“Brexit wouldn’t have happened without Cambridge Analytica”

Whistleblower explains how he designed a cyber-war arsenal for the populist alt-right

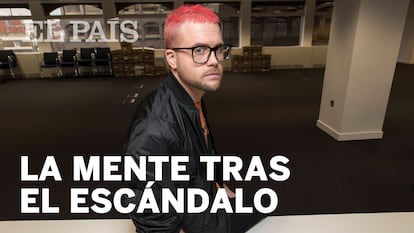

Christopher Wylie is the brains behind Cambridge Analytica (CA), the data analytics company that is being investigated for its role in the Donald Trump election campaign and the Brexit vote. The 28-year-old “gay Canadian vegan,” as he describes himself, put the most effective data mining machinery at the service of politics, but was shocked by how it was abused. Wylie has since exposed CA and Facebook for secretly mining the personal information of millions of Facebook accounts. After serving as a source for The Guardian and The New York Times, Wylie sat down with a small group of European journalists to talk about privacy, the failure of Facebook, and political interference.

Question: What was your motivation for speaking out?

Answer: My original goal was to expose the work of Cambridge Analytica, in part because I helped build it and I have a responsibility. If not to correct what has already been done, because there are things that can’t be undone, at least to inform authorities and the people.

Q: What is the most serious thing you have revealed?

People should be able to trust their democratic institutions. Cheating is cheating

A. First, the fact that there is a company that is a military contractor and also an advisor to the president of the United States. In modern democracies, the military is not allowed to take part in elections: why would we allow military contractors to, or for them to act as advisors for some of the most important politicians in the world? When a company with military clients creates an enormous civilian database, some of it collected illegally, there is a serious risk that the line between domestic surveillance and conventional market research will be blurred. People and lawmakers need to get up to date with technology and understand what these companies, Facebook and others which make money from personal data, really mean. It is important for people not to see it as something abstract but rather as something with a tangible impact.

Q. When did you realize it was time to stop?

A. It built up. The problem was I got lost in my own curiosity. It’s no excuse but I had million-dollar budgets, I could do any research I wanted. That was really attractive. I joined in June 2013 as research director of the SCL group [the parent company of CA] and I began to understand with the passing months what they were really doing. But you get used to the corporate culture. It’s not an excuse, but it was like that. You do more and more, each step isn’t much bigger than the last, until – bang, you have created a privatized NSA [National Security Agency].

Q. Then you left.

A. I left at the end of 2014. It was becoming more and more toxic, especially because Alexander Nix [Cambridge Analytica CEO] and Steve Bannon [former company vice president and ex-chief strategist to Donald Trump]. When Bannon arrived, this freedom to research which had attracted me at the beginning, turned into researching for what we now call the alt-right. Bannon came to London all the time, at least once a month, and we had a conference call with him every Monday morning.

Q. What was your role in Brexit? The latest revelations suggest a data company associated with CA played a key role in the result and helped bend the rules on electoral spending.

It’s different to knocking on a door and identifying yourself as part of a campaign

A. I didn’t work on the Brexit campaign but I was a phantom presence. I knew everything that happened.

Q. Do you believe Brexit wouldn’t have happened without CA?

A. Absolutely. It’s important because the referendum was won by less than 2% of the vote and a lot of money was spent on tailored ads based on personal data. This amount of money would buy you millions of impressions. If you targeted a small group, it could be the deciding factor. If you add up all the collectives that campaigned for Brexit, it was a third of everything that was spent.There has to be an investigation into the indications that they spent more than what was legally allowed. People should be able to trust their democratic institutions. Cheating is cheating. We are talking about the integrity of all democratic processes, it’s about the future of this country and of Europe more generally.

Q. Has CA worked in other European countries?

A. I know that there was a project in Italy when I was there, but I don’t have the details. I don’t know about others.

Q. Is data science dangerous for our society?

A. Data is our new electricity. Data is a tool. You can have a knife sitting on the table that can make a Michelin-star meal or be a weapon of murder. But it’s the same object. It’s the same thing with data. I don’t think data itself is a problem. There’s a lot of potential and amazing things we can do with data. But what CA has exposed is the failings, not just of our legislators but us as a society to think about what the boundaries are.

Q. Is it really that influential? How well can data help make predictions?

A. There’s no doubt that you can profile people and exploit this information. What people should think about is whether it’s appropriate for this to happen in a democratic process.

Q. There’s nothing new about political campaigns targeting undecided voting groups…

There’s no doubt that you can profile people and exploit this information

A. The difference is when you cheat, when you create a mediated reality for someone, when you target someone because you know they are more susceptible to believe conspiracy theories because you have profiled them, and you send them a spiral of fake news. It’s different to knocking on a door and identifying yourself as part of a campaign.

Q. What has been the failure of Facebook in all of this?

A. At the beginning, they said that there was no breach because the users had consented to give their data: in some part of the terms and conditions it says that your information could be used by applications, even if you don’t use them. One of the biggest failures of Facebook is to excessively legalize its terms and conditions and forget something so important as the reasonable expectation of the user.

Q. Your specialty was predicting fashion trends. How did you end up to your neck in politics?

A. It’s exactly the same. They are an expression of identity and of your role in society. You can think of Trump in terms of fashion. I see him like Crocs sandals. Before they were popular, they were ugly and then they became ugly again. But when they were popular everyone wore them. Donald Trump is the same as pair of Crocs sandals. It is an aesthetic that is objectively horrendous but people follow fashion. People adopt an aesthetic and later, when they see the photos, they will deeply regret it.

English version by Melissa Kitson.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.