‘Marxists are brainwashing us’: The conspiracy theory taking hold among some on the right

The far right is promoting the theory that large companies, governments, and political parties of almost every stripe have surrendered to cultural Marxism in their feminist, LGBT+ and environmentalist components

In 2011, when far-right terrorist Anders Breivik murdered 77 people – the majority of whom were young Norwegian Labor Party members – in the massacre on Norway’s Utoya island, he justified his actions as part of the fight against Muslim and Marxist attacks on the West. His thinking (if one wants to call it that) subscribed to the theory of cultural Marxism, according to which feminism, the LGBT+ movement, environmentalism, atheism, multiculturalism and so on are working together to destroy the free world. These elements have allegedly managed to inject the fatal virus of “political correctness” into society, corroding it and leading us toward a totalitarian future. Marxism continues to be a specter that haunts the world, now hidden in new forms. Breivik claimed to be fighting against it.

Popular with the far right and alternative right, cultural Marxism is a conspiracy theory that contends that the left, incapable of winning in the political and economic realms, has inserted itself into everything else to triumph in the cultural domain (here, the term refers to culture in the broad sense, not just cultural products). Under this theory, progressive ideas permeate society as a whole, and the latter is victim to mass brainwashing. “We are not going to back down from this cultural and Jewish Marxist brainwashing we’ve been indoctrinated with to become useful idiots for the systems of international finance, capitalism and war… We simply want to defend working-class whites, our rights, and our nation,” US alt-right agitator Mike Enoch declared at a rally.

As with all stories of this type, there are different variations, but the following one is quite descriptive: it all began after the Russian Revolution when the Soviet model failed to spread to other countries. Philosopher Antonio Gramsci argued that it was necessary to achieve cultural hegemony, that is, to dominate the landscape of thought, art, education, media, common sense, beliefs, and morals. If Marx had established how important it was to transform the economic base and that the “superstructure”-where society’s cultural elements are located - depended on it, the Italian theorist turned that theory upside down by including culture as another equally important battlefield.

The Frankfurt School philosophers (Adorno, Horkheimer, and Marcuse, who synthesized Freud and Marx), the New Left, and the countercultural movements of the 1960s followed in Gramsci’s footsteps. As a consequence, believers say, minorities and identity groups have come to conspire against capitalism, Christianity, the traditional family, and the free market; they have managed to silence dissent through the so-called muzzle of “political correctness.” All of this supposedly represents a successful translation of Marx’s thesis to the cultural field: the aforementioned minorities would replace the working class as agents of revolution, and indoctrination would occur largely through universities infiltrated by these ideas. Large companies, governments, and political parties of almost every stripe have allegedly accepted cultural Marxism in their environmentalist, LGBT+ and feminist manifestations.

“This theory frames the ideological rearmament of the far right, which, since the late 1990s – first in the United States and then in Europe – has decided to stake everything on the culture wars. In their absurd simplicity, conspiracy theories offer an interpretation of the world where everything seems to fit. That’s why they’re successful,” says Italian historian Steven Forti. A suggestive story is an effective way to make far-right ideas go viral against a spectral and fearsome enemy. In Spain, the leaders of the far right party Vox’ have referred directly to these ideas. National party chief Santiago Abascal has occasionally pointed out the “urgent need to curb cultural Marxism.” Similarly, though not quite as explicitly, Madrid regional chief Isabel Díaz Ayuso, of Spain’s mainstream conservative Popular Party (PP), was successful with her resonant slogan, “communism or freedom.” In his book La vuelta del comunismo (or The Return of Communism), the well-known right-wing Spanish journalist Federico Jiménez Losantos warns of this threat and associates queer theory-allied feminism with the alleged return of communism. These theories tend to see crypto-communists ready to destroy freedom everywhere.

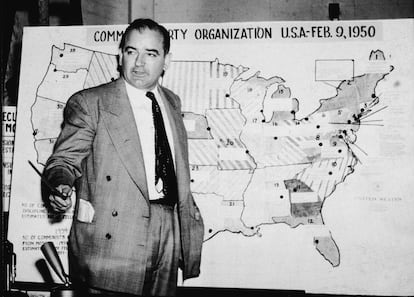

Some see traces of similar logic in earlier currents. “As in Judeo-Bolshevism, cultural Marxism homogenizes vast groups of shadowy enemies and assigns them a secret design to upend society,” Yale University Professor Samuel Moyn writes in the New York Times. The Hollywood Red Scare, provoked by Senator Joseph McCarthy, and the subsequent witch hunts followed a similar pattern.

These days, in certain quarters (most notably, on social media), even climate change is seen as a hoax to justify installing a “green dictatorship.” Of course, conspiracy theorists’ “favorite” businessman, George Soros, is usually in the mix. “When Santiago Abascal talks about a ‘progressive dictatorship’ or Donald Trump mentions ‘a dictatorship of political correctness,’ they are largely talking about the same thing,” Forti points out. Curiously, on the left, rather than feeling that they have surreptitiously dominated the world, the opposite sensation prevails: the sense of constant defeat and an uncertain future amidst capitalism that’s stronger and more deregulated than ever.

Grains of truth

Actually, the theory of cultural Marxism contains a grain of truth, which is why many people find it credible. Indeed, since Gramsci and the Frankfurt School, through counterculture and the New Left, the left has increasingly emphasized cultural and identity issues. Nevertheless, “we’re dealing with a conspiracy theory because it takes some real trends - the fact that the left lost influence in a changing working class – to create a story about the coordinated infiltration of institutions. It is the idea that there’s an army of moles undermining Western culture,” says Argentine historian Pablo Stefanoni, the author of ¿La rebeldía se volvió de derecha? (or Has Rebellion Become Right-Wing?. As Stefanoni notes, many of the dynamics attributed to cultural Marxism (the de-structuring of the family, the waning influence of religion, the mixing of cultures and so on) stem from the dynamics of post-industrial capitalism itself.

Other far-right conspiracy theories also take small grains of truth to create an absurd story. For example, the “great replacement” theory, advanced by Frenchman Renaud Camus, uses the challenge of migration to invent a worldwide conspiracy of “globalist elites” who intend to replace Western civilization with Islamic civilization… in just one generation. Generally, this type of thought attributes bad intentions to certain political and social trends in order to delegitimize them. The critics of so-called cultural Marxism are trying to revive the Cold War’s anti-Communist fervor at a time when communism practically no longer exists. “It’s a sort of zombie anti-Communism that fosters a sense of existential threat and combines ideological proposals, demographic and cultural changes, and socioeconomic processes with distinct and heterogeneous sources under the same demonizing label,” Stefanoni concludes.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.