‘1984’: How George Orwell’s Big Brother was born during the Spanish Civil War

Spain would represent a major point of rupture in the British author’s life. The novel takes place in London, but its seeds were planted during armed conflict in the streets of Barcelona

In late October, speaking about Ukraine, a Russian legislator noted, “The special military operation not only takes place on the battlefields, but also in people’s minds, in their souls.” That same week, it was discovered that the Chinese government had set up “police stations” in nearly 20 countries to monitor its citizens abroad. At around that time, Amazon introduced an update of Astro, its household robot, and received complaints because, as one user explained, “its sharp tracking system for monitoring people was almost creepy.”

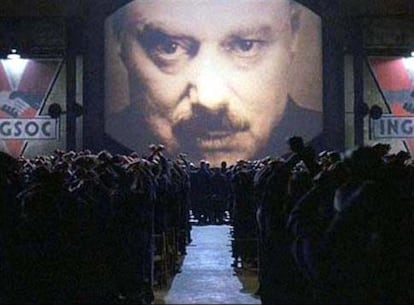

Not a decade, year or even week goes by without something happening that brings us back to George Orwell’s novel-world 1984. The book’s power is such that its concepts – such as Big Brother and the Thought Police – are familiar to millions of people who haven’t read the book.

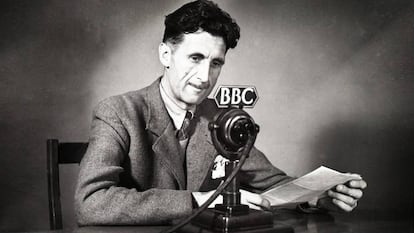

1984 can be (and is) read as a dystopia, a prophecy, a satire, a political thesis, a science fiction novel, a psychological thriller or horror story, a gothic nightmare, a postmodern text and a love story. It is also one of the world’s most famous works of fiction. Journalist Dorian Lynskey’s book The Ministry of Truth: The Biography of George Orwell’s 1984 discusses the novel’s origin, development, and impact. In particular, he shows how Orwell’s experience in the Spanish Civil War became the driving force behind the tome’s creation.

Spain: Orwell’s ground zero

“History stopped in 1936,″ Orwell told his friend Arthur Koestler, the author of Darkness at Noon. He was referring to the moment when totalitarianism emerged in Europe. At that time, “history stopped, and [1984] began,” Lynskey argues.

Spain represented a moment of rupture in Orwell’s life, his ground zero. The novel takes place in London, but its seeds were planted in the streets of Barcelona during the Spanish Civil War. “Orwell arrived in Spain full of revolutionary optimism,” but after months on the Aragon front, “the atmosphere of terror that he experienced in Barcelona in May 1937 is what he later conveyed in 1984,” Lynskey explains in a video interview.

The specific moment occurred when the communists, following the Kremlin’s orders, revolted against their erstwhile anarchist allies. Five days of infamy and violence ensued, leaving a thousand dead. Orwell witnessed that event firsthand because he fought in the ranks of the POUM (the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification), a Spanish anti-Stalinist communist group. In those frenetic hours, suspicion cast a pall over every greeting; he knew about the persecution and murder of his comrades. He also understood that his life and that of his wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy (who was also in the city), were in danger. The English couple was lucky: the pair fled Barcelona and survived the repression, but they never forgot it.

The fuse was lit on May 3, when assault guards, sent by the communists, seized the anarchist-controlled Telefonica building. The Continental Hotel – a hub of fighters, journalists, hustlers and spies – was located on the Ramblas nearby. In that hotel, Orwell heard an agent of Stalin’s secret police (nicknamed Charlie Chan) “report” that the outbreak of violence stemmed from an anarchist coup against the Republic in an effort to help Francisco Franco’s troops.

Paranoia and conspiracy

“It was the first time I had seen a person whose profession was telling lies,” Orwell wrote in Homage to Catalonia. The tensions between different political groups did not surprise Orwell, Lynskey notes, but the calculated telling of lies did. One of those lies was that the Communists had managed to “dismantle” a network of anarchist traitors who had been communicating – via secret radio stations and messages written in invisible ink – with the Fascists about assassinating Republican leaders.

During the communist purge, Barcelona had a nightmarish climate and, as Orwell put it, became “a lunatic asylum.” It was a place where paranoia, slander and rumors created such a toxic atmosphere that even those who weren’t involved in the intrigues saw themselves as conspirators.

