From Einstein and Freud to Spielberg and Roth: the influence of Jewish culture on the world

The work of artists and intellectuals whose background was previously considered irrelevant or accidental is now being examined in a new light

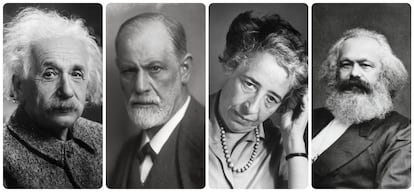

It’s a debate that has been going on for more than a century, but which built up steam in 1919 when American sociologist Thorstein Veblen published The Intellectual Pre-eminence of Jews in Modern Europe. In this academic essay, Veblen discussed the now commonplace and statistically supported notion that many of the transformative developments in Western culture are the handiwork of some very talented Jewish people. Without Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Gustav Mahler, Franz Kafka, Albert Einstein or Hannah Arendt, politics, psychology, music, literature, science and philosophy would be very different. The list of Nobel Prize winners provides a statistical measure – almost a quarter of all Nobel laureates are of Jewish descent. The world’s Jewish population numbers around 13 million, seven million of which live in Israel and five million in the United States. Since Jews only represent 0.16% of the global population, no other group can match the rate of Jewish Nobel laureates per 1,000 inhabitants.

This bold fact has inspired reflection and theories over the years and begs the question as to whether it holds true today. Are Jews still the chosen people, at least as far as culture and science are concerned? The current debate is not so much about whether Jews have shaped the modern world, but whether their influence is still outsized and transformative. Scholars of Jewish culture generally agree that it shone brightly in Europe between 1750 and 1950, the period called Modern Judaism. But since the mid-20th century, perspectives have been clouded by the memory of the Holocaust, the creation of the state of Israel and the shrinking Jewish communities of Europe. These days, the only numerous and influential Jewish communities are in France, and they are getting smaller and smaller in the United Kingdom.

It must be noted that the term “Jewish” is not an ethnic or religious descriptor, but applies to anyone with that cultural heritage or who self-identifies as such. In fact, many of the most influential Jews like Marx, Einstein and Freud were atheists and even disavowed their family tradition. However, Norman Lebrecht, the author of Genius and Anxiety: How the Jews Changed the World, 1847-1947, argues that their work exhibits intrinsically Jewish traits that were certainly home-nurtured, which is where the most deep-seated and enduring cultural characteristics are passed on to new generations.

Lebrecht writes that Einstein’s sardonic aphorisms are unmistakably Hebraic, and that Freud’s psychoanalytic theory employs six of the 13 principles of Talmudic exegesis, despite growing up in a secular environment without any religious education. Lebrecht argues in somewhat Freudian terms that the inventor of psychoanalysis thought like a rabbi, but it was unconscious, as if absorbed through some sort of cultural osmosis, much like others say, “Dear Lord!” or “God bless you” after someone sneezes even though they have never been inside a church or opened a Bible.

Lebrecht does not believe in particularism, the theological principle that only certain people are chosen by God for salvation. But he contends that the Jewish element is key to understanding these people and their roles in human history. For example, although Franz Kafka is often described as an absurdist storyteller about the torment of living under an oppressive state, scholar Gershom Scholem claims that almost every avant-gardism that neophytes see in Kafka’s work is grounded in the Kabbalah. Despite writing in German and being a product of the German education system, Kafka was certainly familiar with this tradition of Jewish mysticism. A gentile from Prague without that cultural background would not have written the same kind of stories as Kafka.

The work of writers whose Jewish culture was previously considered irrelevant or accidental is now being examined in a new light, a Judaizing light. This was not the case when the oft-republished Joseph Roth was alive. The plaque identifying his final residence in Paris calls him an “Austrian writer,” an adjective that would certainly not be used on any new plaques. Berta Ares Yáñez recently published a book on the influence of Eastern Hassidism on Joseph Roth’s work, and how it is better viewed in that religious-cultural tradition. In other words, Roth’s Jewishness defines him much more than his Austrian or German heritage. The same lens is being applied to other Jewish authors like Elias Canetti.

Perhaps this is not entirely unrelated to what historian Enzo Traverso called the “civil religion” of commemorating the Jewish victims of Nazism. Ever since the memory of the Holocaust became humanity’s moral horizon and Auschwitz became synonymous with hell on Earth (to paraphrase Holocaust survivor Elizabeth Roth), the entire intellectual contribution of the Jews has been reinterpreted to give the cultural and religious factors much more weight. For example, Hannah Arendt remains one of the most influential and widely read philosophers, but while her magnum opus, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), has been somewhat discredited, some of her lesser-known books about Judaism are sparking renewed interest – books like The Jew as Pariah (1978) and Rahel Varnhagen: The Life of a Jewish Woman (1957).

Enzo Traverso and other scholars argue that Jewish culture declined after 1950. “Israel has put an end to Modern Judaism,” writes Traverso in The End of Jewish Modernity (2016). “The Jewish diaspora was the critical conscience of the Western world. Israel survives as one of its devices of domination.” Lebrecht is not quite as definitive. “The birth of the state of Israel marks the beginning of a new chapter, not the end of the story.” Whatever it is, Israel indisputably represents a pause in the story that continues to politicize and divide scholars. Any analysis of the Jewish influence on the contemporary world is inevitably imbued with the emotions aroused by Israel’s existence, for better or for worse, but usually for worse.

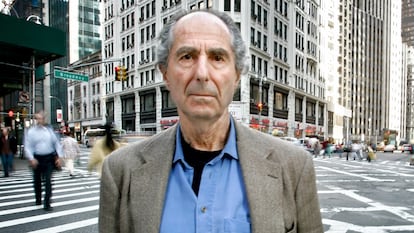

Jewishness may no longer be a transformative factor, but it is far from being irrelevant. It’s hard to imagine the culture of the latter half of the 20th century without the films of Woody Allen and Steven Spielberg, or the novels of Philip Roth. And it’s impossible to separate these men from their Jewish identities. Spielberg’s latest film, The Fabelmans, tells the intimate and semi-autobiographical story of a Jewish boy growing up in a post-WWII America still marked by antisemitism. Moreover, one of the most widely read and discussed writers in Europe today is Delphine Horvilleur, France’s first rabbi, a repentant Zionist and friend of Simone Veil, who was one of contemporary Europe’s most influential figures in her own right (and the recent subject of French biographical drama film, Simone: Woman of the Century).

The creation of the state of Israel has not stifled creativity nor has it extinguished critical analysis. Abundant evidence supports this, like the universal appeal of Amos Oz’s books, or an Israeli television industry with global influence, or ongoing Jewish contributions to the entertainment industry and popular culture. Studios in Tel Aviv feel like the golden age of Hollywood when Jewish movie magnates Samuel Goldwyn and the four Warner brothers ruled the industry. But if anyone wants to understand the impact of Israel on the 20th and early 21st centuries, just read Inside Story (2020) by Martin Amis, a fictionalized account of Amis’ relationship with three towering Jewish writers – Philip Larkin, Saul Bellow and Christopher Hitchens.

Contemplating the historical influence of Jewish people is a never-ending pursuit, and it continues to inspire new writing and academic debates that sometimes transcend university campuses. The Jews may no longer be changing the world, but they are still forcing it to think.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.