Eighty years of ‘Animal Farm’: Why we keep reading Orwell

The British writer was satirizing Stalinism in his novel, but the story is a warning against any form of totalitarianism and a defense of independence, intelligence and, above all, humanity

August 17, 2025, marked exactly 80 years since the first publication in the UK of Animal Farm, by George Orwell, who died in 1950 of tuberculosis at the age of 46. As his work is honored, the question arises whether any author writing today will still be remembered and celebrated in 80 years’ time — in other words, the year 2105.

The question forces us to imagine what our future will look like. But try as I might, I can’t conjure up a picture of what’s ahead. First, of course, because the future is unknowable terrain, and second, because, given the accelerated transformations brought about by technology, forecasts are becoming increasingly short-term. With such a limited capacity for predicting the future, it’s hard to imagine what type of book written today could possibly be relevant in the year 2105. Not only that, but with humanity facing a devastating climate crisis which looks unlikely to go into reverse, what kind of life will even be possible in 80 years?

We can only turn to the past, which we do know about, and ask ourselves the same question but from a different angle: why is Animal Farm still commemorated? Why not do the same with other books published that same year that are also still read today, such as Brideshead Revisited, by Evelyn Waugh, or Sparkling Cyanide, by Agatha Christie? Why, in short, is Orwell so resistant to the passage of time?

The obvious answer, which also applies to Cervantes and Virginia Woolf, is that they tell us truths that continue to be relevant in 2025. This can mean two things: either that our societies have not changed substantially since 1945, or that Orwell’s writing is not as time-specific as it might seem at first glance given that his view of his era’s politics comprises the backbone of his work.

If we make a cursory comparison between 1945 and 2025, we can see at least one radical difference. That year was a key year for the 20th century when the foundations for the world we live in today were laid. In 1945, the Second World War ended and humanity, while splitting into two blocs, embarked on a path of physical, political and moral reconstruction. To do so, it needed to equip itself with new tools that would help to prevent a repeat of a conflict that violently ended the lives of between 40 and 50 million people, according to the most conservative estimates. As much as our contemporary world is marked by wars and tension, quantitatively, the scale is incomparable.

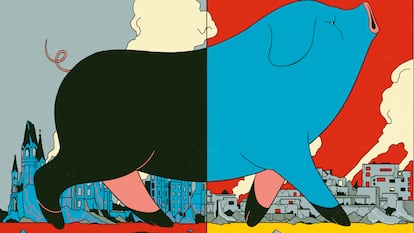

But Animal Farm was inspired by the previous decade, when at the end of 1936 Orwell travelled to Spain to fight fascism in the Spanish Civil War. During that experience he saw first-hand how the long shadow of Josef Stalin reached the Republican trenches in the form of purges, as he described in Homage to Catalonia. A few years later, in November 1943, Orwell began writing his satire of Stalinism in which the animals of a farm, led by a group of pigs, expel the oppressive farmer and take command to establish what begins as an egalitarian utopia and ends up a regime of terror.

When Orwell finished the manuscript and attempted to publish it, he received one rejection after another from important publishers such as Jonathan Cape and T. S. Eliot, working for Faber & Faber. The writing, it seems, was too stark and critical of the man who, at the time, was Britain’s main European ally against Hitler. The book was finally published by Secker & Warburg just two days after Japan announced its unconditional surrender, marking the unofficial end of World War II, and making its author an overnight celebrity.

But in Animal Farm, Orwell does not simply ridicule the behavior of an evil leader like Stalin. To do so literally, with names and surnames, would surely have prevented the book from transcending its era. What the author does is much more intelligent and subtle; he lays out the journey of a political ideal that becomes disfigured to the point of criminality. He depicts through his farm animals how a utopia is dismantled, with language as the first stepping stone. Orwell focuses on the use of language by warning us that, in order to dominate human groups, manipulation of language is key, an idea he expanded on in his novel 1984.

Language is what makes a community possible and, long before we realize what is happening, totalitarianism starts to destroy the meaning of core words, thus dissolving the common space — the sphere of shared meaning. The words are resignified and the next thing those in charge ride roughshod over the consciousness of individuals who are no longer capable of recognizing the community to which they previously belonged.

