).

During the visit to the Great Pyramid he expressed (according to the press reports of the time) to his guide the aforementioned famous professor Herman Junker, then director of the Deutsches Institut, his deep admiration for the civilization of Ancient Egypt, and he did it again before the golden objects of the tomb of Tutankhamun in the museum of Cairo. He even starred in an exalted moonlit camel ride through the pyramids (something Hitler would have disapproved of, who praised Rommel for not succumbing to the temptation to get on a dromedary and thus avoid the unseemly picturesque photo: the Marshal was always supposed to ride in an armored car). Goebbels, however, did not show the same enthusiasm for Ancient Egypt as he did when he visited Greece in 1936 (Athens, Delphi, and various excavations) and admired the great achievements of the Greeks (at the Acropolis he felt he was at one of “the noblest sites of Nordic art”). In Egypt he even compared negatively the “useless” effort of building the pyramids or the Sphinx with the “socially profitable” construction of the highways of Hitler’s Third Reich or the functionality of the New Chancellery designed by Speer.

One last curious detail: one of the characters who confronted Hitler and of whom it is said that he was a real black beast for the Nazi leader was an Egyptologist, the Englishman John Pendlebury, who had been director of the excavations in Amarna and then was appointed vice-consul in Crete as a cover for his work in military intelligence to face the Nazi invasion of the island, during which he was shot by German paratroopers.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.