Spanish Civil War: The woman who took a baby rattle to her execution

Archeologists found the toy lying next to the body of Catalina Muñoz, who was shot in 1936 and buried in Palencia, northern Spain

In August 2011, a team of archeologists found a baby rattle inside a grave dating back to the Spanish Civil War. The flower-shaped toy was found lying next to a body that had been covered with quicklime and buried without a coffin. The scientists were divided: could this object really be from 1936? “It seemed like a joke,” recalls Almudena García-Rubio, an anthropologist at the Aranzadi Science Society who was there that day.

The team’s mission was disturbing enough as it was: they were looking for 250 victims of the Franco regime’s repression under a children’s playground at La Carcavilla park, in the city of Palencia, in northern Spain. The municipal cemetery had once been located here.

The rattle was handed over to Fermín Leizaola, an ethnographer who cut off a section of the toy and brought it close to a flame. The fragment quickly caught fire, leaving behind “a characteristic smell of camphor.” This proved that it was made of celluloid, a plastic developed in 1870 and widely used in everyday objects until the 1970s. The toy could indeed date back to the Civil War.

“This is the most striking and moving object that ever came out of a Civil War grave,” says García-Rubio, noting that no other similar artifact has been found in the nearly 600 graves that have been opened in Spain so far.

The toy and the story behind it also helped a family learn new facts about events that had been buried away for decades. Records from Palencia’s old cemetery showed that the body was that of Catalina Muñoz Arranz, a 37-year-old woman from Cevico de la Torre, a village located 30 kilometers from the provincial capital. She had four children when she was killed. The youngest was nine months old, and he was probably the owner of the rattle.

That baby is now an 83-year-old man who lives in a humble home on the main street in Cevico de la Torre, which has a population of around 400. He does not say much, stares straight ahead, and his hands are thick from a lifetime of manual labor that began at age eight. “I was a shepherd boy and later I worked in the fields. I never went to school,” he says, speaking inside the kitchen of a house that he shares with his wife and his daughter Martina, 56.

“I don’t remember anything about my mother,” he adds. “I don’t even know what her face was like, because we don’t have any photographs of her. It’s sad.”

After his mother’s death, Martín was raised by an aunt who also lived in the village. His father, Tomás de la Torre, was in prison on charges of murdering a supporter of the fascist-inspired political party Falange during a village brawl on May 3, 1936. He was sentenced to 17 years, but his wife suffered a worse fate. She was arrested on August 24, a little over a month after Francisco Franco’s uprising. She was tried at a court-martial where the mayor and two neighbors testified that they had seen her going to demonstrations, washing the blood off her husband’s clothes, cheering for Russia and booing the Civil Guard. She reportedly said: “We’ll win yet, and we’re going to cut you into little pieces.”

Catalina did not know how to read or write, according to the records of the trial, which are kept at the military archives in Ferrol. Her file describes her as a woman standing 1.51 meters tall, with dark eyes and hair, nicknamed Pitilina. On September 5, 1936 she testified and signed a statement admitting that she had been to demonstrations, but denying all the other charges.

Despite the lack of evidence, the court found her guilty of military rebellion, and sentenced her to death. She was executed on September 22 “at 5.30pm [...] from injuries caused by gunfire to her skull and chest,” the records read. This description fits neatly with the bone analysis conducted in 2011 by the anthropologists who dug up the body. Next to the bones there were also buttons and the rubber soles of her shoes, size 36.

Just a few meters down the road from Martín’s house, a senior residence is home to the only relative who still remembers Catalina: her daughter Lucía, sister to Martín. Now 94 years old, her memory is somewhat fragile and her hands are as broad as her brother’s. Sitting inside the visitors’ room, she recalls the day their mother was arrested.

“She ran outside with the baby and fell down in the backyard of a house, and they went to get her. She was wearing a black apron to cover herself. It’s all she had when she left the house,” says Lucía, who does not remember seeing her mother with a baby rattle, but who believes it was probably tucked inside the apron pocket.

“She was very hot-tempered, I’m like her in that way. If somebody ever said something to her... get ready. And that’s why they killed her. For the last few weeks I’ve been crying, thinking about it.”

Lucía was 11 when her mother was executed. Her grandfather took her in, and she began working as a house servant for the village’s wealthier residents. But the family could not afford a burial in Cevico.

“Of the hundred or so women who were murdered during the early months of the war in that area, Catalina Muñoz is the only one who was tried and sentenced to death. The rest were taken out for a paseo,” says Pablo García-Colmenares, a chair of contemporary history at Valladolid University and president of the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory in Palencia (ARMH). The paseos, literally strolls, were a euphemism used during the war when people would be taken out of their homes for a walk that ended in summary executions outside of town.

When Martín’s father was released from prison, he went to work in the Basque city of Bilbao. After retirement, he returned to Cevico and spent the last eight years of his life there. The family never discussed what had happened, and Martín never asked about his mother to prevent painful memories from resurfacing.

Martín did not even know that his mother had been buried in Palencia, and only recently saw a photograph of the toy that she took to the grave. Since nobody showed up to claim the body when the new cemetery was built, her remains were transferred there along with other victims of repression, but in a separate box.

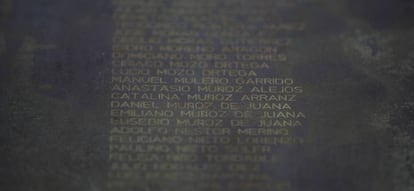

After learning about the rattle, Martín’s daughter Martina began the paperwork to recover Catalina’s body as well as the toy. Martina recently visited Palencia for the first time, and saw her grandmother’s name engraved on a monolith at La Carcavilla park that serves as a memorial to the victims of the Civil War. She now wants to keep the rattle inside an urn so that her own children and grandchildren will know the story.

“When I saw Catalina’s name engraved on the monolith, I had a strange empty feeling inside of me, but at the same time I am very happy to be able to get my grandmother back and take her next to my grandfather. I don’t think he is to blame for what happened to her, as people thought, he turned himself in to protect her, as an act of love,” says Martina. She says that her father has been reduced to tears by the story, and hopes that he will not die before Catalina’s body is returned to them.

Small treasures

Objects like the rattle are small treasures to contemporary archeologists, who apply scientific methods to the study of material recovered from the recent past. Sometimes, wedding rings and military insignia are clues that help identify the victims.

“Personal objects recovered near the bodies allow us to get close to the everyday lives of executed individuals,” writes García-Rubio in her book Mujeres en la Guerra Civil y la posguerra. Memoria y Educación (or, Women in the Civil War and postwar period. Memory and Education). “A pencil, a pair of glasses, a comb, a newspaper clipping with a story about the 1936 Tour de France... They are flashes of the lives of the victims, carried in their pockets at the time of their arrest.”

Alfredo González-Ruibal, an archeologist at the Scientific Research Council (CSIC) who has been digging at Civil War trenches and concentration camps for years, has recovered tens of thousands of objects that sum up the conflict in their own way. There are medals, crosses, perfume bottles, high-heeled shoes, and many kilograms of shrapnel and ammunition.

“The power of this type of archeology is not to retell an event that is already known, but to synthesize a moment in history through an image,” said González-Ruibal at a recent talk at the National Archeology Museum, where he said that Catalina’s baby rattle is one of the objects that best encapsulates the story of the Spanish Civil War.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.