This concept is represented in the book by the seven commandments for the animals. They are written on a wall to serve as a moral guide for the new society. But, as the leaders become corrupt, the commandments are surreptitiously modified to legitimize that corruption. Thus, the fifth commandment, “No animal shall drink alcohol” ends up as “No animal shall drink alcohol excessively.”

The fact that we witness similar strategies in politics every day would explain, in itself, the validity of the book. Where we once heard, “We will always hold primary elections because we are democrats,” we now hear, “We will elect whoever suits the leader of the party because that is the best for everyone.”

Having described the path of totalitarianism so precisely, the book functions today as a warning, just as it did in 1945 and, with any luck, as it still will in 2105. These are the signs that herald authoritarianism: be careful, Orwell seems to be telling us. They are signs that proliferate today in all corners of the globe.

It is also necessary to ask how anchored Orwell’s work is to its time and the answer is obvious: from his first articles and essays, we perceive a man strongly concerned about the injustice of the appalling living conditions in London’s hostels for homeless people, which he himself experienced. And also the injustice of the capitalist stratagem behind a Parisian newspaper called The Friend of the People.

But, from my experience as a reader, I would say there is something fundamental in his writing that does not necessarily emanate from his talent as a writer, nor from his bold reporting or his courage as a whistleblower. Rather it is his humanity.

If Orwell is issuing a political warning, he is also enlightening us from a human point of view, particularly with Animal Farm. This is done through intelligent, meticulous and concise prose. Orwell is endowed with a powerful capacity for observation, but, unlike most, he also has a rare common sense that allows him to immediately detect where things are going wrong. It is a common sense that he applies not only to his observations of the world, but to himself. We see it for example when, acting as an imperial police officer in Burma (now Myanmar), he has to kill an escaped elephant while 2,000 natives watch him. He is fully aware of his role as a member of an oppressive force and a dominant caste that he will end up despising.

That common sense is coupled with precise prose to tell us the truth of the facts as they stand when no one is manipulating our view of them; facts without ideological layers, without social conditioning, without cultural filters. In the privacy of our home, we watch the starvation in Gaza and we say to ourselves: this is genocide.

Irene Lozano writes about this in her fabulous prologue to Orwell’s complete essays published in 2013 — which include Shooting an Elephant — in which she reminds us of Hannah Arendt’s description of Orwell’s unquestionable and inescapable truth as “the modest truths of facts.” Orwell cast his gaze on these sometimes minuscule truths, knowing that defending them would end up pitting him against powerful people who, in many cases, were his own people.

He criticized British imperialism as soon as he had sufficient experience and judgment. He criticized Rudyard Kipling for upholding that imperialism while applauding him as a writer. He fought against fascism in Spain and abroad. He defended a model of democratic socialism that pitted him against the British intelligentsia. And he relentlessly attacked Stalinism despite the fact that Russia was his country’s main ally against the Nazis and that Stalin was the benchmark of the international left.

With his frank vision of reality and clean use of the English language, Orwell distils the unfathomable to something recognizable. In all his writing, the ethical nucleus from which it emerges is revealed. And that ethical core is the very heart of the human condition. We read Orwell because we recognize in him an equal who is capable of expressing the essential truth of things, even if it bothers us. Even if it loses advertisers. Even if it loses voters. Even if he loses comrades in the trenches. It is the truth as it is and as anyone, in the privacy of their home, is capable of recognizing. Orwell represents, in a way, a longing for an enormous number of people. Many of us would like to have his acuity as an observer, his clarity to discern, his courage to raise his voice, his talent as a writer, his intense human baggage, his incorruptible spirit and even his contradictions.

In my opinion, Orwell is still read for the same reasons that Shakespeare is still read: because, apart from the changeable and changing nature of each era, from natural catastrophes to empires that rise and fall, we have the human condition, which has proven to be durable. The fear of being struck by lightning in the middle of the Paleolithic period is just another form of the fear felt right now by Gazans who don’t know where the next bolts of lightning will strike: whether from a drone, a missile, or an automatic weapon. It is the same unbearable emotion that those kidnapped by Hamas have been experiencing for so many months now.

Hope is the same emotion now as it was in the Renaissance, as is the lust for power and wealth, abuse and domination, compassion and pity. We are, essentially, the same as we have always been. Whoever publishes a book this year and hopes it will last for another 80 will do well to sharpen their scalpel and dissect the only thing we know for sure will remain of us: our human condition.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.