Curtis Yarvin’s brave new world: ‘We need a corporate dictatorship to replace a dying democracy’

Recently, the provocateur has gone from being a marginal figure of the so-called ‘Dark Enlightenment’ to placing himself at the center of the American ideological war, cast as a kind of oracle to the MAGA universe

At first glance, Curtis Yarvin could be mistaken for the house philosopher of a West Coast cabal of billionaires, his orbit centered squarely in Silicon Valley. His professional career blends tech aspirations with literary affectation, such as naming two of his companies Urbit and Tlon, a direct reference to Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, the famous short story by Jorge Luis Borges.

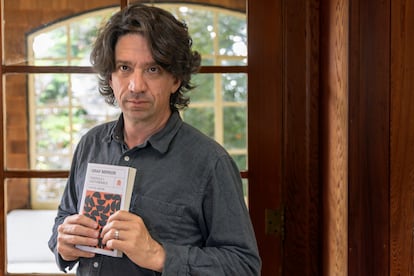

His recent book Gray Mirror. Fascicle 1: Disturbance reveals a different silhouette: an ambitious but scattered polymath, the kind of intellectual born of an age drowning in information and split by rage — a time when the public is angry, disoriented, and ready to swallow whatever nonsense comes packaged as truth.

There is, however, a third Yarvin: the youthful-looking provocateur with a restless mind who calls for scrapping democracy altogether, replacing it with a technocratic corporate tyranny.

In the past year, Yarvin has gone from being a marginal figure of the so-called “Dark Enlightenment” and courtier of Peter Thiel — one of the most influential personalities in Silicon Valley and the United States — to placing himself at the center of the American ideological war, cast as a kind of oracle to the MAGA universe, though he keeps a calculated distance. The New York Times, The Washington Post and The New Yorker have all profiled him; his ideas have bounced around a dozen television programs and popular podcasts on the radical right, including Tucker Carlson’s show.

Some insist he’s the philosopher behind Vice President J. D. Vance. His thinking, however, is less a finished system than a patchwork stitched from history, literature, and frequent deep dives into Wikipedia.

Yarvin opened the door of his home, in the exclusive Berkeley Hills neighborhood, half an hour from San Francisco, early on a Monday morning. He was in socks, wearing jeans and a shirt that looked like it had escaped from a bottle.

The premise of the conversation was a provocation: how to make sense of the turmoil the United States is going through? Over four hours in two interviews, his answers wound through oceanic digressions, alternating references to Orwell and García Márquez with venomous jabs at the elite and the political establishment. Extracting a coherent vision from these zigzags was no easy task. But Yarvin was always exceptionally receptive to questioning and criticism, as if what he most enjoyed was not being right, but the sheer sport of debating.

Question. You claim democracy is dying and liberal societies are decaying. What are the clearest signs of this?

Answer. First, let’s define “democracy.” Too often, it’s used in an Orwellian sense — as a euphemism for rule by selective institutions — when what we really mean is something closer to “civil society.” In practice, what most countries label as “democracy” is really a form of meritocratic oligarchy. This distinction is critical, because it shapes our analysis: what looks like democracy is usually institutional rule by a self-perpetuating elite.

If you look at American history, especially New England, you see how institutions like Harvard have been intertwined with power from the beginning. The educational and publishing industries, together with the civil service, compose what I call “the Cathedral.” The Cathedral is the brain, setting intellectual direction, while the deep state — the bureaucracy — is the machinery. Elite institutions like Harvard, Yale, and their peers set the boundaries for “legitimate science,” and thus, for government action.

This kind of regime — civil-society oligarchy — tends to decay in time. It becomes a “marketplace of ideas” where the point is process, not results. Harvard, for example, tries to run as such a marketplace. Science becomes another market for ideas, which is great — until it isn’t. Bad ideas can and do flourish; meritocracy produces its own failures.

Populism emerges as an unpredictable product of this idea marketplace. Ordinary people like “soccer moms on Facebook” start believing and propagating wild claims about vaccines or conspiracies. No one directs this. It’s not Russian propaganda. It just happens as the system’s natural output.

