Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat reconcile in Paris

The father of pop art and the prodigy of the neo-expressionist movement jointly created around 160 paintings and photographs. An exhibit at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris is now celebrating the 40th anniversary of this collaboration

There couldn’t have been two more different American artists. On one hand, there was the pop art genius – the 50-something son of Slovak immigrants who captured the zeitgeist of the 1960s. And, on the other, the 20-something child of a Haitian and a Puerto Rican, who became the king of street art in the 1980s.

Andy Warhol (1928-1987) was a renowned artist, who ruled the counterculture for more than two decades out of his art studio – The Factory – in New York City. Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), meanwhile, was the rising star of the vibrant and chaotic Big Apple in the 1980s.

In October of 1983, the two men met. Subsequently, over the course of two years – between 1983 and 1985 – they collaborated on around 160 paintings and photographs. In the words of fellow artist Keith Haring, these works were made because “two extraordinary spirits fused to create a third spirit… unique and totally different.” A miracle had taken place.

“It’s one of the most exciting stories in the history of art: how it started, how intense it was, how it ended,” summarizes Dieter Buchhart, the curator of the Basquiat and Warhol exhibition, Painting with Four Hands, which can be seen until August 28 at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris.

Suzanne Pagé – director of the foundation – reminds us that “although he was exhibited everywhere, Warhol was very shy. And Basquiat was someone who totally preserved his mystery. Each man also revealed little to the other. This is why [their collaboration] is so fascinating.”

“It’s unique that two artists of [such a high] level collaborated in a way that. In many paintings in the exhibition, you cannot tell who did what,” notes Jean-Paul Claverie, artistic advisor to Bernard Arnault – the president of the foundation and the richest man in the world. “Warhol and Basquiat perform their works on canvas with four hands, as if they were pianists.”

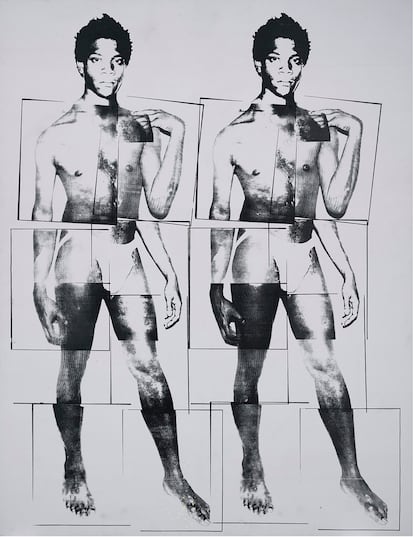

The numbers of the exhibition – held in the Frank Gehry building in the Bois de Boulogne park in Paris – are overwhelming: 11 galleries, 4 floors, 80 joint canvases, plus works by other artists of the time, along with the iconic photographs by Michael Halsband, which show Basquiat and Warhol dressed as boxers. A few days before the opening, on April 5, EL PAÍS spoke with Buchhart, Pagé and Claverie – the creators of one of the cultural events of the year.

The idea, says Claverie, arose in 2018, when the Basquiat retrospective opened at the Louis Vuitton Foundation. The inauguration was attended by gallery owner Bruno Bischofberger – the man who organized the meeting between Warhol and Basquiat. Bischofberger told Claverie about the genesis of that collaboration, leading to the idea that the Basquiat exhibit in Paris required a second part: what would become Painting with Four Hands.

“Mr. Arnault was immediately very enthusiastic,” recalls the advisor to the luxury magnate, who owns several of the paintings that can be viewed over the next few months in Paris. Another thirty-or-so come from the Bischofberger collection. “It was exciting working with him, collecting his testimony, his memory,” says Claverie.

Basquiat and Warhol followed a tradition in art history: that of collective works. “I see a difference between a Rubens collaboration with his team and two individual artists who – during a particular moment in history – meet and work together, while simultaneously creating their own works,” Buchhart opines. “But it’s interesting that literally, when Basquiat was in town, he would meet Warhol at The Factory from 9am to 5pm. Then, they would go to dinner, or a party, or an exhibition. It was a very serious conversation. Warhol and Basquiat were not a unit, but a remix of two styles.”

