Eighty years on, reconciliation in Guernica

EL PAÍS brings together a survivor of the Civil War bombing with descendants of two of the Germans responsible

On Tuesday, 80 years after the bombing of Guernica at the height of the Spanish Civil War, three men with a close connection to that terrible event met in the Basque town: Luis Iriondo Aurtenetxea, Dieprand von Richthofen, and Karl-Benedikt von Moreau.

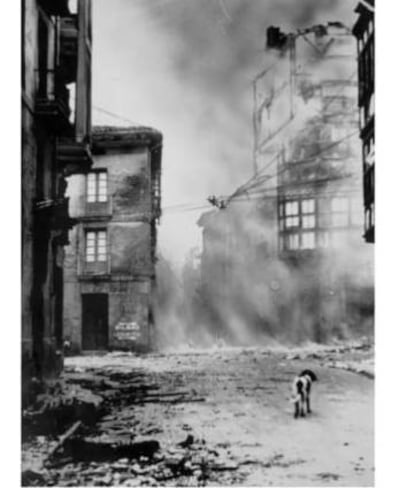

The first, now aged 94, is one of the very few survivors of the aerial bombardment on April 26, 1937 that left the undefended market town in ruins, killing a still unknown number of people estimated at between 200 and 1,650. Iriondo’s two German friends, are relatives of two of the men responsible for the massacre: Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen, the head of the Condor Legion, army and air force units sent by Hitler to support General Francisco Franco’s military uprising, and Rudolf von Moreau, one of the pilots who dropped the more than 7,000 bombs over the course of three hours that fateful day.

We all knew that the Guernica bombing was a war crime Dieprand von Richthofen, nephew of German field marshall Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen

EL PAÍS had brought the three men together for an emotional reconciliation – it featured hugs and drawn-out handshakes – during the week-long commemorations being held in Guernica that will include talks, concerts and public readings. Among the guests are the mayor of the Polish city of Oswiecim, remembered by its German name of Auschwitz, along with survivors of the US atomic bomb attack on Nagasaki, who accompanied Luis Iriondo as he read out his account of the bombing of Guernica.

This is the second time Dieprand von Richthofen has been to Guernica. His father was a pilot who served under Wolfram von Richthofen. “My father knew him well, but he didn’t like him. He worked very hard and was ambitious when it came to his military career. But he was, above all, terribly loyal to Adolf Hitler and would never have been able to betray him.”

Dieprand von Richthofen had read about his uncle at school, but he says it was only in 2000, when the whole family gathered together to face up to its Nazi past that he learned about his uncle’s involvement in the massacre. “We all knew that the bombing was a war crime,” he says.

Von Richthofen says he feels no guilt about what his uncle did, but admits that his surname is a heavy cross to bear, both for him and his son, now aged 32. “In 2012, he read an article about Wolfram von Richthofen and had the same feeling as me. He felt he was being mentioned. That is why we first came to Guernica.”

He admits that during that first visit he was terrified. “The guilt was there, part of me. But when I saw how the people of Guernica received me I realized that there was no bitterness, and much less a desire for revenge. On the contrary, they wanted reconciliation. And today, to see how Luis Iriondo, a survivor of that horror that a member of my family took part in, has welcomed me with open arms, has been liberating.”

Karl-Benedikt von Moreau, aged 57, lives in Germany and is visiting Guernica for the first time. His uncle, Rudolf von Moreau, was a senior officer in the Condor Legion and took part in the bombing of Guernica. In 2003, he and his brothers wrote an open letter to the people of Guernica expressing their solidarity and pain with the survivors and relatives of the victims.

“My feelings are very strong, this is something that churns you up… but the most amazing thing is seeing how much people here want reconciliation with Germany, to shake hands, to hug each other. It is very moving,” he says.

“When I learned that my uncle had taken part that day, and that he had bombed Bilbao and other locations on the northern front, it had an impact on me. I want to accept that past, assume my responsibility. It is very difficult, it is sad, but I want to help find a better, peaceful, future for Europe.”

‘I was afraid of being buried alive’

This is Luis Iriondo’s account of the events of April 26, 1937, read out at the Teatro Liceo in Guernica as part of the city’s commemorations of the bombardment 80 years ago.

“I was aged 13. My friends and I ignored the air raid sirens; we’d been at war for eight months and we were tired. We didn’t even bother going to the air raid shelters, we got bored there! That day the market was being held on the main street. That was where we heard the first bombs. People ran for the shelters. Somebody carried me up and took me to the very bottom of one of them. It had a dirt floor and the walls were damp. There was no light and no oxygen to breathe, and I was terrified of being buried alive. What’s more, the day before I had worn my first long trousers and my mother told me not to dirty them under any circumstances. But I did. I ran to the entrance of the shelter to breathe. I wanted to say a prayer we had been taught in school, but I couldn’t.

When I left the shelter I was terrified. The whole town was burning. Behind the Santa María church I took the road toward Lumo. The whole time I was wondering what had happened to my parents and my brothers and sisters. I reached a gully and there was a pile of bodies, one of them was a friend of mine who died there. I sat down with another friend on the hillside, watching Guernica burn. He said to me, without any emotion in his voice: “Look, in that house they have just pulled down was my aunt, who is deaf and my grandmother, who is paralyzed. When we got to Lumo, somebody, I don’t remember who, gave us a cup of milk and some straw to sleep on. I fell asleep immediately. Suddenly, in the night, I woke up. Somebody was calling me. It was my mother. She had spent the afternoon and all night looking for me. My brothers and sisters were fine. I was the only one missing.”

English version by Nick Lyne.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.