Q. Those moms are misled by disinformation. Now Robert F. Kennedy Jr., an anti-vaccine figure, runs the Department of Health. Doesn’t that reward magical thinking?

A. Absolutely. Magical thinking can now gain real power, which is dangerous and terrifying. We’re caught between exhausted institutional meritocracy on one side and increasingly erratic populism on the other. Both produce problems. The system can’t adapt; both sides are tired and trapped, like a bitterly feuding couple that knows each other’s flaws but can’t break the cycle.

The Covid pandemic, in my view, exposed these flaws with devastating clarity — much as Chernobyl did for the Soviet Union. Covid wasn’t a weapon; it was “normal science” spiraling into bureaucratic madness for grant funding, proof-of-problem, and institutional self-interest. The system incentivized risk, denial, and cover-ups; no single villain, just a process gone mad.

Q. You believe the virus did not come from the Wuhan market, but rather, it was a laboratory experiment gone wrong.

A. Exactly — and they covered it up, as shown by Katherine Eban’s excellent investigation in Vanity Fair. The “marketplace of ideas” is evolutionary — it produces winners. But evolution doesn’t always create beautiful flowers, just the most viral or empowering ideas. Meritocracies don’t always reward truth or competence. Sometimes they select for flashiness, reassurance, or profit. Back to vaccines: you’ve got “soccer moms” who don’t trust the system, and meanwhile, the elite system is capable of facilitating the creation of dangerous situations and then covering them up. Science journalism often failed its mission because it was too dependent on access to the very officials it was supposed to hold accountable.

Q. What’s the lesson? And what about Trump’s handling, since he wasn’t always the classic “populist” about Covid?

A. Authoritarian populism, despite its inherent dangers, can occasionally produce moments of raw common sense. Meanwhile, the intellectual elites will often conjure incredibly complex — and frankly, insane — ideas that they genuinely believe are intelligent, but which, in reality, are deeply flawed. In this specific sense, populism can, at times, serve as a kind of antidote. However, when taken to its extremes, like in Chile in the 1970s or Germany in the 1930s, it transforms into something entirely different and far more dangerous. Pure meritocracy has serious flaws. So too does authoritarian populism. The critical question then becomes: what happens when these two powerful, flawed forces collide?

Consider Trump and Covid. In early 2020, the mainstream narrative was that Covid was no big deal: go to Chinatown and lick the doorknobs. Then Trump, for reasons he only knows, flips. Suddenly, elite opinion (the “wife” in the metaphor) does a complete 180, out-hawking Trump. This exposes the inherent instability of the system: the elite doesn’t lead; it reacts to Trump, often becoming more radical in response, reminiscent of a character like Jack D. Ripper from Dr. Strangelove. In the end, Sweden alone kept its original, dovish line. I was a Covid hawk at first, but on balance, I think Sweden was right.

A broken system?

Q. For you, Trump didn’t break the system. He just revealed it was already broken?

A. Exactly. He exposed the system’s farcical, brittle condition, revealing the absurdity of it all, because it was already broken to begin with. That is the genuine nature of Trump. You cannot truly understand him by simply demonizing him, nor can you understand him by sanctifying him. You can only grasp his essence if you comprehend how this entire comedy functions. The 20th-century liberal elite, in my view, made the mistakes that Covid laid bare and then tried to hide them.

Returning to the marriage metaphor: Trump (the “husband”) acts chaotically and often self- destructively, while the elite system (the “wife”) responds with its own, sometimes worse, kind of madness. My conclusion is that the meritocratic elite system can’t be fixed; it endlessly cycles through the same pathologies. What about authoritarian populism? It’s a dangerous drug, but maybe — like venom from the Gila monster used to make Ozempic — it can be made useful. Can society harness populism, neutralize its poison, and turn it into a cure rather than a new affliction, without causing unintended damage?

