The brothers who broke the Palomares nuclear cover-up in Spain

In 1966, a B-52 crashed over Almería, shedding three of its hydrogen bombs. The Franco regime launched a cover-up, but a wily US journalist and his beach-bum sibling uncovered the truth

Tito's is one of the most popular beach bars, or chiringuitos, in the Andalusian resort town of Mojácar, Almería, complete with palm trees, a terrace with sea views, oriental fusion cuisine, and live music every Sunday. But few of the vacationing customers here know anything about the owner, an outgoing, silver-haired American who has still not lost his accent half a century after following his brother here. "André lives in the Philippines these days. The only thing he's interested in is windsurfing," says Tito del Amo, aged 75.

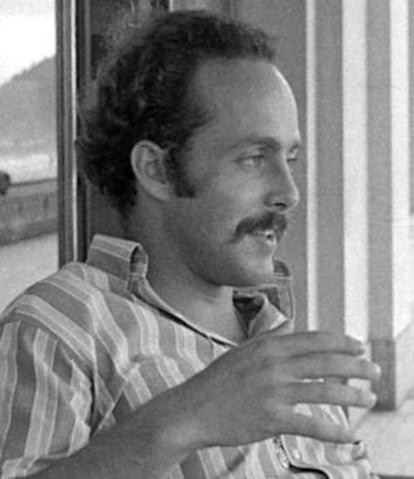

The Del Amo brothers were born in Los Angeles at the height of World War II. After finishing their studies, in the mid-1960s they decided to return to the land of their ancestors. André arrived first, in 1963, and found a job working for US news wire United Press International (UPI) in Madrid, under the directorship of veteran newsman Harry Stathos. Two years later, Tito arrived. "As soon as I got here, the first thing André told me was that I had to see two places: Mojácar and Pamplona. We tried the former, and I fell in love at first sight," he says.

And that was how the brothers became involved in the so-called Palomares nuclear incident. In the early hours of January 17, 1966, a B-52 belonging to the United States Strategic Air Command carrying four hydrogen bombs, each of them with a payload equivalent to 75 times the force that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, crashed into a KC-135 refueling plane over Almería. The entire crew of the KC-135 died in the accident, while four of the B-52's crew of seven survived. Three of its bombs fell to earth, two of them suffering a conventional explosion that scattered radioactive material over a wide area around the tiny community of Palomares. The fourth bomb sank to the bottom of the sea.

The US Embassy in Madrid immediately informed the government of General Francisco Franco, contacting the deputy prime minister and the foreign minister, as well as the US ambassador to Spain, Angie Duke. The international news agencies picked up on the story simultaneously, telling the world about the incident, but without mentioning the nuclear aspect. Deputy premier Ángel Muñoz-Grandes began "coordinating" with the US authorities on how to handle the media. The Spanish Air Force Ministry at first avoided referring to the B-52, instead mentioning "a long-distance jet," adding that a search was underway for what it called "elements of a secret military nature."

Franco had given instructions about what could and couldn't be said, vetoing any reference to nuclear weapons, as would later be confirmed by a recently declassified report by the US Department of State.

Franco's main concern was to protect Spain's tourism industry, the number-one source of revenue for the military regime. But Washington was also interested in keeping the potentially devastating accident under wraps. According the US State Department, Duke was told to do everything possible to persuade the Spanish authorities to continue to allow US military aircraft to fly over Spanish territory, although a ban was enforced for five days after the incident. The State Department's position was to tell the press absolutely nothing about what had happened, according to the recently declassified report.

For a while, the strategy worked. On February 19, two days after the accident, the media began to lose interest, and the government and the US authorities heaved a collective sigh of relief. Ángel Sagaz, the director general of North American affairs at Spain's Foreign Ministry, met with Duke to press upon her the impact of the Spanish public finding out that of the three bombs that fell on Almería, one was still at the bottom of the Mediterranean. Spain's fears of anything leaking about the incident were such that the government told the US authorities that it did not want it to release a statement thanking Spain for its cooperation. Silence was the preferred option. But what the diplomats did not know was that André del Amo was on his way to Almería with Leo White, correspondent for British red top the Daily Mirror. Colonel Barnett Young, the US Air Force's chief press officer warned them against sniffing around. "This is not the place for scandalous stories or crazy theories," he replied when asked if the B-52 might have been carrying nuclear weapons.

According to Tito del Amo, his brother pulled off the scoop as he was about to begin the return journey back to Madrid. "As he was leaving Almería, he came across a US military policeman who was looking for somebody to translate for him. He wanted local people to leave the area because of the radioactivity. André said nothing, and just translated. When he got to the car, he innocently asked if the authorities were worried about the bombs. The US military policeman told him everything."

