Borges’ fictitious tale becomes reality

A new project led by writer Jorge Volpi brings together 20 authors under the age of 40 in the reinvention of a work that speaks of an inexistent civilization

The First Encyclopedia of Tlön speaks of all that is known about Tlön, its geography, customs, gastronomy, mindset. The citizens of Tlön, the book tells us, are more interested in psychology than philosophy and rather than moving in the pursuit of Truth, they move in pursuit of Amazement. In some of the languages of Tlön there are only verbs, no nouns. In Tlön, there are live transparent tigers and towers of blood. But perhaps the most notorious fact is that in Tlön, a radical idealist philosophy reigns. Ideas and language hold more weight than reality itself. In fact, its residents don’t subscribe to the existence of the objective present nor reality. If someone forgets something, that something ceases to exist. Following this reasoning, the legendary encyclopedia has recently returned to existence within our tangible reality.

Tlön is a fictitious planet, created by a 15th century secret society named Orbius Tertius, “led by a dark man of genius,” which guided the writing of the encyclopedia of the made-up world. A game that wound up becoming a monumental project, carried forward by different generations, that has covered more and more territory. The very idea of Tlön begins to take over terrestrial reality: “The world will be Tlön.”

We also know that, like a set of Russian nesting dolls, the idea of Orbius Tertius as the creator of Tlön was born from a story by Jorge Luis Borges. Tlön, Uqbar, Orbius Tertius, which was included in Borges’s collection Fictions (1944) after being published by a literary journal. “I owe the discovery of Uqbar to the conjunction of a mirror and an encyclopedia,” begins the Argentinian writer. In the tale, Borges finds a reference in a tome to the country of Uqbar, a nation that not only cannot be found in any other book, almost as if it did not exist, or that it only existed within that singular volume. One of the heretical leaders of Tlön comments that, “mirrors and copulation are abominable, since they increase the number of men.”

With time, the author and his inseparable friend and partner in obsession Adolfo Bioy Casares discover, through their found volume of the First Encyclopedia of Tlön, that Uqbar is a country on the planet of Tlön, a world that was invented by the aforementioned secret society of intellectuals and philosophers.

“Now I held in my hands a vast methodical fragment of an unknown planet’s entire history, with its architecture and its playing cards, with the dread of its mythologies and the murmur of its languages, with its emperors and its seas, with its minerals and its birds and its fish, with its algebra and its fire, with its theological and metaphysical controversy. And all of it articulated, coherent, with no visible doctrinal intent or tone of parody,” writes Borges, in a most Borgian manner.

“Fiction invents all things, and it also invents books,” observes Juan Casamayor, publisher at Páginas de Espuma. This celebrated tale reflects on the intricate loops that bind reality and fiction, and, in the case of the fictional encyclopedia it features, explores how books can shape reality. In an era dominated by fake news, we are acutely aware of how various forms of information can influence perceptions of truth.

Reality and fiction blur further with Páginas de Espuma’s ambitious project, spearheaded by Mexican writer Jorge Volpi: the Primera Enciclopedia de Tlön (in English, the First Encyclopedia of Tlön). This work, inspired by Borges, imagines itself as Volume XI of the fictional encyclopedia mentioned in his story, now materialized in our tangible world. Much like Lovecraft’s Necronomicon or Chambers’ The King in Yellow, a fictional book steps out of its literary origins and becomes part of our reality.

“This book can be read in three ways. Literally, as a facsimile of the first known copy of the Encyclopedia of Tlön. Metaphorically, as the product of a secret and benevolent society created with the purpose of inventing a country. Or fantastically, like an anthology of short story writers under 40, one from each Spanish-speaking country,” says Volpi.

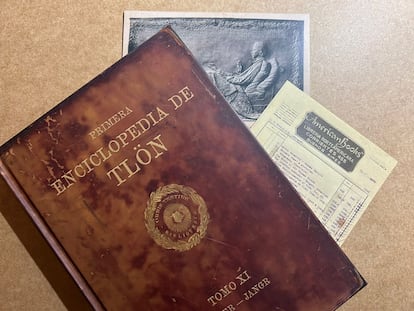

In the original story, the volume is referred to as A First Encyclopaedia of Tlön. Vol. XI. Hlaer to Jangr — this is the book Borges discovers and which has now been meticulously reproduced exactly as it is physically described in the fiction. This replication was carried out with exceptional care and precision, though it falls short of the claimed 1,001 pages — yet the pagination, as if by some magic, still suggests otherwise. The idea for the project was proposed by Jorge Volpi to Juan Casamayor, who assigned Paul Viejo to handle the editorial process. In a playful homage, the contributors are credited in the volume under pseudonyms: George Foxes, Paul Oldman, and John Manor House.

“The idea fit perfectly because we are turning 25 years old and this could be a flagship book for a publishing house dedicated to short stories, that got its start being very much dedicated to anthologies. The book of all books created by the short-story writer of all short-story writers, Borges,” says Casamayor. “Even so, at the beginning I didn’t believe we would be able to do it, because it required very complex reproduction work.”

To create this so-called “real” version of the volume, they enlisted the help of 20 short-story writers under the age of 40, each hailing from a different Spanish-speaking country. Some were already well-known, while others were discovered through a systematic search. Among them were Spain’s Irene Reyes-Noguerol, Chile’s Paulina Flores, Argentina’s Marina Closs, and Guatemala’s Rodrigo Fuentes. These writers were given complete creative freedom to craft an encyclopedia entry on a Tlönian subject, drawing inspiration from Borges’ original story. “An encyclopedia, by its very nature, is already an anthology; it doesn’t encompass all of reality, but selects certain things while omitting others,” reflects Viejo. “To create it, we carefully studied both the content and the form,” he adds.

Indeed, the volume meticulously recreates the appearance of the book as described by the Argentine master, paying close attention to every detail. It has the “vintage” look of an Encyclopedia Britannica (which Borges studied with great intensity), with stained pages, tightly packed text (“almost impossible to read for pleasure,” says Viejo), illustrations, and even lost objects tucked inside — such as a postcard and a receipt from the American Books bookstore on Calle Corriente 455 in Buenos Aires, a place Borges often visited. Among the fictitious books listed on the receipt are fictitious works by Milton, Joseph Conrad, and Thomas Carlyle — writers cherished by Borges.

Perhaps this edition of the so-very fictitious book is a first incursion of Tlön into our reality. Perhaps soon, the world will be Tlön.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.