Q. So, that’s your proposal?

A. Exactly. I’m not asking you to agree, only to consider whether it makes sense. The real work is finding a way to transform populism’s raw, chaotic energy into something that can renew a system that meritocracy can no longer maintain. That is the fundamental question that demands our attention.

Q. Do you see Trump as a hybrid of meritocracy and populism? Can he embody the CEO-authoritarian model you advocate for?

A. No. Just look at his record: he’s not a disciplined executive or an operational leader. The Trump Organization is all branding, not organization or real management. Compare that to someone like Elon Musk. Musk builds enormous, complex companies — but only succeeds when he has total control and works with genuinely competent partners, like Gwynne Shotwell at SpaceX. He’s a visionary, but not a manager; Trump lacks even the vision part. Someone like J. D. Vance is more interesting: he can speak both the language of the elite and the language of the people — a necessary kind of hybrid. Ultimately, government isn’t about divvying up power, but about results: who governs best?

Q. How does your CEO-dictator model fix this?

A. Aristocrats will exist, but not all need to compete for political control. Direct their ambition toward excellence — art, architecture, meaningful work. Those who enter government must do so in a structure that works, where ambition strengthens the system instead of undermining it. That’s the genius of enlightened monarchies: the best minds in arts and sciences gathered at the center, building a stronger state. When ambition lacks structure, talent fragments and the system is destabilized.

Q. So, how do you prevent chaos?

A. By having clear hierarchy, but still rewarding merit. Government should operate like a well-run company: a defined chain of command, logical progression, a shared mission. Ambitious people need legitimate ways to contribute, rather than feeling compelled to wreck the order just to be heard. Otherwise, you get civil wars, pointless revolutions, or paralyzing dysfunction. Just look at Latin America in the 20th century. Or at the U.S. immigration system — a convoluted, absurd mess that doesn’t work for anyone. That’s what happens when you lack a coherent structure for channeling energy and ambition.

Q. Political parties now focus on polarization over consensus, and migration drives that polarization.

A. True. Many migrants get used as political weapons without realizing it. They come as individuals seeking opportunity, but their very presence drags them into America’s larger political wars. Take California: it flipped from strongly Republican to reliably Democratic in just a few decades, because of immigration. Major shifts in political power never happen by accident.

Q. Isn’t MAGA’s aim to reduce diversity to restore white control?

A. I’m saying that high Hispanic immigration directly competes with African Americans for low-skilled jobs. That creates real economic tension in communities. And let’s be clear: many politicians who pushed mass migration did so to secure votes, not for moral reasons.

Q. Do you support current immigration policies?

A. No. The system is fundamentally senseless. The asylum process is a joke: fake stories, impossible bureaucracy, arbitrary outcomes. It’s Kafkaesque madness.

The red and blue empire

Q. I agree that the U.S. can’t take all the world’s refugees. But, in practice, it accepts only about 20%. That ratio has been quite stable for the last three decades.

A. Globally, people flee bad governments. Frequently, U.S. foreign policy has played a direct role in creating or sustaining those regimes. My idea is not far from Chomsky’s: many countries function better once the U.S. stops interfering in their affairs.

Q. That wasn’t the case in Venezuela.

A. True. But much regional disorder can be traced to attempts from the North to force a certain liberal utopia. This goes back generations, from John Reed to today.

Q. Like in Guatemala in the 1950s, where democracy was sabotaged.

A. I know the story. But look at Chile: Allende was democratically elected. He had connections with Harvard and the U.S. liberal establishment. Pinochet? Not really. The U.S. runs two empires: the Red Empire, the conservative one, consisting of the military and business interests like Exxon. And the Blue Empire, the liberal one: Harvard, the Monroe Doctrine, Latin American Studies. We don’t call the Blue an empire, but it functions as one.

Q. Returning to migration, the government knows who has Temporary Protected Status and who has humanitarian parole. That’s why they’re targeted.

A. Right. That highlights another mistake from the Trump years: they try to work within the existing system, pulling at its loose ends instead of simply cutting through. If you can’t fire the central actors, you end up targeting the easiest, most visible targets — like firing the interns because you can’t fire the bosses.

