The long and fierce struggle of the Apaches

Historian Paul Andrew Hutton tells the story of 50 years of war, savagery and adventure on the final frontier of the American West

In his 2016 epic chronicle The Apache Wars (now out in a Spanish edition by the publishing house Desperta Ferro), renowned historian Paul Andrew Hutton takes his readers on a horseback ride through the heart of what the Mexicans, and the Spanish before them, had named Apacheria — the region inhabited by the Apache people extending from the Arkansas River into what are now the northern states of Mexico, and from central Texas through New Mexico to central Arizona. Flanked by bands of hardened, elusive Mescalero and Chiricuaha warriors, you cross the Rio Grande and into the fearsome Sierra del Diablo range. As you turn the pages, your heart races with excitement and anticipation, drawn into the untamed world of fierce warriors and breathtaking landscapes. You vividly imagine the harsh territory, with its barren and hostile land of rugged mountains and unforgiving deserts. Every pass, rock, and cactus seems to hide some danger, whether an arrow, Winchester or rifle bullet or something even worse. “It was not good to be taken captive by the Apaches,” Hutton writes, conjuring up images of Ulzana’s Raid, Robert Aldrich’s 1972 film that depicted the wisdom of keeping one last bullet for yourself when fighting the Apaches.

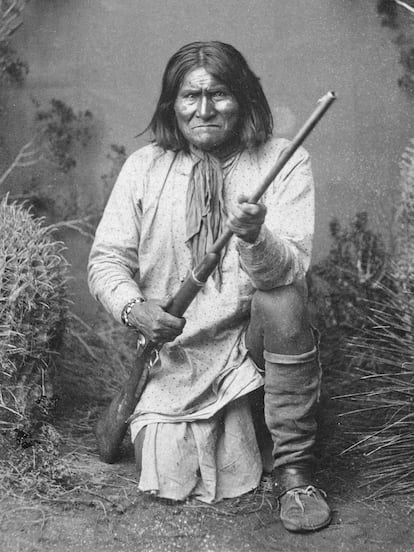

We are in the lands of the great chiefs — Mangas Coloradas, Cochise and Geronimo — in the world of Fort Apache, Apache Pass and stagecoach attacks. We meet fabled frontiersman Kit Carson and Indian hunters army generals like Crook and Miles who chase an enemy that is always vanishing into thin air — “If you saw them, sir, they were not Apaches.” It’s the story of the longest war ever waged by the United States, a savage war without quarter — “When you get them together, kill all the grown Indians and take the children prisoners and sell them to defray the expense of killing the Indians.” It was a savage war in a deadly landscape known to the outside world as Apacheria, where “every plant bore a barb, every insect a stinger, every bird a talon, every reptile a fang.”

Hutton’s work is an impressive contribution to the Apache canon that includes Once They Moved Like The Wind by David Roberts (1994); The Apaches: Eagles of the Southwest by D. E. Worcester (1992); Geronimo’s Story of His Life, as told to S.M. Barrett (1906); and, of course, the Blueberry comic book series that chronicles the adventures of Mike Steve Donovan (alias Blueberry) on his travels through the Old West. Hutton painstakingly charts the protracted history of the brutal conflict pitting the uncompromising indigenous nation against the Spanish, Mexicans and Americans, culminating in a genocidal war. The book is dotted with colorful details worthy of John Ford, such as “Nantan Eclatten,” the derogatory name meaning “a raw and virgin lieutenant” given by Apaches to greenhorn soldiers.

The 73-year-old scholar, born in Frankfurt and adopted by an American family from a U.S. military base, is a history professor at the University of New Mexico and former director of the Western History Association. Hutton’s book examines the intricate history of repeated Apache raids and subsequent retaliations, in which a kidnapping takes center stage. This half-century of conflict was marked by acts of treachery, revenge and forced relocations to inhospitable reservations governed by corrupt officials. In 1861, a young white boy named Felix Ward, who would later be known as Mickey Free, was taken by Aravaipa Apaches during a raid on his family’s ranch. The abduction set into motion a series of events that would ultimately shape the destiny of the Apache lands.

“The story of Mickey Free has always intrigued me,” writes Hutton. A character caught between two worlds and cultures, he lived in a perpetual state of conflict, alienation and identity crisis. Even though he was raised as an Apache, nobody in either world fully trusted Mickey Free. But both sides needed him as a guide, explorer, and interpreter for the U.S. Army. As a European orphan raised in the United States, Hutton identifies with the drama in Mickey Free’s soul. The Chiricahuas considered Free a nuisance and blamed him for triggering Cochise’s killing spree that slaughtered 150 people in two months. The U.S. Army also despised Free. Its Chief of Scouts, Al Sieber, once described him as “half-Mexican, half-Irish, and whole son of a bitch.”

Tales of savagery

Both sides were brutal and ferocious, but as David Roberts noted before him, the Apaches were especially cruel. Hutton describes how they skinned and roasted white captives alive, and killed small children by smashing their heads against a stone. “The Apaches were raiders, pillagers and plunderers – New World Vikings. They were particularly feared in war and notorious for their fiendish torture of prisoners. They highly valued anyone with the imagination to devise excruciating ordeals. You really wished you had that last bullet, as they were wont to say on the frontier. Captives who displayed courage under torture were highly regarded by the Apaches. The Americans were just as ruthless — after killing Mangas Coloradas, his head was cut off and mounted for public display. Everyone in my book — Spaniards, Mexicans, Apaches, Americans — was capable of great cruelty. While it’s true Apaches seemed to have a cultural predisposition to cruelty, there was much hypocrisy among the Americans who claimed to be civilized while engaging in tremendous barbarism. It was all quite medieval.”