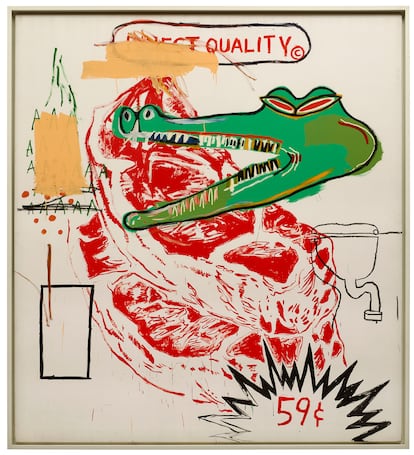

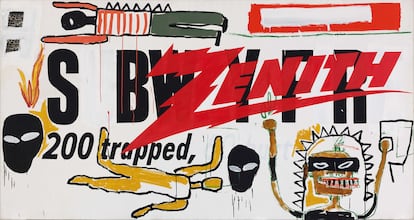

The idea of remixing – like that of hip hop, jazz, or the fusion of European and African music – runs through the exhibition, almost like a soundtrack. Multinational advertisements or tabloid headlines – Warhol’s trademarks – are mixed with Basquiat’s graffiti and text as art. Basquiat said of Warhol: “He started most of the paintings. He would put something very concrete or very recognizable on them – like a newspaper tab or a product logo – and then I would deface it in some way and then try to get him to rework it a little bit. Then, I would rework it again.” Warhol, in his diaries, wrote: “I think the pictures we do together come out best when it’s impossible to tell who did what.”

“What connected them was the energy… a bit like a table tennis match. One would say ‘this’ visually, and the other would react visually. They challenged each other. The challenge elevated what they did,” affirms Buchhart, who has spent half his life studying Basquiat and has never gotten bored with him. “Every time I see a painting of his, I feel like he infuses me with new energy.”

The climax of the relationship was also what caused the distance between the two artists: the joint exhibition at the Tony Shafrazi gallery in New York. The famous photographs of Basquiat and Warhol as boxers were the center of the event… but they received devastating reviews. The one from The New York Times was decisive for the end of this collaboration: “A year ago, I wrote that Jean-Michel Basquiat had a chance to become a very good painter… provided he did not succumb to the forces that want to make him a mascot of the art world,” wrote art critic Vivien Raynor. “This year,” she added, referring to the exhibition, “it seems that these forces have prevailed.”

In the Louis Vuitton catalogue, Bischofberger writes: “Basquiat – who had hoped to gain notoriety thanks to this exhibition and consecration thanks to the famous Warhol – was disappointed by the critical reaction and practically decided to end the painting sessions at The Factory.” Warhol would die in February of 1987 after an operation. Basquiat, in August of 1988, from an overdose.

Post-mortem, there were even more ruthless critics, such as Robert Hughes: “[Basquiat’s] ‘importance’ was merely that of a symptom; it signifies little more than the hysteria of instant reputation that still so grotesquely afflicts American taste. His admirers are like a posse of right-to-lifers, adoring the fetus of a talent and rhapsodizing about what a great man it might have become if only it had lived.”

Hughes, in the same article, called the work of Warhol and Basquiat as being made up of “worthless collaborative paintings.” The article – alluding to the 1985 exhibition – was titled Requiem for a Featherweight.

Later, there were films dedicated to the friendship between the two artists, as well as books and exhibitions that magnified the myth. The electricity of this collaboration – that of the characters involved, their legend and the paintings – continues to buzz.

“Today, 40 years later, they’re still very modern,” Claverie opines. “They’re symbols of [a kind of] art that comes down to the street; of diverse forms of expression linked, at the same time, to the visual arts, to music, to the graphic arts, to the art present in the city and in our daily life. It’s not sacred art.”

Today, Pagé sees “an echo of the language of painting completely electrified by that collaboration: painting is redisplayed, once again, on the walls in the street. For a while, it had disappeared in favor of a more conceptual language – video, installations, performances. And suddenly, there’s a revival of the painting.” There are now paintings, he adds, that speak to today’s world: “Everything that has to do with racism, violence, urban imagery... all of this is present today.”

Basquiat and Warhol have won the battle of time… or, in any case, that of the public and the market. The exhibition in Paris is irrefutable proof of this.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.