Q. The nuclear arsenal approach.

A. Yes, but without asking the vital questions: How do we cut the Gordian knot? And what do we replace it with? The first step is to ask: what kind of country do we want to build? We won’t fix a nightmare with stricter, incoherent rules. Look at educated migrants — if they’re not practicing law here, there’s little harm, but the law doesn’t account for that nuance.

Q. But there are laws and rules in the U.S. If migrants follow them, they should be allowed to stay.

A. Sure — mostly nonsense. They’re inherently incoherent, contradictory. Hard to respect. The system is ridiculous. We already agreed on that.

Q. I mean society as a whole works, despite dysfunctional and functional zones.

A. Yes, some things function, others don’t; generally, the closer to elite universities, the better things run. But overall, society is misaligned. Tens or hundreds of millions don’t do work that fits them or makes use of their abilities. America needs a fundamental reconstruction.

Q. Like Project 2025?

A. No, much more ambitious. Why do I argue for a CEO-style dictator? Because roughly every 75–80 years, America gets a president with that energy. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was the last. It’s a cyclical pattern, like a comet or earthquake.

Q. A democratic dictator.

A. Yes. FDR was like a character from Gabriel García Márquez. He emerged at a singular moment, the Great Depression, and fundamentally reshaped the country. But the “deep state” and “the Cathedral” are the world he built, the structures still defining the present. He didn’t do it alone. His revolution was led by the elites. That’s why we see him so differently from other figures like Hitler, who was also democratically elected, but in a more populist vein.

Q. CEO-style presidents failed in Latin America: Argentina, Chile, Peru, Mexico all tried.

A. They failed because they were used to running corporations, not societies. The scale and complexity are completely different; their powers were simply too small for the challenge. FDR, or historic leaders like Porfirio Díaz in Mexico or Juan Vicente Gómez in Venezuela, came closer to wielding true state power.

Q. But that does away with democracy.

A. Yes. Democracy, as we know it, is dying. Its authority once rested on the mass’s physical strength, on the threat of revolt from the masses. Now, “the people’s” power is symbolic.

Q. What do you propose in order to interpret history without falling into narratives imposed from above, such as those of the elite and the rationalism of Silicon Valley, which you criticize so much?

A. Good question. Right now, for “enemies of the system,” there’s no room for so-called “noble lies.” There’s no upside to deception. The most effective option is just telling the truth. Plato argued that ruling sometimes requires noble lies for social order; but today’s elite narrators are forced to keep up fictions to maintain control. A good example is the collective pretense that the European Union isn’t essentially a set of American satellite states. Everyone acts as though it’s not true, but everyone knows. The point is to block alternative stories. When real alternative narratives do appear, one factual error can ruin them — because they always come from a place of opposition with little margin for error.

Q. Your “corporate monarchy” vision resembles failed right-wing utopias. Why would it work differently in America?

A. My “corporate monarchy” idea could succeed in the U.S. precisely because America is the cultural and intellectual center of the world. When other countries try to govern like corporations, it devolves into “authoritarian populism” and alienates their own creative classes, who look to London or New York for inspiration, not Madrid or El Salvador. In the U.S., intellectuals see themselves at the center. This makes it possible — if not easy — to unite mind, prestige, science, and the arts around power, instead of relying only on force as so many peripheral regimes do. That unity is the only path to lasting, creative, and stable order without having to rely solely on brute force. It’s exceedingly difficult for places that are no longer recognized as centers of global power to sustain that necessary intellectual and cultural energy.

Q. Now that you mentioned El Salvador, you like Bukele a lot.

A. Yeah, I do. He’s doing the responsible thing by actively reaching out to American intellectuals, or at least American weirdos. That’s unusual, and honestly, pretty smart.

Q. But Bukele persecutes journalists, intellectuals, human rights defenders. Bottom line is: authoritarian regimes like Bukele’s are real and they always seem scared of the truth. How do you see truth, lies, and the roles of journalists and scientists, who are under attack?

