The story of Madrid’s abandoned ‘beach’ for its working class

Built in 1932 in a style reminiscent of Le Corbusier and used by Robert Capa for a famous photograph, the landmark site is in a state of complete neglect after years of payment defaults

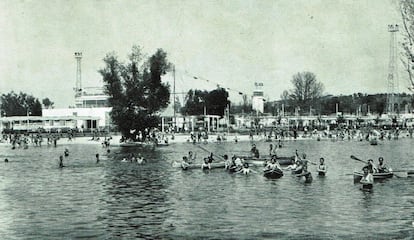

La Playa de Madrid was just 15 minutes from the Spanish capital’s Puerta del Sol square when it was inaugurated. Nine decades later, the distance is the same, but the premises developed by the architect Manuel Muñoz Monasterio in 1932 to create a “beach” in the landlocked city are in a state of complete disrepair.

The great leisure project for Madrid’s working class on the banks of the River Manzanares now houses fetid mattresses, crumpled beer cans, rank swimming pools, tattered tennis courts and facilities that are at risk of disappearing altogether.

Owned by the state agency Patrimonio Nacional, which manages Spain’s national heritage, La Playa de Madrid has been closed for six years. Defaults in rent payments forced it to close, and it subsequently became the target of vandalism. “There is no longer even any security,” says Juan García Vicente from the green group Ecologists in Action, who is upset by the state of dereliction of a site with social and architectural significance in the city’s history.

The access point to the “beach,” which borders La Zarzuela racetrack on one side and the Puerta de Hierro Sports Park (previously known as Parque Sindical) on the other, has not been opened since the authorities evicted staff and members at the end of October 2014. The company running the complex at that time, which belonged to the former president of the Spanish employers association CEOE, Arturo Fernández, received a court order to vacate the premises as it had failed to pay rent or any tax despite operating the five swimming pools, 11 tennis courts, four paddle courts, one roller-skating rink, four frontón courts, the cafeteria, the restaurant and the parking lot.

Arturo Fernández has left a hole in the National Heritage agency’s accounts to the tune of €867,006, which will have to be paid as soon as his company’s bankruptcy is resolved. The 3,000 Playa de Madrid members who had paid their fees were also denied access. Fernández’s contract had been renewed in 2011, despite the fact that he was already €466,831 in arrears. It was a sum that, according to the Court of Auditors, “he paid a few days before signing the new contract.”

To add insult to injury, EL PAÍS has learned that on July 30, National Heritage filed a complaint in court in a bid to evict the new company running the complex, Centro de Eventos Playa de Madrid, which is also behind on payments.

“It has not paid even one month’s rent and has run up a debt of €530,523,” says a National Heritage spokesperson. The new contract went into effect on October 17, 2017, after the president of National Heritage at the time, Alfredo Pérez de Armiñán, decided to lease the 184,800 square-meter property to a company that not only failed to pay rent, but also reneged on a commitment to invest €3.2 million to renovate the complex.

Meanwhile, under the National Heritage’s current president, Llanos Castellanos, an initiative is underway to revamp the more than 22,000 hectares of green spaces owned by the institution throughout the country, including the Playa de Madrid complex, which will be finalized when the judicial process ends. “The aim is to turn it into a sustainable property that is financially self-sufficient, and to make sure that what has happened does not happen again,” says Castellanos.

The phony beach was fashioned from a shallow river, from which “a beautiful arm of the sea” was created, to quote an ad from that period. But the dam that stored up the water to create a 300-meter shoreline was dismantled this January by the Tajo Water Confederation so that the river could follow its natural course unimpeded, according to García Vicente.

“It was a very interesting dam because it still allowed the water to flow and remain clean,” says Alberto Tellería, a member of the Madrid Citizenship and Heritage Association, who still remembers the complex’s dance floor and the announcement of a design competition for cheap evening dresses in 1934.

The “beach” was very popular among the working classes during the Second Republic, before Francisco Franco’s air forces razed it. And it was there that the photojournalist Robert Capa constructed his iconic image of of two militiamen greeting each other under the lighthouse tower.

But unpaid dues and ignored commitments have proved the ruin of the site, which is these days trapped between two highways. “These are public facilities of extraordinary significance,” says Juan García Vicente, who has been fighting for years for a path that will connect Madrid with El Pardo, on the left bank of the river.

This path should be ready in a couple of months and access to the “beach” will be reserved for pedestrians and cyclists. Meanwhile, the dignity of the complex is still to be restored, which according to Carlos Ripoll, a member of the Madrid Architects Association (COAM), has an “impeccable” language all of its own.

The simple and modern lines of the structures designed by the creator of the Las Ventas bullfighting ring and the Santiago Bernabeu soccer stadium are hidden behind pines, cork oak and poplars, and they are reminiscent of the international tone set by Swiss architect Le Corbusier. Muñoz Monasterio, who sided with the regime after the civil war (1936-1939), carried out the post-war reconstruction in 1948, refurbishing it according to Franco’s taste, with slate roofs and spires. But the subsequent inauguration of the nearby Parque Sindical (now known as the Puerta de Hierro Sports Park) and water contamination ended Madrid’s dream of having a beach.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.