Repression and war boost sales of Orwell’s ‘1984’ in Russia

Readers seek parallels and answers to the current situation in dystopian stories, self-help guides and classic works about armed conflict and authoritarianism by authors like Tolstoy and Thomas Mann

George Orwell’s 1984 is not just a simple story about state surveillance of a citizenry. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s official description of his war on Ukraine is, “a special military operation to defend the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics.” On several occasions, Putin said “it was obvious that confrontation was inevitable…” Last December, he elaborated, “The only question was when... and better today than tomorrow.” Putin even accused the Ukrainian government of being the reincarnation of Nazism. But Putin’s domestic repression has led to surging sales of books that tell stories uncomfortably similar to the lives of Russians today – books like 1984. In the third chapter of his famous dystopian novel, Orwell wrote, “The enemy of the moment always represented absolute evil, and it followed that any past or future agreement with him was impossible.” This warning against repression and neologistic language has been widely available in bookstores for 75 years.

For a society confused by the bloodshed in Ukraine, the most popular books in 2022 were self-help guides, stories about 20th-century totalitarianism and tales about the ravages of war. According to LitRes, the largest digital bookstore in Russia, the two most popular works were 1984 and Olga Primachenko’s To myself gently: A book about how to appreciate and take care of yourself. Sales of both titles increased by 45% and 83%, respectively, over the previous year. Orwell’s sales began trending up in 2021 following the arrest of activist Alexei Navalny and the subsequent persecution of dissenters and independent media outlets.

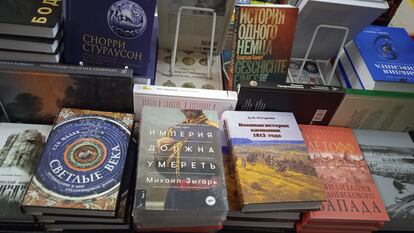

On a St. Petersburg street named after poet Nikolai Nekrasov, there are several independent bookstores, including one called All Free (Vse Svobodny). Its front window bears an old Soviet-era slogan – Peace to the World – a play on the Russian words Miru-Mir. “Before, we used to sell more anthropology, philosophy and art books. Now, it’s books on politics, history and biographies about very specific periods in history, such as the fascism of the 1930s and 1940s,” said Liobov Beliatskaya, one of the bookstore owners.

“We also sell many other books loosely related to war, both nonfiction and fiction,” said Beliatskaya, citing anti-war writers like Heinrich Mann and Thomas Mann, two German brothers driven from their country by Nazi oppression. Russian literary icon Leo Tolstoy is also enjoying a resurgence in popularity.

“Tolstoy’s essays on the Russo-Japanese war of the early 20th century are big sellers lately,” said Beliatskaya. Early in the invasion of Ukraine, Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska posted messages of peace on social media, one of which quoted Rethink Yourselves, Tolstoy’s open letter on the Russo-Japanese war. “Again the war. Again suffering that no one needs, suffering that is absolutely unnecessary. Once again the deception, once again the bewilderment and the brutalization of everyone.”

“We received a new translation of 1984 this year, but to be honest, it’s not very good. It has always sold very well, like all the dystopian novels,” said Beliatskaya. Her opinion is shared by the bookseller at nearby Na Nekrasova, a bookstore specializing in old editions. “Orwell sold just as well in 2000 as in 2020 – dystopia has always been very popular,” she said, declining to give her name. “I’d rather not comment on politics.” Surrounded by books about Tsarist Russia and Soviet-era trains, she told us that sales “dropped by 40% at the beginning of the military operation… People were worried and weren’t sure what the future held, but sales later rebounded.”

Varlaam is a 20-something Russian who discovered 1984 last year. “I didn’t think [what I was reading] was possible. I felt two emotions: surprise and fear,” he said. The young man identifies with the book’s Proles, a social class at the bottom of a society controlled by the Thought Police. Varlaam tries to stay out of politics. “I try to detach from all that and focus on myself,” he said.