A. They fear lies, too. Lies can destabilize as much as truth. But, in the end, truth has more power. I keep hearing that journalism and science are “under attack,” and they are. But let’s be honest: they’d be a lot easier to defend if they were faultless. No institution is, obviously, but the Times, for example, going years without an ombudsman… that’s a red flag about internal accountability.

Q. I worked at The New York Times for nearly six years. I know its dynamics. People there are in an honest pursuit of the truth. Sure, mistakes happen, but they avoid them like the plague.

A. It’s way less centralized than people imagine. It’s a big, powerful place, with both high ideals and big blind spots. Real criticism should see the ambition and the flaws.

Corporate monarchy

Q. Going back to your “corporate monarchy” vision, it resembles past right-wing utopias that often descended into chaos and repression. What makes your vision different, and why wouldn’t it have the same outcome?

A. We use “authoritarianism” to re-fight 20th-century battles. People act them out, often without realizing. My point is you get bureaucracy, or you get top-down clarity, like the military or a well-run restaurant, which work in stark contrast to the way most current governments function. It comes down to hierarchy and mission. Systems work best when incentives are clear.

Q. But how do you prevent your model from becoming a techno-authoritarian nightmare? Even in the United States, we are seeing a worrisome trend toward authoritarianism. And that’s not an opinion.

A. A company’s inherent mission is to cultivate and increase the value of its assets. You build a government to raise the “stock price” — a metaphor for social prosperity — of society and foster human flourishing. The goal should be to improve human flourishing, not to maximize GDP, in tune with the old Roman saying: salus populi suprema lex, the welfare of the people is the highest law. Incentives must align for everyone, from CEO to citizen, so good outcomes emerge by design. And I don’t think that I would find anyone who would disagree that human flourishing is the goal of governance, unless it was an insane libertarian.

Q. Your country is a garden, with the managers tending it. That sounds like Harvard’s “human capital” model, which you criticize all the time.

A. Harvard’s approach grew alongside America’s rise — it’s not all bad. But the same concept fits Roosevelt and, with a twist, someone like Franco. The trick is avoiding the downsides of both “Cathedral” bureaucracy and heavy-handed repression.

Q. And where do civil liberties fit? How do you guarantee them?

A. A well-designed system has no reason to persecute people. It’s like: no restaurant wants to poison customers. When incentives are right, you don’t depend on saints, you depend on self-interest working for the common good.

Q. Aren’t figures like Elon Musk or Chomsky only possible where rights and liberties are guaranteed?

A. Depends on how secure the regime is. Harvard once tolerated dissent. Think of Chomsky. Less likely now. Secure regimes let critics talk; weak regimes clamp down.

Q. Trump threatening mainstream media, cutting subsidies for companies and grants for science and universities is just the system showing its flaws?

A. Exactly. Every system has bad apples and errors, whether it’s monarchy, corporations, or The New York Times. None should be sacred or immune from criticism.

Q. Would dissent survive in your company-dictatorship country?

A. It depends on how secure the leadership feels. Elizabethan England allowed wild creativity, but the monarchy was insecure physically and militarily. The country was flourishing, yet the monarchy could sometimes act as a police state. There were lines you didn’t cross, even in literature. Ben Johnson’s play The Isle of Dogs was banned and is now lost. That episode serves as a compelling illustration of this tension. The more confident the state, the more open it is. What’s more: places like Dubai prove that you can live freely under a dictatorship, at least in some respects. You’re not free to challenge the system, sure, but you are free to live your life without fear, as long as you don’t try to change the regime.

MAGA 2.0

Q. How does your proposal differ from the MAGA vision, a reactionary, nostalgic attempt to restore an illusion of greatness? Isn’t your “corporate monarchy” just MAGA 2.0 with a Silicon Valley skin?

A. That’s a fair question. But both the establishment and MAGA are disconnected from reality. MAGA is all “common sense” but no practical plan. Tariffs? I’m actually for mercantilism, but you need real technocrats — like in East Asia — not just applause lines. It’s as complex as putting a rocket in space.

