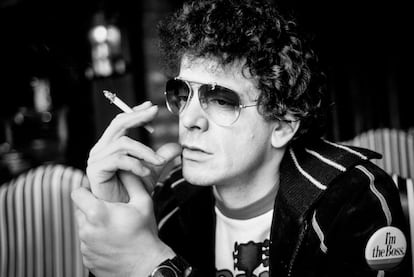

Fifty years of Lou Reed’s ‘Transformer’: Life without the wild side is not worth living

One of the most unorthodox, dazzling and wild albums in the history of pop music marks half a century

Lou Reed’s music continues to play around the world. This November marks the 50th anniversary of the release of one of the most unorthodox, dazzling and wild records in the history of pop music, Transformer. Released in 1972, the album elevated Lou Reed to rock and roll stardom – not thanks to music critics, but rather the public.

In the complex world of our New York rocker’s music and poetry, Transformer marked the beginning of a career unlike that of any other rock musician. Transformer was completely different. Its success was a miracle. It was the first time the classic song Walk on the Wild Side was recorded. The track was released as a single and climbed the bestseller lists. The song’s success is thanks to David Bowie. In 1972, the lyrics of Walk on the Wild Side were understood by very few people, but it didn’t matter: the song got into your head, and you couldn’t forget it. It played on the radio, but few knew that the song’s characters were real. They were the people who hung out at Andy Warhol’s Factory, where the artistic avant-garde explored their sexuality. That is Transformer: a hymn to sexual promiscuity and freedom. The men became women and the women became men, and they did so with unbridled joy.

This record created Lou Reed’s voice. It wouldn’t sound the way it does without two wizards of acoustic invention, Mick Ronson and David Bowie, who produced the album and thereby invented that voice. Lou Reed’s voice never sounded live the way it does on this vinyl from 1972. In that sense, the record was also conceptual art: its sound could only be heard on a record player. In my opinion, that is this album’s great achievement: a sound that began with rock and roll and reached unknown worlds. My great disappointment when I first heard Lou Reed live in Madrid, 40 years ago, was that Walk on the Wild Side did not sound like it does on Transformer. It would never sound like that, because that voice was an artificial creation. That voice was a utopia.

Another of the great songs on the album is Perfect Day, a melancholic hymn to the placidity of a walk in Central Park. We never knew if it spoke of love for a human being, or love for shooting up heroin, or maybe both. It doesn’t matter, because the song is exceptional. One of the critics’ big mistakes was classifying Transformer as glam rock, a disastrous label. This album is literary. The title alone evokes Franz Kafka’s novel. It is not a decadent record, nor a record of gay pride, nor a hymn to transvestism. It is pure beauty, free sound. It is the creation of a voice that claims its right to exist for itself, for its mystery, for its vocal clarity, for its simplicity. The song Andy’s Chest, dedicated to Warhol, is an almost dreamlike poem inspired by actress Valerie Solanas’s assassination attempt on the painter.

In Transformer, Lou Reed elevated rock to a form of literature. There is more poetry on this record than in a thousand books together. It is a miracle of modernity. The album expresses the lasting essence of New York City, combining rock with ancient forms of literature and poetry. This is an infinite recording. The album is the birth of a nation of free minds. Everyone who heard it in 1972 became someone else and took a walk on the wild side of life, because without the wild side, life is not worth living. The message still stands. And it continues to be revolutionary, provocative, anti-bourgeois, anti-capitalist and anti-communist, nihilist and vitalist at the same time. It is liberating, romantic, sordid and utopian all at once. It has a recalcitrant individualism. When it appeared, Transformer was a cry of beauty. And that cry remains with us today.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.