The next day, The New York Times published UPI's story, as well as confirming that there were nuclear weapons aboard, one of which was still missing, and describing in detail the huge operation underway to find it in the area around Palomares. Declassified US documents show that when Franco read UPI's story he was so angry that he ordered the news to be suppressed in Spain, as well as banning the distribution of foreign newspapers and magazines, and ordering Sagaz to protest in the strongest possible terms to Duke, even threatening "unilateral measures." In the telegram sent to Washington after the meeting with the US ambassador, Sagaz spoke of his "extreme concern," "an emergency," and a "crisis." The US ambassador also called Stathos, demanding that he reveal his sources, which in the story he had said were from within the US Embassy in Madrid. Stathos apologized for not running the story past Duke, and said that he had obtained the information elsewhere.

The US government took 40 days to officially admit to the existence of the hydrogen bombs, despite mounting evidence. In doing so, it twisted the truth. Other declassified documents from the Atomic Energy Commission include references to efforts to align the different versions of events by the US authorities. These included a detailed questionnaire. The instructions were clear: refuse to answer any questions, distract attention and question the journalist's own sources. In answer to the question, "has the United States lost a hydrogen bomb?" the supposed answer was: "The US Defense Department has said that it is looking for classified material. For reasons of security, we cannot make further comments. We cannot deny or confirm that we are looking for a hydrogen bomb."

Should any journalists ask whether local people were at risk, the answer was: "I cannot talk in terms of numbers, because this is a classified matter. Do you know when something can be considered dangerous? What we can say is what we have already said: the experts have proved that this is not a danger to health."

Perhaps because of the mounting problems with Franco's censors and the US Embassy, and also because no progress was being made in finding the fourth bomb, Stathos and the correspondent for the Associated Press, the other US news agency in Spain, suggested to Tito del Amo that he follow the story. "They weren't making much progress, so they hired me to keep an eye on things here. I lived nearby. They paid me 500 pesetas a day, which was a fortune in those days. I hired a Seat 600 and spent six weeks in Palomares," he says.

Tito's job consisted of following the search for the bomb lying at the bottom of the sea, as well as the clean-up operation, sending any photographs and information he could find to Madrid. He took so many photographs that he had to travel to Murcia every two days to hand over the rolls of film to the engine driver of the Madrid train. "The whole thing was very difficult, because nobody wanted to say anything. For me it was just a job," remembers Tito, looking out over the Mediterranean just 18 kilometers from where the near-catastrophe took place.

Slow diplomacy

The fall to Earth of three bombs, and the subsequent radioactive contamination, are not just a stigma for the people living in and around Palomares. They continue to affect diplomatic relations between Spain and the United States. The two countries have been talking since 2005 (after prolonging the agreements of 1966 and 1997) on how to definitively clean up the area. Previous Spanish governments have carried out surveys that detected that there were still some 50,000 cubic meters of soil contaminated by plutonium (around half a kilogram in total), which was beginning to break down into americium.

Faced with the possible risk of radiation being unearthed due to construction work, the contaminated land was expropriated and fenced off (although it has been used to grow crops for decades). The United States paid almost $2 billion toward the cost of the operation.

But talks are progressing slowly. "It is still a major issue within our bilateral relations, but the Americans give the impression that they are dragging their feet," says a Spanish diplomatic source. The matter came up during the visit by US Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz to Madrid in November, and has always been on the agenda of any high-level meeting between officials from Madrid and Washington.

In February 2012, Spain's foreign minister, José Manuel García-Margallo, announced that the contaminated earth was going to be removed "very soon." In April of that year, the then-US secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, said good news was forthcoming, and that the matter would be settled before she left office. That did not happen: Obama won a second term, changed the ambassador to Madrid, and so the matter remains unresolved.

In the absence of any major progress, talks are focused on technical problems. CIEMAT, the Center for Energy, Environmental and Technological Research, has presented Spain's Nuclear Security Council with a plan to compact the contaminated soil, making it easier to treat. The United States does not consider this necessary, and says that taking away any residue would mean removing the soil wholesale. It has also asked for a report on whether the land contains any other residues from fertilizers or heavy metals.

Washington also wants guarantees that if the soil is removed, Spain would renounce all claims, something Madrid has already agreed to. The main obstacle is the precedent that removing the land would set: the United States has carried out nuclear testing in other areas of the planet, and could potentially face huge lawsuits requiring it to clean up contaminated land.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.