Q. Do we need that kind of technocratic focus? And is anyone working on it?

A. We need it badly, but no, nobody’s doing it. The main myth nowadays is libertarian: “Set the right rules, step aside, and let the market fix everything.” Total fantasy. Their reading of history is inaccurate. For example, Lincoln was a leftist, hugely admired by Marx, yet today’s MAGA people call him conservative.

Q. Are they feeding people with disinformation?

A. Pretty much. That sabotages real dissent, which needs a truthful foundation.

Q. Your ideological circle has embraced fearmongering. Isn’t this a politics of fear — casting the other as a threat to society — just emotional manipulation by elites?

A. Fear sells.

Q. Would you say that same kind of fear and hype is applicable to migrants?

A. Absolutely. Whenever I see fear around “the other,” my first question is: is it real? It’s just as useless to be afraid of something imaginary as it is to stick your head in the sand about a real threat. With migration, I see two big myths. One, from the old missionary mindset: you know, the belief that everyone, deep down, wants to become a Western European. They tried that in the colonies, then called it the Third World. When that approach failed, it turned into: “Let’s bring them here and civilize them in Europe”.

Q. That’s a pretty particular take, don’t you think?

A. Sure, but look at Merkel’s “wir schaffen das,” we can do this, moment. The real message was: “We have the tech, the structure, the will to turn migrants into Westerners.” Okay, the Syrian crisis was real, but let’s not kid ourselves: migrants always shift the political balance of a country because they are political allies of the force opening the door for them. They’re not an invading army, but just by being there, they change the game.

Q. Really?

A. Not now, but in 50 years.

Q. It’s not because of the unequal distribution of wealth and opportunities?

A. If 500 million sub-Saharan Africans came to North America, which is possible, the country would be very different. People often ignore the issue of scale when they talk about mass migration. If it cost $300 to get here, many would find a way, even selling a cow, and that would change everything. My father was a diplomat in Nigeria, and I once told him it was wrong to keep people out of the U.S. based on where they were born or the GPS coordinates. He told me, “Curtis, if you get rid of borders, you have no idea what this country would look like.”

The missionary Left says helping the world’s poor is noble. But today’s Left is more cynical, using benefits to buy votes, not investing in people’s long-term good. Just look at what’s happened to Black America since 1960. So many communities have been left behind and are in ruins while politicians pretend to care.

Q. And what about MAGA? Isn’t their whole thing about fear as well — using it to maintain power, justify exclusion, not just at borders but inside the country?

A. “Exclusion” is a tricky word. Immediately, I think of the Roman political career, cursus honorum: set paths to status, service, power. Today, that means crawling through elite institutions, which you and I know. Here’s the truth: meritocracies are exclusive. When people agree to let these institutions rule, they’re agreeing to a system built on exclusion.

Q. And who decides what “better” means when you talk about making the world a better place? In your technofeudal vision, who’s left out?

A. The goal should be to improve life for everyone — especially those with the least. When China embraced capitalism, the biggest gains went to the poorest. Yes, billionaires like Jack Ma emerged, but hundreds of millions escaped poverty. For the wealthy, crime is distant; for the poor, it’s inescapable. The homeless in San Francisco don’t need abstract rights —they need real care.

The Left often enables suffering in the name of freedom, refusing to intervene even when people are mentally ill or addicted. That’s not compassion — it’s neglect. Meanwhile, the Right, repulsed by this “false empathy,” rejects empathy altogether. That, too, is a mistake.

The problem isn’t empathy, but when it’s fake. It creates dependency and chaos. Orwell saw this tension within the Left as far back as the 1930s while in Barcelona. Whenever the Left strays from its values, the question pops up again: is that flaw inherent, or is it something that could be reformed and purified of its darkest and most cynical elements? That question still haunts both sides today.

Q. All right! Let’s leave it here.

A. All right. This was a great pleasure.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.