Eighty years later, book of children’s drawings prefaced by Aldous Huxley sees the light in Spain

The collection came out in 1938 to raise funds to help Spanish youngsters who were living through the Civil War

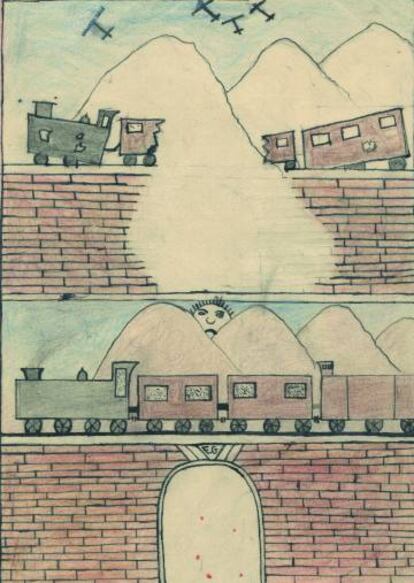

An airplane is a strange artifact. Especially for a child. And even more so if that child is going through a war. On the one hand, it looks like a toy zooming across the sky. On the other, it is a monster that hurls killer bombs out of its metal belly.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), planes were the thing that most impressed a lot of children. They were fascinating and menacing at the same time. This fascination was picked up on by the British novelist Aldous Huxley, who supported Republican Spain during the conflict.

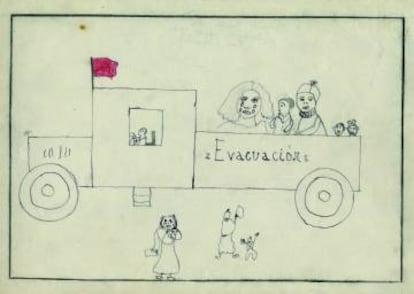

The author of Brave New World wrote the preface to a 1938 book, They Still Draw Pictures! A collection of 60 drawings made by Spanish children during the war, which is only now being published in Spain by La uña rota publishing house.

The book was originally released by The Spanish Child Welfare Association of America. Every copy sold for a dollar, and the proceeds went to the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker organization that did work “for the relief of children in Spain.” An accompanying exhibition opened at the Lord & Taylor department store in New York City, then traveled to museums in Boston and Worcester.

Commenting on the great number of airplanes found in these drawings, Huxley wrote that to the children of Spain, “the symbol of contemporary civilization, the one overwhelmingly significant fact in the world of today, is the military plane.”

Huxley was great friends with Juan Negrín, the Spanish prime minister between 1937 and 1939, and the writer gave him a copy of this book the year that it came out.

Spotlight on children

The wartime photographers Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, Henri Cartier-Bresson and the Spaniard José María Díaz Casariego featured youngsters in some of their work, as did several documentaries.

“In the Spanish conflict, the image of children as innocent victims was visually developed within a war context,” says Leticia Fernández-Fontecha, a poet and historian who is behind this modern edition of the book of children’s drawings.

“This is something that had not happened earlier, as there was no technology to allow it, nor had civilians been attacked on such a scale before,” she adds.

In many of the 60 original drawings that were collected for the book, the defenselessness of its authors becomes evident. In the children’s eyes, nothing is safe: nature, homes, families are under constant threat from the bombs and the fire.

The main goal was to show that children are the most vulnerable victims in a war context, but the project’s ultimate goal went further

Poet and historian Leticia Fernández-Fontecha

The material used for the book was not unlike the 1,872 items that were collected by a psychologist named Regina Lago, and which went on show in Paris. This was the first exercise in psychological therapy for children who had been through the war. Lago analyzed several effects of the psychological wounds caused by the conflict, “but she did not conduct a systematic study of the victims’ traumas,” notes Fernández-Fontecha. That came later, during the Second World War.

“Psychologists such as Anna Freud or Melanie Klein conducted in-depth analyses of the impact of war on English children, and they made an important distinction: on one hand, the fact of having been exposed to violence and bombs, and on the other, the trauma caused by separation anxiety. This was the origin of the first theories on the matter.”

And so the book of drawings with an introduction by Aldous Huxley was something of a pioneer on this matter. “The main goal was to show that children are the most vulnerable victims in a war context, but the project’s ultimate goal went further. It was not just about denouncing the situation endured by these minors. They meant to open up a space where the latter could directly retell their own experiences,” says Fernández-Fontecha.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.