The Englishman whose photos captured the smiles of the Spanish Civil War

Alec Wainman documented life near the front for two years, but his work was lost for decades

The young man looking shyly at the camera from behind his round glasses in Barcelona is Alec Wainman, an idealistic Englishman who came to Spain in September 1936 at the age of 23 to drive an ambulance for the British Medical Unit, one of the many international volunteers who fought against General Franco on the side of the Spanish Republic.

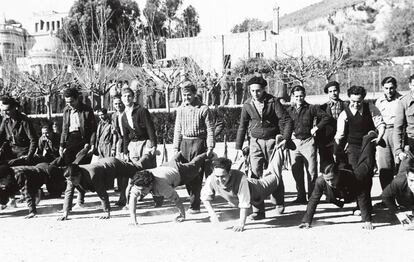

A man who described himself as “ an apolitical Quaker”, Wainman documented the Ebro Front and the arrival of the US volunteers from the Lincoln Brigade in Barcelona with his Leica camera, as well as making portraits of civilians whom he coaxed into smiling.

Wainman left Spain in August 8, 1938 after contracting hepatitis, taking with him rolls of film hidden among medical provisions to avoid the republican censors. His cache amounted to 1,650 photos, only a few of which came to light over the years. Faithful to his antifascist principles, Wainman went on to serve in World War II, working with British Intelligence.

His involvement in conflict was something of a family tradition. His great-great-grandfather was asked by George Washington to use his skills as a blacksmith to make a chain to stop British ships coming up the Hudson River, while his great-grandfather fought in the cavalry against Napoleon, and his own father was killed in action during World War I.

Wainman returned to civilian life as a lecturer on Slavic studies at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, waiting for Franco to die before handing over his photographs to a London publisher. “There was no agreement and the publishing house went bankrupt shortly afterwards,” explains Wainman’s son, Serge Alternês (a pseudonym for John Alexander Wainman, born in Vancouver in 1961).

The photos went astray and Wainman was struck down with Alzheimer’s before dying in 1989. “Almost 40 years later, I located the photos thanks to a call from a former employee at the publishing house,” says Alternês. “She had kept the collection in a suitcase. It was a great relief.”

In 2015, Alternês managed to persuade a small Canadian publisher to put together a book that is now being published in Spanish. Entitled Almas vivientes (Living souls), it is a collection of 210 photos, along with prologues by various academics including the hispanist Paul Preston and the director of the Cervantes Institute, Juan Manuel Bonet. The book also includes excerpts from Wainman’s diary that his son stumbled across 12 years ago.

“I felt somehow that I was collaborating with my father again, something we were unable to do during his illness,” he says.

The collection includes photographs of the doctors and nurses who tended to the injured from the international brigades in field hospitals on the Ebro Front. Wainman told his son that he often needed an hour to get the right picture.

The book is filled with anecdotes, such as the time when Wainman gives another ambulance driver a a can of water instead of gasoline due to his poor Spanish skills. Another story details his first contact with the Catalan Communists. “The men at the checkpoints had long beards and looked like Ali Baba and the 40 thieves,” he wrote in his diary. He also humorously recorded his first experience with the traditional wine pitcher in a Catalan village. “The novice will choke the first time around, so it is advisable to practice with white wine as opposed to red to avoid ugly stains on clothes,” he noted.

Wainman did not shy away from speaking about the horrors of the war, however, such as the arrival at the hospital of a Moroccan prisoner of war with “a thigh wound infected with gangrene big enough to fit a fist in, and smelling unbearably bad.”

In April 1937 he was transferred to Madrid, where he witnessed the bombing of the Gran Vía. “The people of Madrid continue to be exposed to bombardment and grenades that have emboldened them to the very limits of fear,” he wrote. That year Wainman became more deeply involved in the conflict after being named head of the English and American Press Department by the Republican government.

According to a friend, Wainman had a “friendly face and sweet smile” which no doubt helped him capture upbeat images of soldiers, nurses, farmers carrying wood and children with their fists in the air. “He had a special connection with them because he spoke to them in Spanish,” says Alternês.

However, among the last photos, there is one of a hospital train carriage with three layers of bunk beds and the injured looking down at the camera with miserable expressions on their faces, their plates lying empty on the floor. These were the faces of defeat, something that would come to pass eight months later.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.