Enigmatic American author Thomas Pynchon returns to Gordita Beach

Los Angeles-area Huntington Library has acquired the reclusive writer’s literary archive

An American literary masterpiece was imagined in this tiny house in one of California’s many beach towns. It’s a white, one-bedroom duplex with a ground-level porch, just a few blocks from the Pacific Ocean in Manhattan Beach in southwestern Los Angeles County. This was Thomas Pynchon’s home in the late 1960s. For several weeks one summer, the most enigmatic author in American letters shut himself inside to write Gravity’s Rainbow (1973). Now, part of the native New Yorker has returned to California.

The Huntington Library, a private California research institution with an art museum and botanical gardens, recently announced that it acquired the 85-year-old writer’s literary archive for an undisclosed price. The Pynchon archive will be housed in the library established by 19th-century railroad magnate Henry Huntington in his San Marino mansion, about 12 miles (20 kilometers) northeast of downtown Los Angeles. The Huntington’s extensive collection includes eclectic items like one of 12 editions of the Gutenberg Bible printed on animal-skin parchment, and a lock of Abraham Lincoln’s hair snipped by his undertaker.

Placed end-to-end, the 48 boxes of Pynchon’s literary world measure almost 70 feet (21 meters) in length. The boxes contain drafts of his eight novels, correspondence, handwritten notes and abundant research material accumulated over the years by an author known for his long, dense novels. People who know Pynchon, who once worked for the Boeing Company, say he read specialized magazines like Scientific American to avoid his greatest nightmare – plagiarism.

Karla Nielsen, the Huntington Library’s curator of literary collections, considers it apropos that the reclusive writer’s papers ended up in this little corner of California. “His work is associated with many places, but half of his novels are set here,” said Nielsen, who was the first to contact Pynchon’s wife, Melanie Jackson, about buying the archive. A well-known literary agent in her own right, Jackson agreed, and a deal was struck after only a few years of negotiations.

Pynchon’s family issued a statement that they were “confident that the Pynchon archive had found its home” after learning of the scale of the Huntington’s resources about the aerospace industry and mathematics, two of the author’s favorite topics. The Huntington Library also has a vast collection of maps that includes some created by astronomer Charles Mason and surveyor Jeremiah Dixon, two British members of the Royal Society who surveyed and established the borders of Maryland, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia and West Virginia in the late 18th century. The two men became the protagonists of Pynchon’s novel, Mason and Dixon.

For Karla Nielsen, California played a pivotal role in the author’s work. “In the 20th century, it [California] symbolized US history – gold rushes, real estate booms, the arms industry and more,” said Nielsen. Prior to the acquisition, the Huntington Library did not have primary material from Pynchon, but it did have an extensive collection of academic research about the author.

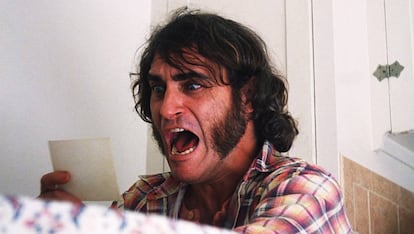

Pynchon’s 2009 novel, Inherent Vice, takes place in the fictional town of Gordita Beach, modeled after the real town of Manhattan Beach where the author lived in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In 2014, filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson adapted the novel for the big screen despite naysayers who said it couldn’t be done. Jim Hall, a Manhattan Beach resident who knew the author, told the Los Angeles Times in 1995 that Pynchon used to carry a small, plastic pig everywhere he went, and that the walls of his home were plastered with images of pigs.

It was rumored that besides consuming copious quantities of coffee and marijuana, Pynchon liked to be driven around Manhattan Beach aimlessly by teenage girls while he pontificated about the US defense industry. Some of these theories later made appearances in Gravity’s Rainbow (1973). Those aimless car rides sometimes had specific destinations, like going for chili burgers at Tommy’s, a fast-food burger chain.

One of the very few photographs from Pynchon’s life in Manhattan Beach purportedly shows the writer flashing the peace sign from behind a door. Purportedly because nothing but a hand and arm can be seen in the 1965 photo. Phyllis Gebauer, a friend of Pynchon’s who donated a number of his (allegedly) signed first editions to the University of California in 2011, is standing outside with a pig piñata, laughing.

The archive purchased by the Huntington Library does not include any photographs of the author, coveted items by his many fans. Pynchon has made a few appearances on The Simpsons animated series – with a paper bag over his head, of course. In 1974, to avoid being photographed, he sent a representative to accept the prestigious National Book Award on his behalf. Most of the publicly available photographs come from his Oyster Bay, Long Island high-school yearbook in 1953.

Pynchon’s literary archives won’t do much to dispel the mystery around his very private life, said Karla Nielsen. “The archive features material about his published work and doesn’t focus on his private life.” The documents were meticulously organized by the writer’s son, Jackson. “They are very well annotated and chronologically sequenced, but perhaps not in the way we would organize a collection that is going to be consulted by specialized academics,” said Nielsen.

Nielsen says the collection will be made available to anxiously awaiting academics by the end of 2024, and asks for patience while they organize all the material. It took the Huntington Library three years to process Octavia Butler’s archive. Butler is considered to be the first Black science fiction writer and was a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, the “genius” grant that Pynchon also won in 1988.

To the disappointment of many curious admirers of Pynchon’s work, the archive will only be made available to expert scholars. The library offers 200 fellowships for access to its reading room. Moreover, some documents will not be released, says Nielsen, but scholars will have access to a good portion of the archive. “I can’t think of a single archive that is completely unrestricted,” she said.

Pynchon’s letters

The only other major Pynchon collection is even more restricted. Since 1998, the Morgan Library in New York has held 216 letters written by the author between 1963 and 1983. The correspondence reveals Pynchon’s frequent relocations to Mexico City, San Francisco, Houston, Trinidad (California), London and New York. Researchers cannot view the letters while Pynchon is still alive.

Most of the Morgan Library letters are from Pynchon to his longtime editor, Candida Donadio. At least once a week, Pynchon wrote Donadio about progress on his latest work, copyright issues, writers he was reading and political events. The missives reveal clues about The Crying of Lot 49 and his research for Mason and Dixon. On several occasions, he pleaded for Donadio to respect his privacy.

Back in the 1960s, Pynchon told a poetry student who once visited his Manhattan Beach home that that one of his life goals was “to keep academics busy for several generations.” Perhaps the beginning of the end of the mystery lies inside 48 boxes in a historic mansion north of Gordita Beach.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.