A Jewish couple dodged Nazi censorship to publish children’s books in occupied Holland

The El Pintor collection gets fresh life from a new biography and an upcoming exhibit at the National Holocaust Museum in Amsterdam

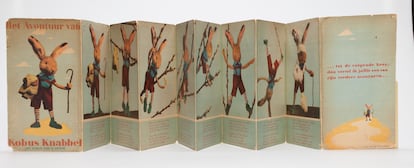

During the German occupation of the Netherlands from 1941 to 1944, a collection of children’s books and games published under the pen name of El Pintor [The Painter] enriched the lives of thousands of Dutch children. The publisher made print runs of 10,000 for the local market and up to 60,000 translated versions for Germany. Behind the El Pintor pseudonym is a Jewish couple’s remarkable story of courage and conviction: Galinka Ehrenfest and her husband, Jaap Kloot. They used the Spanish pseudonym to obscure their heritage, fund Dutch resistance efforts and help Jews who were hiding from the Nazi regime. A collection of El Pintor’s books was recently purchased at the 2023 New York International Antiquarian Book Fair by a private buyer who intends to donate them to the National Holocaust Museum in Amsterdam.

World War II eventually destroyed the magical universe created by El Pintor. When he was only 26, Jaap Kloot was murdered in 1943 at the Sobibor extermination camp in German-occupied Poland. Galinka Ehrenfest survived the war but miscarried their only child. “It’s very sad to think that someone who brightened children’s lives and whose work was valued and translated by German occupiers later perished at their hands,” said Peter Kraus, the owner of Ursus Rare Books in New York, who sold the collection.

Kraus is a longtime exhibitor at TEFAF Maastricht (the Netherlands), widely regarded as the world’s premier fair for fine art, antiques and design. At the 2023 fair, a visitor approached Kraus and asked for his business card. “I often sell illustrated books, and this Dutch collector asked me if I would like to sell a collection he had been building for over 30 years. So I cataloged this one-of-a-kind collection,” said Kraus. The buyer is a Dutch citizen who prefers to remain anonymous. “These books are remarkable for their quality. The printing is very good, and the foldouts are extraordinary. To think it was all done in the middle of the war with scarce materials and all sorts of obstacles — I don’t know of anything like it.”

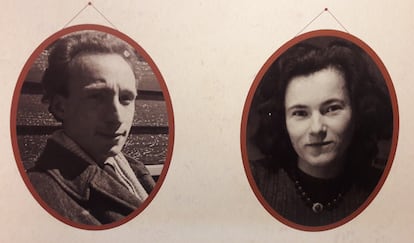

Galinka Ehrenfest and Jaap Kloot met in 1934 at the New School of Art in Amsterdam. Her father, Paul Ehrenfest, was an Austrian-born physicist, and her mother, Tatiana Afanassjeva, was a Russian mathematician. Galinka was born in 1910 in what is now Estonia, and moved to the Dutch city of Leiden when her father became a professor there. Jaap Kloot was born in 1916, and his father was a merchant. The two became friends and formed a circle of artists who later collaborated on books by El Pintor. Kloot started a company called Corunda that would publish 17 books by El Pintor illustrated in color and full of wild animals, exotic landscapes and outdoor games that helped children cope with the grim reality of war. “I had written a book about two Jewish artists, and during my research I saw a painting by Galinka,” said Linda Horn, who wrote a book published in the Netherlands about Ehrenfest’s life. “It interested me, and as I continued my research, I remembered the books by El Pintor I had when I was a child.”

The books and games created by Ehrenfest and Kloot were very successful, writes Horn, “and their determination was commendable. They carried on despite Nazi laws that seized their company.” Occupied by German troops from 1940 to 1945, it was a struggle in the Netherlands to find paper and circumvent Nazi censorship. “There were many regulations imposed by the occupiers, and they could only publish after obtaining approval. But they did it — telling the story of publishing children’s books under those conditions was gratifying,” said Horn. She said that after publishing her book on Ehrenfest, many people called “from the antiquarian book trade, but also from others who said they still had copies in their homes and didn’t know they were so special.” It’s unusual for children’s books to survive so long in good condition.

Galinka Ehrenfest’s family was very close to Albert Einstein, who once gave her a violin as a child. The relationship was so close that she and her siblings (two brothers and a sister) called him by his surname, like they do with uncles. One of Galinka’s brothers had Down syndrome, while her other siblings were gifted. Galinka discovered an aptitude for art and music, and sought that path. She traveled alone to the United States and studied at an art school in Los Angeles on a scholarship. “She also visited her father, who was teaching in California,” writes Horn. “One day she found what she was looking for — working with children. She designed playgrounds and games for little ones to play and be mischievous.” El Pintor’s whimsical stories are full of children holding on to balloons as they fly through the air, frogs gathering at the water’s edge and rabbits snacking in the park. Children could build cardboard towns with cut-outs of stately buildings along Amsterdam’s canals, bridges, trees, trucks and horse-drawn carriages. There are gardens where the fairies are little girls and pop-ups to delight children experiencing the hardships of war.

In 1941, when the Nazis seized businesses from the Jews, Jaap Kloot handed over Corunda to people he trusted and continued working discreetly. He and Galinka took charge of finding hiding places for persecuted Jews. Although they spent most nights in different places to avoid detection, Kloot was arrested in May 1943 and died two months later. On June 19, a pregnant Ehrenfest was arrested and interrogated in jail for a week. According to documents in the Amsterdam Resistance Museum, “an SS captain named Benno Samel coached her and others on how to respond to the interrogations,” which enabled her to craft a credible story that led to her release on June 26. Her baby with Kloot was stillborn shortly thereafter. Ehrenfest somehow got her name removed from the registry of Dutch Jews, but Kloot’s parents and four of his eight siblings died in the extermination camps.

Tragedy had struck Galinka’s family even before World War II. “Her father experienced professional difficulties in 1933, and foreseeing Germany’s future [Hitler came to power that same year], he got a gun and killed his son with Down syndrome before committing suicide,” said Linda Horn. Carefully choosing her words, Horn said, “He may have felt defeated, and fearing the Nazis, maybe he thought the boy had no future.”

Galinka Ehrenfest, who died at 69, published one more book in El Pintor collection. After the war, she became an interior designer specializing in children’s rooms. “She created spaces for children to build things and take them apart,” said Horn, “spaces for them to turn their imaginations into reality and where they could learn without interference from grownups.” With Horn’s biography and the upcoming book collection exhibit, the magic of El Pintor is once again in the public eye.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.