Anne Frank: The investigation into the betrayal of the famous diarist remains open after nearly 80 years

A new book suggests a Dutch notary and member of the Jewish Council was the informant who revealed the hideout at Prinsengracht 263, but historians are skeptical

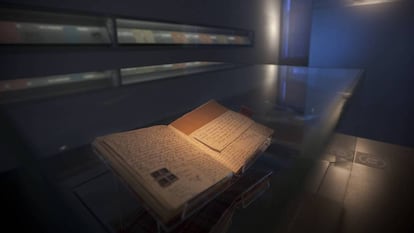

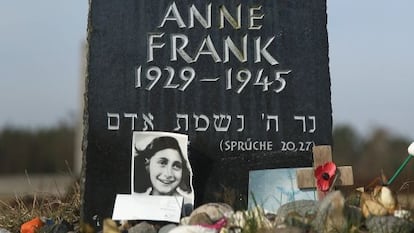

It has been nearly 78 years since the Nazis discovered the hideout being used by Anne Frank, her parents, her sister and four other people, on August 4, 1944. Hidden in an annex of a house on the canals of Amsterdam, after their capture they were sent to the concentration camps and only Anne’s father, Otto, survived. Anna and her sister, Margot, perished in Bergen-Belsen in 1945. Their mother, Edith, was killed at Auschwitz. According to historians, almost 28,000 Dutch Jews went into hiding like the Franks during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands in World War II. Around 12,000 of them were hunted down by the Nazis and suffered fates similar to those of Anne and her family and friends. The diary written by the young Anne during that time has become one of the best-known symbols of the Holocaust, and her name is synonymous with an unsolved case. No records of the search that led to their arrest remain and there are some 30 theories as to who might have tipped the occupiers off, if it was the work of collaborators or whether it was simply a raid related to the black market in ration cards.

A new book titled The Betrayal of Anne Frank, by Canadian author Rosemary Sullivan, details a six-year investigation carried out by an international team of researchers that suggests a Jewish notary named Arnold van den Bergh may have been the person who gave the Franks away. His name appears on an anonymous note received by Otto Frank after the war, and the researchers believe Van den Bergh may have acted to save his own family. Among the team members was Vince Pankoke, a former FBI agent. Van den Bergh was a member of the Jewish Council, an organization that kept lists of those in hiding and was forced to make them available to the Nazis before being sent to the camps themselves in 1943.

However, the conclusions of the investigation have been met with skepticism by Dutch historians, and the publishing house that printed the book in the Netherlands, Ambo Anthos, has since issued an apology, stating it should have taken a more “critical stance” and suggesting it will delay a second print run until concerns over the book are addressed.

In 1934, Otto and Edith Frank moved their family to the Netherlands from Frankfurt after Adolf Hitler gained power. Anne was four years old and Margot, seven. Once in Amsterdam, they installed themselves in a newly built neighborhood where many more Jewish families lived under the same circumstances. Otto found work at Opekta, a company that sold the fruit extract pectin for use in jam and which was headquartered at Prinsengracht 263. Almost a decade later, the rear annex of the building would become the hideout of the Frank family and Hermann and Auguste van Pels and their son Peter. Fritz Pfeffer, a dentist, completed the group of eight who took shelter from the terror of the Gestapo in the heart of the Dutch capital.

The German army invaded the Netherlands on May 10, 1940, and Otto immediately started making plans to move the family into the 50-square-meter annex, eventually doing so two years later. According to Johannes Houwink ten Cate, a specialist in the study of the Holocaust, Otto Frank “spread the word that they had left for Switzerland and went into hiding with his entire family in July 1942.”

“It was not an act typical of the time, as children were often separated from their parents because they had more chance of survival that way,” Ten Cate tells EL PAÍS. Jewish children were sent to places far away from their homes based on their appearance. As such, “a darker child would pass unnoticed in the south, whereas a blonder child would do so in the north, and Otto Frank was taking a risk by keeping everyone together. Although it is the case that he managed to hide them for two years,” says the historian.