Were the Apaches as tough as they were portrayed? Hutton writes that Crook called the Apaches “the tigers of the human race.” They were incredibly rugged warriors and could outrun a cavalry on foot. They could put seven arrows in the air before the first one hit the ground. They knew the terrain and how to use it to their advantage. Their incredible mobility made them masters of what today we call guerrilla warfare. Of course, the memoirs of American soldiers sometimes exaggerated their prowess so their own victories would seem more impressive. The Apaches were fewer in number than the Plains Indians to the north, which made them more reluctant to risk their lives unnecessarily. Although they valued horses highly, they did not hesitate to eat them in a pinch. “Never before in the history of America,” writes Hutton , “had so many tried to kill so few.”

Hutton doesn’t just explain the facts and details of the Apache wars, he also takes us into the Apache mentality. They were very individualistic, but also felt great solidarity with their own, which explains the success of the Apache police. Hutton notes their affinity for mescal (hence the name of the Mescalero tribe), their respect for bears, the significance of the female puberty ceremony, their obsession with gambling, and the curious fact that they never ate fish. They could not abide being confined. Three facets seemed to condition Apache culture: plunder, revenge (and honor) and superstition (and taboos). “They were a people steeped in superstition. They believed in witches, curses and especially ghosts. It was a great taboo for them to touch the dead, so they rarely scalped corpses. Unlike other Indians, especially the tribes of the Great Plains, they did not keep scalps as war trophies.”

White people, on the other hand, scalped Indians with relish. “I was surprised at the scale of the practice, especially by American bounty hunters who were paid for every Indian scalp. American Indians — though not the Apaches — practiced scalping before the white man arrived, but the Europeans turned the ritual practice into a gruesome business. Their scalps often included ears, and sometimes the whole heads were cut off.

There is a Chiricahua woman in The Apache Wars, a woman named Lozen — the sister of Victorio — who handled the rifle and knife as well as any man. Were there many women warriors in the Apache world? How were Apache women generally treated? Not very well, says Hutton. Infidelity was punished by severing noses or even death. “Lozen was truly remarkable. She was noted, like her brother Victorio, for her wisdom and her courage, sometimes fighting alongside him in battle, but it was her spiritual power that set her apart from all others. Some historians like Bob Utley and Ed Sweeney have dismissed stories about her as fantasies, but Apaches — then and now — believed in her great powers.”

Who was the best Apache chief? Hutton doesn’t care much for Geronimo and his brutality, such as the time Geronimo wanted to kill the tribe’s babies so their cries wouldn’t give their position away. “I think Cochise was the greatest Apache leader, followed by Mangas Coloradas, and then Victorio. Geronimo was always looking out for himself and not the Apache people. He could be a bully and a murderer, but of course he was also a great warrior. His own people eventually turned against him, and his actions led to the forced relocation of all Arizona Apaches. It’s ironic that he became, perhaps, the best known Indian in history.” One of Hutton’s favorite stories about the Apache wars is the friendship between Tom Jeffords and Cochise, and how that relationship brought about a brief peace. “It was the basis for one of my favorite novels — Blood Brother by Elliott Arnold — which was made into the film called Broken Arrow.”

What are some of the best films about Apaches and how has Hollywood treated famous Apaches like Cochise, Geronimo, Massai and Chato? Was the real Ulzana like the one in Aldrich’s movie? “Broken Arrow is my favorite,” said Hutton, “and I also very much like John Ford’s films about the U.S. Cavalry like Fort Apache and Rio Grande. Another of my favorites is Ulzana’s Raid because I find it very realistic. Before that movie, Aldrich and [Burt] Lancaster had made Apache about Massai, the famous renegade, which is based on a novel by Paul Wellman. As you can see, I’m a big fan of western movies.” Hutton was even the historical advisor on The Missing, the 2003 Western film directed by Ron Howard. “The Missing was a great experience, and director Ron Howard is as nice as everyone says. My son and I have a brief cameo in the village scene. The witch doctor is not based on a real character, but on the Apache belief in witchcraft. I had them use owls in the film as a symbol of the evil, reincarnated spirits of wicked people, which is what the Apaches believed. Howard also had some Apache advisors.”

Regarding Apache life today, Hutton said, “Like many tribes, the Apache often live in poverty and alcoholism is still a problem. The various Apache reservations in Arizona, New Mexico and Oklahoma strive to keep their history and traditions alive. Some, like the Mescalero and White Mountain tribes, have benefited greatly from gambling and casinos. One of my proudest moments was when an elderly Jicarilla woman told me how much she enjoyed my book and asked me to dedicate it to her. I hope I have done justice to the Apaches in the book.”

One of the finest pop culture representations of Apaches was the Franco-Belgian Blueberry comic book series created by the Belgian scriptwriter Jean-Michel Charlier and French comics artist Jean Giraud. Surprisingly, Hutton is familiar with the comics. “I collected them over the years and think I have almost every one. Mickey Free even appears in one of the later issues. The Europeans have always done better Western comics than the Americans.”

Paul Andrew Hutton is the editor of The Custer Reader, an indispensable compendium of articles about the controversial general. “Custer is still a great hero to me. When I was a kid, I saw Errol Flynn play Custer in They Died With Their Boots On and I was hooked. He’s such a fascinating and contradictory character – larger than life. I think his last stand at Little Bighorn is the most epic moment in the history of the American West. He’s often portrayed now as a villain, which isn’t true. His illustrious role in the Civil War has been forgotten and he’s portrayed as a genocidal Indian hater. This is just bad history — I blame it on popular culture and ignorance. I’m going to the Little Bighorn battlefield site in June — it’s an eerie, haunted place. Years ago, I was appointed to the commission that chose the design for the Indian monument that now stands on the site. Custer and Sitting Bull are going to be major characters in a new book I’m writing called The Unknown Country, which I hope to finish this fall.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.