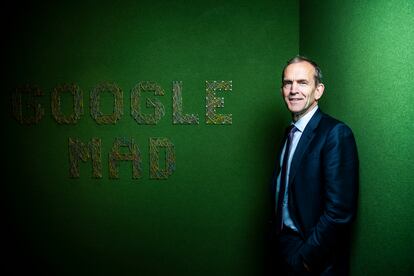

Google’s Kent Walker: ‘We are the geekiest and wackiest of the tech platforms’

The president of global affairs talks to EL PAÍS about cybersecurity, the company’s role in the war in Ukraine and whether it is a tool of US foreign policy

No one associates Google with a cybersecurity company. Kent Walker, president of global affairs at Google and Alphabet, is determined to change that perception. This week he has been on a European tour, where he has taken part in various events related to cybersecurity and highlighted the importance of protecting systems in the context of the cyberwar unleashed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

That’s the part of it that the 61-year-old from California can talk about. The other, more secretive side, involves meetings with high-level political leaders across Europe. Walker’s diplomatic tone matches his responsibilities. If Google were a country, he would be its foreign minister. The comparison is not unreasonable, given the company’s international influence and size: Alphabet’s market capitalization ($1.2 trillion) is practically equivalent to the gross domestic product (GDP) of a country like Spain ($1.4 trillion). Walker has more than 30 years of experience in the fields of technology, law and politics. He was Assistant United States Attorney in San Francisco and Washington D.C., where he started one of the first computer crime units in the country. He was later an adviser to the US Attorney General on tech policy issues. In 2006, he joined Google after working at Netscape, AOL and eBay. Walker spoke to EL PAÍS shortly before catching a plane to Prague, the last stage of his trip before returning to the US.

Question. What can Google offer in the field of cybersecurity?

Answer. We are one of the most attacked websites in the world, but we also keep more people safe than any other company in the world. And we’ve had opportunities to learn since we suffered a major cyberattack in 2009 [known as Operation Aurora]. At the time, we had a model that was a high perimeter model, high walls, but weaker defenses inside. We learned that when attackers once got in, they were able to exploit it. We shifted to a model called Zero Trust, where at every stage you have to certify your credentials, but you need to be able to do it easily. Otherwise, users won’t do it. We are pushing the concept of security by design. So instead of security products, we talk about secure products. Security is built in, not bolted on after the fact.

Q. You argue that companies and governments should be more transparent about the cyberattacks they suffer. But nobody likes to admit that their defenses have been compromised.

A. As a former federal prosecutor in the United States, I am familiar with this problem. When we suffered the cyberattack in 2009, we researched the attack, and we learned that there are 50 other companies that have been attacked as well as government agencies. And either they had not found the attacks or they had decided not to go public with the attacks. We decided it was important to change that. So we announced the attack, and we attributed it [to the Chinese government]. So we’re doing more and more on this. That’s an important part of accountability in the global security ecosystem.

Q. Ukraine is one of the global cybersecurity hotspots. What is Google’s role in the war?

A. In Ukraine, there is a military war and an economic war. But there’s also a cyberwar and an information war. And these wars are still continuing. On the cyberwar side, we saw attacks from threat actors coming. We worked with the Ukrainian government to shield their Gmail through our advance protection program, and we’ve identified and stopped hundreds of different attacks. We have something called Project Shield, which originally was for journalists and small publications that were experiencing denial of service attacks. We work with the Ukrainian government on things like air raid alerts. People in Ukraine who have Android phones would get a notice that missiles or bombs were coming in and could go to bomb shelters. We removed Russia Today, RT and Sputnik because they were pushing disinformation and false claims about the war. YouTube remains available throughout the region, including in Russia, as a channel that others can use to provide accurate information about what’s going on.

Q. Are you still operating in Russia?

A. We have stopped a substantial portion of our business in Russia. We no longer take ads in Russia. We no longer display ads in Russia. We have pulled our team out of Russia, so we no longer have employees in the country. The Russian government has fined us hundreds of millions of euros, and we’ve actually declared bankruptcy as a response to that.

Q. How do you choose which countries to operate in and which to not?

A. It’s a complex balance. We are constantly trying to honor our mission of providing access to information, organize the world’s information, make it universally accessible. But we also recognize the need to comply with local laws. And different countries around the world have different laws about what information is appropriate or not. There sometimes comes a time when we cannot do both of those things simultaneously. Famously, in 2010, we had to move our services outside of China and Google Consumer Services are no longer available in China because of the Great Firewall blocking access. We want to stay in as many countries as we can for as long as we can and provide as much information as we can. But sometimes that becomes too difficult.

Q. To what extent do you think Google is a tool of US foreign policy?

A. We think of ourselves as a company that is serving people throughout the world. We have offices in more than 40 different countries. It is important that we engage with open democratic societies of all description, and we support the notion of equal access to information no matter what country you’re coming from. So how do we engage in that and be a responsible global citizen while also recognizing that we have deep ties and relationship with lots of countries around the world, whether it’s the United States or many other countries in Europe or increasingly Latin America? I think of us as a platform, as a tool for people to be able to find information and accomplish things in their lives.

Q. The US and China are engaged in a silent battle for technological supremacy. Don’t they consider Google as a piece in this chess game?

A. We’re not allowed to provide consumer services in China. But we are trying to provide services in as many countries as we can around the world. We are in many ways the geekiest, the wackiest of the tech platforms. Roughly half of our employees are engineers. And what the engineers most want to do is solve problems for people around the world. The fact that more than half the world is now on the internet is, I think, a real achievement because it’s allowed people to have access to information. It’s a tool that makes people’s lives better across the world, without regard to which country you’re in.

Q. The European Union has recently approved two important regulations, the Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act, which directly affect your business. What do you think about them? Do you think Brussels has listened to you?

A. We believe it is good for democracies to regulate technology, establish clear guidelines and build trust. We are engaging both the legislative process to shed light on some of the issues that we’ve encountered in our experience, but also in regulatory dialogue. Once the laws have passed, how should they be interpreted? What do they mean? That’s true for the Digital Markets Act [DMA] and the Digital Services Act[DSA], just as it was before for GDPR [General Data Protection Regulation]. The Data Act, the Data Governance Act, the Privacy Act, the European Media Freedom Act, among others, are coming soon, and we are working constructively with governments to try and get them to a good place.

Q. What do you think of the DSA and the DMA?

A. The DMA is mostly around competition, the DSA mostly around content moderation. They introduce some complexities in our business and we are trying to balance lots of different factors as we comply and work with the regulators. I think the EU has not resolved some key dilemmas. Different governments will in different places draw the line between freedom of expression and social responsibility, between usefulness and privacy, between anonymity and the value of reputation. These are important discussions.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.