On the morning of August 4, 1944, German police under the command of Austrian SS Sergeant Karl Silberbauer, raided Prinsengracht 263 and found the Franks and their companions. The Anne Frank House Museum says there are no official documents regarding the arrest, but Otto Frank and five people who helped the family during their hiding in 1945 identified the two Dutch agents who had been present from photographs. In her biography of Otto Frank, Carol Ann Lee suggests Tonny Ahlers, a member of the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands (NSB), informed the Gestapo of the whereabouts of the Franks and their companions. However, Ten Cate notes: “It has never been proven that Ahlers knew about the annex. The same thing happened with Lena Hartog, the wife of a worker at the company. Melissa Müller, Anne Frank’s biographer, suggested she was the guilty party but there is no proof of that either.”

Another suspect is Ans van Dijk, a Jewish woman who revealed several hideouts having helped to stow away people herself and who was executed as a collaborator in 1948. “That has also never been proven. The desire to know is one thing, but to really know the truth is quite different,” says Ten Cate, who believes the international investigation that forms the basis of Sullivan’s book did good work in analyzing and discarding numerous theories, including a telephone call from an informant received by Willy Lages, the chief of the SS security service in Amsterdam. But the historian maintains that they are mistaken to point the finger at Arnold van den Bergh.

The Betrayal of Anne Frank centers around the anonymous note received by Otto Frank after the war, which named Van den Bergh as the informant due to his place on the compromised Jewish Council. The Nazis drew up a register of all Dutch Jews and the researchers assume that Van den Bergh had access to the lists of those in hiding. “They maintain that he handed these over to protect his family,” says Ten Cate. “It is naïve to imagine that the Nazis would respect a Jew for passing them information during the biggest genocide in history. Even though Van den Bergh faked documents to pass himself off as half-Jewish to avoid deportation, when they found out he had to go into hiding with his family. It was February 1944 and Anne Frank was discovered in August of the same year. I don’t think it was the notary, who died in 1950, but his reputation is stained forever. The Jewish Council was heavily criticized after the war for the role it played as an instrument in the hands of the occupiers, but I have never heard anything about them having lists of hidden Jews.”

The problem, Ten Cate adds, is that publicity is already in overdrive. “Netflix is also behind this; but the reality is that life under the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands was so complex that it surpasses any fiction.”

Another name that has cropped up over the years is that of Willem van Maaren, a stockroom manager at Opekta. However, he was investigated after the war to no avail. It is also noteworthy that two people involved with those helping to hide the Franks were arrested for their activities on the black market.

In the view of historian Bart van der Boom, despite The Diary of Anne Frank first being published in 1947, it was the eponymous 1955 theatrical work and George Stevens’ 1959 movie that catapulted her to global fame. “For an American, the story of the Holocaust is the story of this young girl, but her story is no more valuable than other Jews in the same situation. Today she is almost a brand, and it tempting to present an eye-catching conclusion after a new search for possible informers,” says Van der Boom. “After the war, the Jewish Council got very bad press, and German war criminals said its members had been traitors in order to defend themselves. As such, the accusation against the notary and the Council itself is irresponsible without solid evidence. It is possible that there wasn’t a betrayal, but now we are being told that one Jew informed on another and that can be used as an anti-Semitic stereotype.”

The theory that someone could have seen strange comings and goings at the annex from the backyard and called the police can also not be ruled out. Historian David Barnouw tells EL PAÍS that eight people hiding in a house for two years could easily have been spotted by a neighbor. “Over the past few decades, more than 20 people have been accused of being the possible traitor. Because we need a traitor. The new investigation says its findings have a probability percentage of 85%. For a historian, this is ridiculous.”

Barnouw suspects there will always be new theories about the tragedy of Anne Frank and her family, and puts forward a reflection on their years in hiding: “If they had not been discovered, would they have survived the winter of hunger in 1944?” he asks, in reference to the famine provoked by the Nazi blockade on food transportation in the west of the country after the Allies had liberated the southern Netherlands. It is estimated that 22,000 people died as a result. “There are many things that we will probably never know about this case.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.