Spain to prepare its first inventory of sites affected by radioactive contamination after years of delays and a EU warning

Despite the existence of at least six areas affected by nuclear accidents and other industrial activities, the country still does not have an official catalogue that includes locations and clean-up plans

Following an adverse ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union and several decades of delays, Spain has approved legislation to bring new transparency to a matter that has been shrouded in secrecy not only since the days of Franco’s dictatorship, but also during the subsequent 45 years of democracy: the state of land that was accidentally contaminated with radioactive material.

In Spain there are at least six sites affected by this problem. Although authorities are aware of them, these sites are not officially recognized as such, nor is there any oversight of ongoing control and clean-up measures, as established in a European directive of December 2013. Various Spanish governments, whether led by the conservative Popular Party (PP) or by the Socialist Party (PSOE), have failed to completely transpose that directive into national legislation despite repeated warnings from Brussels.

Last week, the Spanish government published a royal decree in the Official State Gazette (BOE) approving regulations that affect nuclear and radioactive facilities. The sixth additional provision establishes that the Ministry for the Ecological Transition “will prepare and maintain an updated inventory of radiologically contaminated soil or land, and of soil or lands with restrictions on use.” This inventory must include, among other things, the cause of the radiological contamination and its scope, the “decontamination action carried out and forecast,” and a description of the “control measures and restrictions on use.”

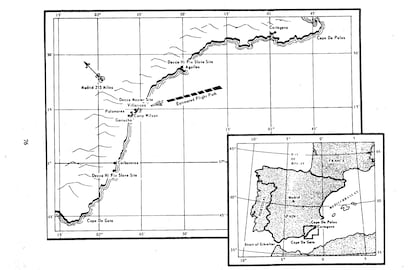

The best-known example is the Palomares incident, the worst nuclear accident of the Cold War. In January 1966, a B-52 bomber and a KC-135 tanker plane of the United States Air Force collided during a mid-air refuelling operation and dropped four thermonuclear (hydrogen) bombs near the village of Palomares in southeastern Spain, in Almería province. Two bombs were recovered intact, but two others dispersed their plutonium load and contaminated the area, without detonating. Almost six decades later, there are still 50,000 cubic metres of contaminated land in Palomares. Its clean-up is still pending an agreement with the United States that has never been reached, and which is even less likely to be secured with the return of Donald Trump to the White House.

The U.S. Army, in collaboration with the Franco dictatorship, carried out a clean-up of the area right after the accident and paid out some compensation. But a 2007 study by the Center for Energy, Environment and Technology Research (Ciemat) confirmed that 40 hectares were still contaminated with plutonium. Three years later, in 2010, the same agency drew up a draft decontamination plan that has never been carried out due to the lack of agreement between Spain and the U.S. on where the waste will go. The various Spanish administrations have kept this clean-up plan under wraps, considering it classified material. When the new inventory is approved, the chapter dedicated to Palomares will have to include the “decontamination forecasts and actions” for this area. It will also have to list the plans for at least five more areas that the Nuclear Safety Council (CSN) has acknowledged are contaminated by radiation.

This acknowledgment, made through a a press release, came after EL PAÍS revealed in 2018 the existence of eight zones at various points on the banks of the Jarama Royal Irrigation Canal, which runs between Madrid and Toledo, in which sludge containing remains contaminated with Cesium-137 and Strontium-90, two radioactive isotopes, had been buried. The ditches, which remain unmarked because there is no official recognition or list declaring them as contaminated, are the result of an accident that occurred in 1970. Several dozen liters of highly radioactive liquid were poured out more than five decades ago from an experimental nuclear reactor located at the Juan Vigón National Nuclear Energy Center, in the University City of Madrid. The liquid seeped through the sewers and ended up in the Manzanares River; from there it passed into the Jarama River and the royal irrigation canal. The Franco regime did not implement any containment plan and hushed up the accident. It then carried out a secret clean-up operation and the sludge with a lower radioactive load was dropped in these ditches, whose existence was never communicated to the local population.

In fact, the mayors of the area and the authorities of the region of Castilla-La Mancha only learned of the existence of these sites through EL PAÍS in 2018. The newly approved royal decree specifies that the ministry must inform the Nuclear Safety Council, as well as regional and local authorities in whose territory the contaminated land is located.

European adverse ruling and delays

The obligation to have “basic safety standards for protection against the dangers arising from exposure to ionising radiation” is established by European Directive 2013/59/Euratom, which was approved in 2013 after the Fukushima disaster. This regulation gave EU members until 2018 to transpose all its content into their national legislation. In the case of Spain, this should materialize in the inventory that has not yet been approved and in a royal decree on radiologically contaminated soils that the Ministry for the Ecological Transition is still processing.

The European Commission has sent several warnings to Spain in recent years, telling it to comply with these obligations. The delay has been such that the Court of Justice of the EU condemned Spain in September 2023 for this reason, although without imposing sanctions beyond the payment of legal fees. If non-compliance continues, Spain risks being fined.

The regulation on nuclear and radioactive facilities published last week in the BOE replaced a similar one dating from 2008. The older one had already urged the Nuclear Safety Council to draw up “an inventory of the land or hydrological resources that it is aware have been affected by radiological contamination.” But after years without doing so, it was decided that it was first necessary to modify a Franco-era law on nuclear energy that dates back to 1965 and is still in force, and which did not even contemplate a definition for radiologically contaminated land. This modification of the law was not made until mid-2022, which now opens the door to a future inventory when the royal decree on contaminated land, which is still pending, is approved.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.