Cybersecurity expert Gil Shwed: ‘You can shut down water pipelines to a city from a computer’

The co-founder of Check Point talks to EL PAÍS about how everything in today’s world, from personal information to key infrastructure, is at risk from cyberattacks

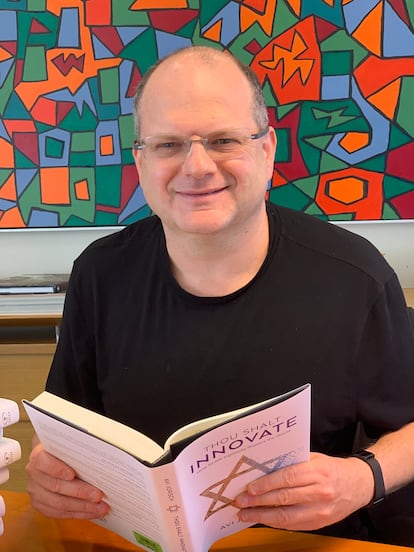

He began to program at the age of 13. By the time he was 15, he had started computer studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In 1993, when he was just 25, he and two colleagues founded Check Point, which is currently the most respected cybersecurity business in the world, with revenue exceeding $2.1 billion last year. Gil Shwed became an industry leader when he developed the first firewall, which is a type of program that protects a computer against external threats when it is online. His invention became a class of its own: all computers today have a firewall, irrespective of which company is the security provider.

When he appears at forums and events, the audience listens attentively to what he has to say. But perhaps what he doesn’t say is more interesting. It’s said that large multinationals and government ministries have sought his help to solve serious crises. But he declines to speak about this: in his line of business, confidentiality is the golden rule. Shwed spoke to EL PAÍS via video call from Jerusalem, his city of birth. The 54-year-old was wearing his characteristic black shirt and spoke from a very ordinary-looking desk. At first glance, it would be impossible to tell that he has an estimated fortune of around $3.4 billion, according to Forbes magazine.

The interview took place before Russia sent troops into Ukraine, but a few weeks after the cyberattack against Ukrainian government agencies that was attributed to pro-Russian groups. Both Shwed and his team declined to speak on this subject, which was considered “very sensitive.” Nor did they wish to make any comments following the invasion of Ukraine last week.

Question. Why should we be worried about cybersecurity?

Answer. I think today, especially after two years of Covid, when we are running our life through the cyberworld, it is more important than ever. Everything, our personal information, our critical infrastructure – electricity, water systems – are all now connected and controlled through the internet. That means that everything in our world is at risk. That can be personal, exploring where I’ve been, who did I meet, my health information all the way to shutting down the water pipelines to a certain city or shutting down the power or changing the way the trains move. In the cyberworld, the challenge is that everything is interconnected so the attacker might be somewhere else in the world, go to a city in Spain, Israel or France and cause the damage, and there’s very little chance that they will be caught and put to justice.

Q. Are we doing enough to tackle these challenges?

A. We all need to do more. We are providing tools that can protect against the fifth generation of cyberattacks. Most organizations today protect themselves against the third generation of attacks, that’s what we saw in the attack that took down a hospital [in Germany] for several weeks. The hospital had to move from digital systems to manual systems and that’s a huge impact on the hospital.

Q. What’s the fifth generation of cyberattacks?

A. Fifth-generation cyberattacks are what we call polymorphic. Every attack looks different. It may be the same attack, but it will not have a pattern you can identify. The second characteristic is that they are what we call multivector. Let’s say in the previous generation someone goes to your website and attacks it. In a fifth-generation cyberattack, the attack can start with an application or a game that you download to your phone. It downloads the malicious payload, which can steal the data and shut down the system. Fifth-generation attacks are difficult to detect and they are also very sophisticated in what they can do. We have seen malware that got into a water control system and changed the chemicals of the water. You can poison an entire nation by changing that kind of behavior.

Q. How can we defend ourselves against these attacks?

A. We need to protect against the latest attacks that were found yesterday, but our main challenge is to protect against the attacks we haven’t seen yet, the attacks of tomorrow. We have to protect against attacks that use 20-year-old technology because they can still hurt us. We need to protect against all vectors, the web, the mobile, the company cloud. In the cyberworld, people are not afraid because it’s very hard to catch them.

Q. To what extent has the pandemic led to an increase in cyberattacks?

A. It’s grown a lot. And it’s grown for two reasons. Firstly, the world became more connected and more dependent on the internet. During the pandemic, depending on the period, 70 to 90% of our life was on the net. Secondly, many things that two years ago were closed and protected are now wide open. Our crown jewels were just in the office, today they’re open to all employees who work from home. That means the attack surface has expanded. It also means that if someone attacks my home computer, they can gain access to my work systems. The world became softer, it’s much easier to penetrate.

Q. Some legal companies, such as Israel’s NSO Group, develop spy software. They exploit vulnerabilities to install themselves on systems, just like cybercriminals. Is it your job to fight these companies as well?

A. We are not in the same industry. When my researchers find a vulnerability we are not trying to take this vulnerability and make money off it or sell it to someone who could use it for good or bad reasons. It’s very clear to me that I want to be on the protection side. When we find some vulnerability in some code, we notify the owner, we disclose to them all the information and we educate them on how to fix it, and usually, we jointly publish it.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.