The story of the Málaga virus: The code that haunted Google’s cybersecurity center director for 30 years

After asking for help on social media, Bernardo Quintero has managed to locate the creator of the software that, besides infecting the university’s computers in the 1990s, sparked his passion for cybersecurity

In the early 1990s, an unknown virus infected the computers at the Polytechnic School of the University of Málaga. It wasn’t malicious, but it was a nuisance because no one knew what to do about the cyber bug.

A professor named Adolfo Cid challenged one of his students to find the solution in exchange for a higher grade. A young Bernardo Quintero accepted, succeeded, and, in addition to improving his grade, discovered his calling. Shortly afterward, he founded Hispasec, the first cybersecurity company established in Spain. And later, VirusTotal, which was acquired by Google in 2012. Today, Quintero is the director of Google’s cybersecurity center in Málaga, a personal and professional milestone that always left him with a lingering question: who created that virus to which he owes so much?

In many of the interviews Quintero, 51, has given to the media about his professional career, this episode was usually a starting point, as was the Spectrum computer his parents gave him. It always left an air of mystery, because he had never been able to find the person who had devised that surprising malicious code that changed his life. Everything pointed to it having been created at the university, and in fact, major antivirus companies like McAfee and Panda dubbed it the Málaga Virus.

The virus was unusually sophisticated for its time. And it was only 2,610 bytes in size: when an infected floppy disk or executable file was inserted, the virus ran in the background in memory and, from there, invisibly spread to any other floppy disk or executable file. “It didn’t delete anything” or prevent the computer from being used, Quintero explains in a conversation with EL PAÍS. However, on the first day of every month it would launch a message: HB=ETA=ASSASSINS. DEATH PENALTY FOR TERRORISM — a reference to the now-defunct Basque terror group ETA. At that time, ETA attacks were almost weekly.

Last week, Quintero decided to have another shot at solving the mystery. He had already tried in 2022 without results, but wanted to try again: “If you have any leads or simply want to claim your youthful masterpiece, make yourself known!” he wrote last Monday in a social media post. “I was looking for nostalgia, talent, the chance to thank the author for the challenge it posed me,” says the IT expert. Those who know Quintero expected he would succeed sooner or later, but he wasn’t so sure. Even less so when the first responses arrived — vague messages pointing in different directions without supporting evidence. He studied five of them carefully because they included more details, but ultimately dismissed them.

Meanwhile, he returned to the original code in search of new clues he hadn’t noticed as a teenager. He found only one: two bytes — 4B and 49, which in ASCII code translate to KI — that were not part of any instruction and appeared as a signature. He then examined the second version of the virus, named Málaga II, which was an evolution of the first — it also sent the same message on the 15th of every month — and contained more unused bytes, which this time could be read as: KIKESOYYO (I am Kike in English).

To Quintero, named Doctor Honoris Causa by the University of Málaga this year, it no longer seemed a coincidence. It felt like the author was saying, “here I am,” yet the messages he kept receiving led nowhere. Until Adolfo Ariza, an employee of the Córdoba City Council, wrote to him privately on LinkedIn. He said he knew the person behind the Málaga virus, had been his classmate at the Polytechnic School of Málaga between 1989 and 1995, and had witnessed firsthand the creation of that code.

In the message, he wrote: “He never intended to do anything bad, other than display those messages about ETA and test himself as a programmer.” The detail about the terrorist group was unknown, except to Quintero, so everything fell into place. Ariza gave him a name: Antonio Astorga. He also mentioned that Astorga had passed away a few years ago due to cancer.

Who is KIKE?

Quintero Googled Astorga’s name and discovered that he had been a computer science teacher at the Miraya del Mar institute in Torre del Mar, just a few miles from where Quintero lives in Vélez-Málaga, the city where he was born. There, among many other projects, the teacher had developed a program called Evalúa, the precursor to the current iPasen that the Andalusian regional government uses to track student performance and attendance across the region.

Everything made sense — except for the newly discovered KIKESOYYO, which did not match the mysterious man’s name. Later, Quintero found the contact information for Astorga’s sister online, wrote to her to tell the story, and they spoke on Thursday at 8:30 p.m. When he asked, he learned that Antonio’s middle name was Enrique and that the family called him Kike. She said that the virus sounded familiar from some family conversation, but that it would be better to speak with Sergio Astorga, who, like his father, had studied computer science.

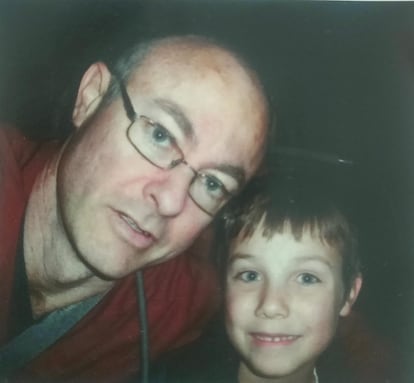

“I checked my phone around 11 p.m.,” recalls the 22-year-old, who lives in Rincón de la Victoria — just outside Málaga — and has just finished a degree in Software Engineering while taking his second year of Mathematics at the Spanish long-distance university UNED. He was amazed to see that it was Google’s director in Málaga writing to him. Even more so when Quintero arranged to meet him at 9:00 a.m. at the company’s facilities near the Port of Málaga.

There, last Friday, Quintero brought him up to speed on the story. “It meant a lot to me that he called to honor my father’s memory,” says the young man, who remembers that when he was 10, during one of his last conversations with his father, he was told that his greatest project had been a computer virus that took more than two years to develop.

“It’s been incredibly moving to close a 33-year circle,” Quintero explains, surprised that it had been someone so close geographically all along. “But it’s also bittersweet to learn of his passing, although meeting his son has been very special and emotional,” he adds, saying he expects to meet Sergio again in the future.

Quintero also left a message for KIKE on social media: “Wherever you are: I found your call, I found your signature, and it will not be in vain.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.