Mexican gangs, the perfect fuel to double down on the federal offensive in Chicago

After several days of street clashes, the allegation that criminal groups are offering bounties to attack officers has increased pressure on the city

Clashes between residents and federal agents and police officers, tinged by the yellow smoke of tear gas, have become a recurrent scene in the month and a half since the deployment of federal forces to the streets of Chicago. And this is just beginning, according to statements by some of the highest-ranking officials in the Trump administration following government claims that Mexican gangs are offering rewards to attack federal officers.

Deployed as part of an immigration operation known as Midway Blitz in early September, their results have fallen short of expectations, with just over 1,000 undocumented immigrants detained so far, according to reports. As the weeks have passed, however, the mobilization’s objective has gradually shifted. A week ago, the National Guard was sent to respond to the “criminals” who had allegedly taken over the city and were torpedoing, ambushing, and assaulting officers. And this week, the accusation that Mexican criminal groups are offering bounties for attacks on federal agents or officials has increased the pressure on the city once again.

According to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Mexican criminal networks—which it does not specify by name—have directed their collaborators in the United States to monitor, harass, and even assassinate federal agents in the city. A reward system is also allegedly being introduced to incentivize violence against federal personnel: $2,000 for gathering information or disclosing personal data about agents, including photos and family details; between $5,000 and $10,000 for kidnapping or non-lethally assaulting ICE or Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents; and up to $50,000 for the murder of high-ranking officials.

The administration has promised to double down on its actions and increase the presence of federal agents in the cities that it accuses, again against all existing evidence, of being the most unsafe in the world. “We will not back down. President Trump and Secretary [of Homeland Security Kristi] Noem will give our forces the resources they need to succeed and clean up America’s streets,” said DHS DHS Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin on Tuesday.

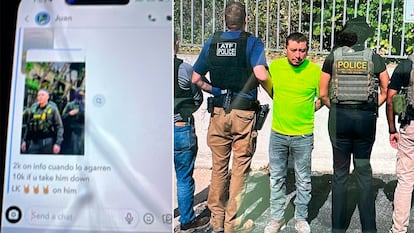

Although authorities have not provided evidence to support the intelligence claims on the rewards, reports of an arrest in early October appear to be the source. An alleged member of the Latin Kings gang, Mexican Juan Espinoza Martínez, whose entry into the country is unrecorded and who is presumed to be undocumented, was arrested in a Chicago suburb and charged on October 6 with offering a reward for the murder of Border Patrol Chief Gregory Bovino, who led the immigration raids that led to protests in Los Angeles in June and has maintained a high profile since. DHS cites evidence such as a Snapchat screenshot in which a user identified as “Juan” appears to offer $2,000 for information and $10,000 for the murder. A separate message referenced the Latin Kings.

Aside from this, there have been some other difficult-to-verify reports of the involvement of local criminal groups. On the first weekend of October, when Chicago became “a war zone,” according to the government, in the city’s marginalized, majority-Black south side, alleged gang members clashed with officers deployed to the area to defend their Latino neighbors. Reports and social media posts at the time claimed that shots had been fired, although no fatalities were reported, only several injuries and numerous arrests.

Using these types of violent confrontations, and many other peaceful ones against federal agents, the government maintains that its actions are necessary to maintain order in cities that, the White House claims, are out of control due to gang crime and the supposedly terrorist activities of far-left groups. In response, local authorities—in Chicago, but also in Portland, another city known for its progressive policies and targeted by Trump—critics and activists denounce that, on the contrary, it is federal action that is fanning the flames of conflict. “It is clear that this is not about security, this is not about deportations. This is the president of the United States of America seeking to foment chaos and fear in our streets,” said Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson, whom President Trump has called to be arrested.

Last week, federal judge April Perry accepted the arguments of Illinois authorities and imposed a 14-day freeze on the deployment of National Guard troops in the city. Perry, appointed to the position by former Democratic President Joe Biden, indicated in her preliminary decision that she saw no “credible evidence” that an insurrection was brewing in the streets, as the Trump administration claims. Instead, she noted that the troops could “add fuel to the fire.” Now, however, with reports of bounties offered for attacks on federal officers, the government’s position is strengthened.

The block ends at the end of next week, so it remains to be seen exactly what federal authorities’ next strategy will be, but for now, they received another setback in a local courtroom on Tuesday. The chief judge in Cook County, where Chicago is located, signed an order prohibiting ICE from arresting people in courthouses, a tactic deployed this year that has sparked protests both in Chicago and elsewhere across the country.

The order, which goes into effect Wednesday, prohibits the civil arrest of any “party, witness, or potential witness” while they are on their way to court proceedings. It includes arrests inside courthouses and in parking lots, surrounding sidewalks, and driveways.

The federal “takeover” of Democratic-run cities, and Chicago in particular, has been a threat and a promise of Trump’s since before he was elected. During the first days of his presidency, the city spent days on edge, expecting the arrival of federal forces. It took eight months, but they have arrived. And there are no signs that they are close to leaving; quite the contrary.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.