English, an unsolved issue in Catalan universities

The regional Parliament has postponed the requirement of a First Certificate level in the language in order to get a degree

The Catalan Parliament has postponed for four years the requirement introduced in 2014 that made it compulsory to have a Cambridge First Certificate – or equivalent – to get a degree. In the end, students who started a university program four years ago and are graduating this summer will not have to fulfill this requirement. The reason is that political parties have agreed that more public policies are needed to guarantee that students can reach this level. The decision comes after months of uncertainty because of the Catalan political situation due to the direct rule of the Spanish government in the wake of the regional Parliament’s unilateral bid for independence. In Catalonia and in the rest of Spain there is a significant percentage of undergraduates with insufficient language skills to hold a conversation in English.

Members of the regional Parliament, deans and students have been discussing during recent months the need to postpone having a compulsory English certificate to conclude university studies. This requirement was approved in 2014 by Andreu Mas-Colell, the former head of Economics and Knowledge in the Catalan government (Generalitat). This law required students have a B2 level of any foreign language – the vast majority of students choose English – and it was the responsibility of these students to obtain it.

The Interuniversitarian Council of Catalonia (CIC), an organization that coordinates the university system and advises the government of Catalonia in higher education matters, decided in June 2017 to establish a moratorium of four years for the requirement. For more than 10 months this recommendation remained in limbo and students graduating this year who do not have the English certificate did not know whether or not they could finish their studies.

After the CIC’s announcement, many Catalan university students felt relief. The main reason for postponing the requirement was that “there was still a high percentage of students with insufficient knowledge of languages”. Also, the English requirement raised some claims as it was a “premature measure” and “government did not provide enough resources”. “I think it is positive for it not to be mandatory now as students have more time to decide whether they want to take this qualification or not,” says Ariadna Gómez, student of Social Education at the University of Barcelona.

A person could be a magnificent veterinary surgeon but might not be fluent in English

The demand to amend the language application has been well received at most universities. In fact, some universities, such as the Autonomous University of Barcelona, were against the measure since the beginning of its application and therefore, decided that a bachelor’s degree would not be linked to the accreditation of the B2 level. “Half of our students have an insufficient level of English and we cannot establish a requirement that leaves our undergraduates without their degree,” explains the vice dean of International Relations of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB), Marius Martínez, adding that “a person can be a magnificent veterinary surgeon but he might not be fluent in English”.

Not all the universities in Catalonia have decided to remove the compulsory B2 level in their programs. Pompeu Fabra University, for instance, said it would be mandatory until last March 3 when the Catalan Parliament approved postponing the measure. "The request for a moratorium has not been reflected yet in any agreement of the Catalan government," argued Pablo Pareja and Cristina Gelpí, vice deans of the UPF some weeks ago. Besides, they said that the accreditation of another language would be "very positive" in academic aspects and in employment.

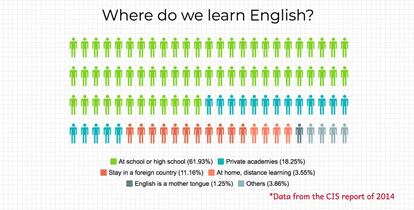

The main objective of the requirement, according to Mas-Colell, was to guarantee that students would not have problems with English or another language when they finish their degrees. The low level of English is an important issue in Spanish society. In 2014, according to the CIS (the Sociological Research Center), 61% of Spanish people said that they didn’t write or speak English although 94.8% consider it important to know a foreign language. Among those who say they know the language, only 19.4% have no difficulties holding an informal conversation. In relation with university students, Mercè Jou, the general secretary of CIC, says that “the organization did some level tests and the results indicated that a percentage of students didn’t have the correct level; so they decided to postpone the request for four years”.

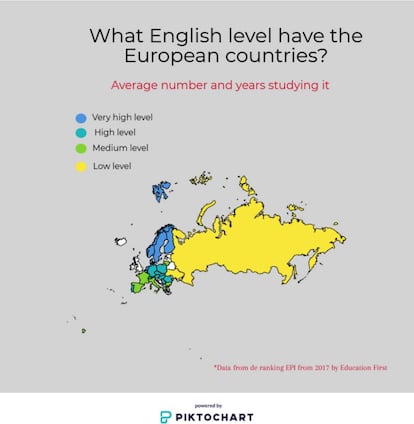

Mavi Salas, an English teacher at Premià de Mar (Barcelona) high school claims that the problem of English in Spain is more cultural than educational. For instance, the level of English in Spain and in Catalonia is not the same as in other European countries, such as Denmark, Sweden or Finland. According to a worldwide ranking that measures the level of English in 80 countries carried out by Educational First in 2017, a language school leader in teaching around the world, Spain has reached an average level of 28 worldwide, and 21 in Europe with respect to a total of 27 countries. Data like this show that there is a clear gap between learning English here and in other European countries. The study, which allows for a comparison between countries, indicates that while in Spain students spend an average of 9.80 years learning English, in Sweden (second country in the ranking) they study the language for 12.30 years.

In addition, contrary to the expectations regarding a report carried out by Eurostat in 2015, in Catalan schools children start learning English when they are three years, while in Sweden they start when they are between seven and 10 years old. But in Catalonia, teachers dedicate two or three hours per week to English, and in other countries English is one of the three basic subjects along with mathematics and Swedish. Also, in those countries, films and television programs are broadcast in their original version and with subtitles, meaning there is an important linguistic immersion. Related to this, Mavi explains: “I think the problem is more social than relative to the school. Nobody sees the real necessity of learning English: if TV series and films were in their original version we would gain a lot, we would have a half of the work done.”

A matter of money

Another reason why deans and students are against the B2 language requirement is that they consider it an elitist measure. Given that in secondary school the maximum level that can be acquired is a B1, some students are forced to take extracurricular lessons in private academies that can cost a minimum of €1,000 to €1,200 a year. This is an extra cost that not everybody can assume. “It is a snobbish measure because it goes against the people who perhaps have talent but not so much money,” claims Marius Martínez, vice rector of the UAB. Many young people support this argument, such as Bruna Naudó, a medicine student at the Barcelona University. “I think that the English level test is too expensive, so it’s good that they have decided not to maintain it as a requirement.”

Some of the university deans agree that the improvement of the English level is not the responsibility of universities and colleges, but it has to focus on elementary and secondary school, and mainly on baccalaureate level. “What we can’t do is to put the cart before the horse and ask for this requirement only in universities. The aim is good, but we must put resources and measures in all areas.”, says Anna Berga, general secretary of the private university University of Ramon Lull. Marius Martínez agrees with her and adds that the obligation of universities is to normalize the use of English as a language of “scientific work.”

An Elpais.cat project

Since November 2016, the Catalan edition of EL PAÍS, Elpais.cat, has been publishing a selection of news stories in English.

The texts are prepared by journalism students at the Pompeu Fabra University (UPF), who adapt content from EL PAÍS, adding extra information and explanation to these stories so that they can be understood in a global context.

This article was translated by Andrea Balart, Irina Balart and Maria Altarejos, and edited by the team at EL PAÍS English Edition.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.