There are striking similarities between the “Newspeak” language used in 1984 and the euphemisms used by a government that describes its invasion as a “special operation.” State-controlled media reports dehumanize the Ukrainians by using words like “eliminated” and “suppressed.” It hasn’t gone unnoticed by Varlaam. “They are trying to change the meanings of words, and they are succeeding because people are not well educated.” The young man is now reading The Witcher, a series of fantasy novels by Polish author Andrzej Sapkowski. He can’t help but think of Ukraine when reading the vivid descriptions of wartime horror and evil in the novels.

If Orwell’s 1984 is where Russians go for answers about authoritarianism, Olga Primachenko’s To myself gently is where they go to detach from reality. A young woman named Yevgenia who read the book told us, “I think it’s very relevant in these times. You have to take care of yourself when the world is collapsing around you… One person cannot change international politics or argue with a dictator, but you can improve your own life.”

Searching for answers in Defying Hitler: A Memoir

Russians are also drawn to memoirs by those who witnessed the rise of totalitarianism nearly a century ago. “Some of these books went unnoticed for years but have now become bestsellers,” said Beliatskaya from the All Free bookstore. “Books like Sebastian Haffner’s Defying Hitler: A Memoir… People are drawn to historical parallels,” she said. “We can influence a political process that’s happening once again, can’t we? When history repeats itself, people look to the past for answers.”

“The story I am about to tell is the story of a strange duel. A duel between two unequal opponents: an incredibly powerful and implacable state and an unknown little citizen,” writes Haffner in the preface to Defying Hitler: A Memoir. A journalist who often criticized Nazism, Haffner escaped to Britain just in time. Written in 1939, his memoir wasn’t published until 2000, a year after his death.

Haffner’s book survived the iron-fisted censorship of the German authorities, but other books met different fates. American writer Mark Manson’s Everything Is Fucked: A Book About Hope had sections excised by Russian authorities who didn’t like its comparisons of Nazi Germany with the USSR. A footnote in the Russian edition says, “This section was removed in accordance with the law on the perpetuation of the victory of the Soviet people in the Great Patriotic War.”

Russian censorship has been expanding to other areas. “The law against LGBTQ+ propaganda has had a ‘Barbra Streisand effect’ [when censorship has the unintended consequence of increasing awareness of that information], said Beliatskaya, noting increased sales for books on these topics. “Banning something makes it more interesting.”

The Order of Words bookstore (Poriádok Slov) has a sign on the door prohibiting entry by anyone under 18. There is no hint of adult content inside – nothing you couldn’t find in any public library. The supposedly harmful content by journalist Mikhail Zygar is discreetly tucked away up on a shelf. Zygar, who has written several books on contemporary Russia, was declared a “foreign agent” by the Russian government last year. A new law not only forces blacklisted authors to identify themselves as such on social media, but they must also display a huge 18+ sticker on the covers of their books. “They sell very well,” said one of the booksellers who still dares to carry books by “foreign agents.”

It is hard to find anything by a banned author in the bookstores on charming Nevsky Avenue in downtown St. Petersburg. But there are plenty of Soviet-style calendars and books about Putin and Stalin on prominent display, as well as some about the Ukrainian war – with ultra-patriotic perspectives, of course. One such book bears the title, The Return of Novorossiya, with a “Z” replacing the “S” in Novorossiya, which means “New Russia,” the historical name used by the Russian Empire for the southern mainland of Ukraine. The Latin-script letter “Z” is one of several symbols painted on Russian military vehicles involved in the invasion of Ukraine. There’s a book about the denazification of Ukraine, also with a giant “Z” on the cover. Nearby, on another shelf, is an anthology of works by Nobel Peace Prize winner, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Its title is With Ukraine, things will get extremely painful, a direct quote from The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn’s 1973 book in which he argues that part of Ukraine is pro-Russian, but that the country should decide its own destiny without Russian interference. Even though he expressed support for Putin before he died, Solzhenitsyn’s legacy has dimmed in Russia. Just this week, a State Duma representative called for The Gulag Archipelago to be pulled from schools because it “has not stood the test of time and does not correspond to reality.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.