The curse of Bodie, California’s most famous ghost town

Visiting this remote spot in the Willow Creeks Valley is like stepping into a dream frozen in sepia. Everything is there. The houses, the objects, the half-burned stoves, the unopened letters. And the warning remains the same: don’t touch anything

At the end of the summer of 1859 — one that was surely hot, dusty, and full of guys in wide-brimmed hats sweating under their shirt collars — a small but determined group of gold prospectors decided to venture into Willow Creek Valley, a remote place in northern California whose only claim to fame was that, until then, there was absolutely nothing there except trees, rocks, silence, and the small but persistent possibility of finding something buried in the ground that could change your life.

One of them was William S. Bodey, a retired gunfighter who wasn’t looking for redemption so much as a retirement with a little more dignity than a card game on a rickety porch in Nevada. He was looking for gold, yes, but also a little peace. And he found it. He found both, in fact.

Bodey found gold and silver next to a nameless stream — because here even rivers have no identity until someone important names them or dies beside them — but three days later, the weather became a narrative device: a snowstorm — in October, in California, as if the weather had decided to reinterpret Fargo a hundred years ahead of time — fell on the valley and blanketed everything.

The rest of the expedition took refuge in a cave as best they could. Bodey, no. Bodey decided he was going to save the gold. Because, of course, that’s what he’d come for. But the bundles were heavy. And he was old. And the snow was deep. The result: the following day, his companions found his frozen corpse under a white mound and buried him on the spot, quickly and without ceremony. But not before taking all the gold. Because, well, he wasn’t going to need it anymore, was he?

This is where history becomes legend: what no one knew is that this act — this small piece of plunder, this “while we’re at it...” — was apparently the spiritual equivalent of opening Pandora’s box with a rusty crowbar. And the consequences weren’t going to come quickly, because curses, like the best slow-cooked dishes, are simmered over very, very low heat.

A year later, the gold vein was still yielding, so the prospectors founded a town. They named it after their old companion. But since no one knew exactly how to spell the deceased’s last name — because no one had bothered to ask or write it down, which is very much in the spirit of the American frontier — they recorded it as it sounded: Bodie. And so it stuck.

For a while, things were reasonably good. In 1890, a huge windfall appeared, and the place grew into a small town with over 10,000 officially registered residents (and probably an equal or greater number of people who preferred not to appear on any government lists for legal reasons). Bodie had it all: 65 saloons (six-five, that’s not a typo), 40 grocery and hardware stores, 10 banks, three funeral homes, two brass bands, and a jail. It was missing an Ikea and a TJ Maxx, but otherwise it was pretty self-sufficient.

And as often happens when gold, whiskey, guns, and testosterone are mixed without legal oversight or a civil code, things got a little out of hand. Fist fights and shootouts were routine. Bodie gained a reputation as a lawless land, and its inhabitants were dubbed (with some admiration and plenty of fear) “The Bad Men of Bodie.” And they probably were. Or at least they were training to become one.

Then, as if all this were part of a well-written narrative with a beginning, middle, climax, and final punishment, the downfall arrived.

By 1912, almost no one was left. Gold was scarce, saloons were closing one by one, the last local newspaper had gone from seven pages to two and a half, and people had started making off with everything they could fit in a cart. Or even things that didn’t fit, but whatever. The fact is that someone — no one knows who — started a fire in one of the older mines. And it razed the town. Almost completely. The only thing that miraculously remained intact was the church, a wooden structure but spared by the flames. Coincidence? Message? Poor town planning? Choose your own interpretation.

Local legends — which are the same as rumors, but with marketing hype — say that some of the last inhabitants took refuge in that church and saw, walking among the flames, the old gunman. Or his ghost. Or his ghostly image. And that they heard his voice: “Let this serve as a warning to you. DO NOT TOUCH WHAT IS MINE.” He said it in capital letters.

From then on, Bodie went into literal and figurative ghost mode. It emptied out. And a superstition took hold, which, like all useful superstitions, came with an instruction manual. Anyone who took anything from the town — a nail, a rock, a spoon containing the remains of 1910 soup — would find countless misfortunes heaped upon them: illness, death, divorce... So the last few to leave left everything exactly as it was. As if they expected to return the following day. As if they feared that a single movement, a single gesture of attachment, would doom them. And that’s why today, when you visit Bodie, it feels like someone hit the pause button in 1942, which was the year it was finally abandoned.

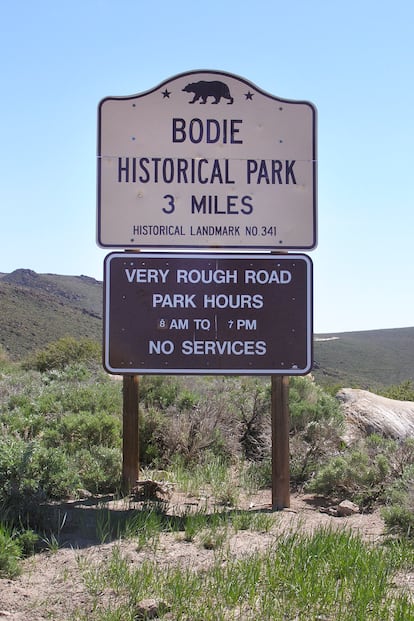

In 1961, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and in 1962, it became a state park (Bodie State Historic Park). And this is where the story takes a twist that M. Night Shyamalan couldn’t have dreamed of. It turns out the curse wasn’t exactly real; rather, it was completely fake. It was a fabrication created and promoted by the park rangers themselves.

Why? Because people in the 1960s and 1970s were the same as they are now, but in bell-bottoms: they’d come into Bodie, see a 100-year old china shop, and say things like, “Kevin, grab that, we’ll put it on the shelf in the living room.” They took jars, plates, grandfather clocks. A piano. Literally, someone took a piano. So the rangers, desperate, invented the curse story to see if, with luck, people would be a bit more cautious.

And it worked. For a while. Every week letters from repentant people and mysterious packages containing nails, plates, cutlery, and even rearview mirrors arrived at the park, along with handwritten notes saying: “Sorry, ever since I got this from Bodie, everything’s been going badly for me.” But the whole thing ended up turning into another curse: that of ironic tourism. Meta tourism. The kind that steals things only to later return them with the idea of, “Look how funny I am, I’ve been possessed by the spirit of William Bodey and now I regret it.”

So, tired of all this, a few years ago, the park’s managers decided to stop telling the story. They erased the legend and allowed the town to rust away in peace.

Today, visiting Bodie is like stepping into a dream frozen in sepia. Everything is there. The houses, the objects, the half-burned stoves, the unopened letters. And the warning remains the same: don’t touch anything. Don’t move anything. Don’t take anything. And not because of the curse, but because it’s not yours, Kevin.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.