“Orwell had been driven to Spain by his hatred of fascism, but he left six months later with a second enemy… the ruthlessness and dishonesty of the Communists shocked him,” observes Lynskey. He adds that, depending on the moment, the Animal Farm author found his experience in Spain to be “thrilling, boring, inspiring, terrifying, and, ultimately, clarifying.”

Orwell believed that truth was the most important thing, even if it was unpleasant. When he arrived in London, the writer looked for a place to publish what he’d seen in Barcelona. That’s why he considered it to be “a betrayal and a shock that he was hindered in that possibility, because editors who were his friends argued that describing those events, even if they were true, could favor Franco’s troops and fascism,” Lynskey says.

But all Orwellian writing emphasizes the value of lived experience. Thus, the political lies told in Spain and the concealment of the truth in the United Kingdom changed his perception of reality and planted the seed of inspiration. “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism,” Orwell declared in his 1946 essay “Why I Write,” just a short time before he began working on the novel.

Then, on Scotland’s Island of Jura, Orwell wrote 1984 in a house he was borrowing from his friend David Astor, a journalist at The Observer. He chain-smoked as he did so, even though he was weakened by bronchitis that eventually became tuberculosis. Orwell also kept a gun close at hand because he was convinced that a member of the English Communist Party might show up there to kill him. The novel was published in 1949.

A codex of fears

Since then, 1984 has become a cultural icon with almost infinite implications. According to author Anthony Burgess – who wrote A Clockwork Orange, a novel indebted to Orwell’s masterpiece – the book represents “an apocalyptical codex of our worst fears.”

Lynskey notes that 1984 “remains the book we turn to when truth is mutilated, language is distorted, power is abused… That’s why it works at any time.” In The Ministry of Truth: The Biography of George Orwell’s 1984, he describes how the book has been interpreted in different ways over time. During the long Cold War, it was read as an anti-Stalinist work, and indeed many were imprisoned or executed if they read or distributed it. Eastern European political prisoners found it to be a literary miracle that prompted them to excitedly ask Western journalists, “How could Orwell know all this?” They were astonished that the book could so accurately explain the conditions in which they lived, how they felt, how they were watched.

Lynskey cites the specific case of Timothy Garton Ash, who met many clandestine Orwell admirers during his travels in Eastern Europe. “How did he know?” they asked him (Garton narrated this experience in a piece in The Observer in 2001). As Lynskey explains in his book, “Well, he knew because he paid attention. He observed communist behavior in Spain, he listened to exiles, he read every book he could.”

In the 1970s, 1984 was interpreted as a warning against the resurgence of new fascisms, as in the cases of Chile and Argentina. In the 1980s, the novel seemed to augur a new danger: invasive technology.

Power and hope

At the end of 1983, the critic George Steiner wrote “never has any single man or stroke of the pen that struck a year out of the calendar of hope,” referring to Orwell’s work. Inevitably, 1984 came marked by the old novel, and the year did not disappoint. One of the documents that best defined Orwell’s dystopia was the Ridley Scott-directed advertisement for Apple’s launch of the Macintosh computer. Introducing the commercial, Steve Jobs declares, “Apple is the only force that can ensure their future freedom.” Before cutting to a video of company partners and workers, Jobs poses the question: “Was George Orwell right about 1984?” In that vein, Lynskey cites essayist Rebecca Solnit in his biography: “Maybe Apple’s 1984 ad is the beginning of Silicon Valley’s fantasy of itself as the solution, not the problem — a dissident rebel, not the rising new Establishment.”

As in the past, today 1984 serves as “a vessel into which anyone could pour their own vision of the future,” Lynskey emphasizes. These days, Orwell’s novel is perceived above all as an allegory about fake news and the alternative realities promoted by governments such as Donald Trump’s, which featured such Orwellian characters as Rudy Giuliani. Indeed, at a press conference, the former president’s lawyer stated that “truth is not truth.”

“1984 is a multipurpose book, but above all it is a book-alarm, designed to wake us up, because it speaks of the fragility of truth in the face of power,” Lynskey reflects. We have been warned. In June 1949, just months before he died, George Orwell informed his publisher Fredric Warburg that “the moral to be drawn from this dangerous nightmare situation is a simple one. Don’t let it happen. It depends on you.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.