The day when an ordinary kitchen became a stage for the Cold War

Sixty-five years ago, two exhibitions in the USSR and US contrasted Soviet military and space might with American household appliances

Sometimes it’s not enough to quietly enjoy the upper hand – you have to flaunt it. Historical examples of such boasting include the opulence of the Palace of Versailles (the home of French absolutism), and Franco’s Valley of the Fallen monument, a constant reminder to the losing side in the Spanish Civil War of their failure. Then there’s the massive conference room table that Putin uses to keep visiting world leaders at a distance while acting out an illusion of open dialogue. These are all examples of the role of architecture and furniture in projecting an image of power.

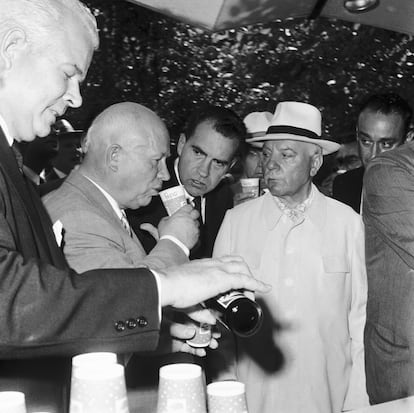

Sometimes the message is more subtle. The photograph of Soviet Communist Party first secretary Nikita Khrushchev with US vice president Richard Nixon in what appears to be a typical American kitchen is one of the strangest images of the Cold War. How did a modest, prefabricated, middle-class house become a symbol of the American and Russian struggle for technological and cultural world domination?

The story begins in September 1958 during a temporary thaw in US-USSR relations. The two superpowers agreed to hold two exhibitions in the summer of 1959 – one in New York and the other in Moscow. The Soviet exhibition in New York focused on demonstrating its extraordinary military and scientific achievements – it was a display of technological muscle. The Russian delegation arrived aboard an imposing Tupolev Tu-114 airliner, the world’s largest commercial plane. They packed the New York Coliseum with models of factories and heavy machinery, including the first nuclear-powered icebreaker ship. Amid banners adorned with images of Lenin and sculptures of Soviet workers, a special place was reserved for a replica of Sputnik 1, the first artificial Earth satellite, which was launched into orbit by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957.

Overmatched in the space race and with only one-third of the USSR’s budget for the exhibition (the US allocated $3.5 million versus the Soviet Union’s $12 million), the American National Exhibition in Moscow was radically different. Its most prominent exhibit was a geodesic dome with a gold-anodized aluminum roof, designed by architect Buckminster Fuller. His dome was touted as an “information machine” capable of handling 5,000 visitors per hour. Inside the dome, Charles and Ray-Bernice Eames, an American married couple of industrial designers, installed a complex system of seven screens that simultaneously projected Glimpses of the USA, a documentary film depicting “a day in the life of the United States.”

The American National Exhibition included a huge glass pavilion filled with a rich assortment of everyday objects and consumer goods, as well as the Circarama, a circular movie theater created by Walt Disney that projected America the Beautiful on a 360-degree screen.

Cosmetics demonstrations and fashion shows presented American teenagers walking the runway to the beat of Elvis Presley’s Jailhouse Rock. Kiosks representing freedom of the press displayed books, newspapers and magazines that visitors could browse freely, in hopes that they would be stolen and circulated throughout the Soviet Union. Convertible cars, farm machinery, sports equipment, televisions and stereos showcased American consumer products. There were even beverage dispensers with free Pepsi-Cola. The photo of Khrushchev drinking Pepsi later helped the company gain a foothold in the USSR. In exchange for Pepsi’s soft drinks, the Soviets offered the company a fleet of warships.

Harold C. McClellan was in charge of the American National Exhibition, and said its main goal was “to present to the Soviets a realistic and credible image of the United States ... to reflect how the American people live, work, learn, produce, consume and play… and to show their values and what kind of people they are.”

Splitnik: A Long Island prefab house in Moscow

When McClellan went in search of exhibition sponsors, he received an offer from a Long Island real estate developer who was willing to pay all the costs for erecting a ranch-style house in Moscow. It was a simple and affordable home that sold for $13,000 at the time (about $125,000 today), an example of the typical middle-class house that were replicated ad nauseam in every American suburb. It consisted of a wood frame, prefabricated walls and a gabled roof. The one-story rectangular floor plan measured 1,140 square feet, and had three bedrooms, one full bathroom, living room, dining room and kitchen.

Despite the home’s modest dimensions, the real estate developer’s president was confident in its propaganda value: “There is nothing you can say about free markets that will have a greater impact on the average Russian than a look at the average American home.”

To make the model home accessible to visitors, some interior walls were removed and replaced with railings, and a wide corridor split the house down the middle. This transformed a house designed for a family of four into an exhibition, through which thousands of curious Soviet visitors passed every day. A total of 2.5 million people visited the house during the six weeks it was open to the public in the summer of 1959. It was soon dubbed the “Splitnik,” a mashup of split (because of the central corridor) and Sputnik.

The kitchen debate

In contemporary architecture, the kitchen has always been a space for experimentation and technological development. It was also a central theme at the American National Exhibition, and served as a showcase for all sorts of appliances and household items. Live demonstrations showed actresses dressed as housewives preparing a complete dinner in minutes using frozen and processed foods. The Soviets gasped in awe at the “Miracle Kitchen of the Future,” a mobile display kitchen full of automatic appliances, including a self-propelled robot vacuum cleaner and a dishwasher on wheels.

The Kremlin was very conscious of the American ploy to seduce its citizens with scenes of domestic abundance. Despite all the good intentions behind the dual exhibitions, tensions inevitably surfaced. When vice president Richard Nixon officially opened the American National Exhibition on July 24, 1959, Khrushchev bluntly put down the American achievements on display. “Many of the things you have shown us are interesting, but unnecessary,” he sneered. “They are of no use.”

When the dignitaries arrived at the Splitnik home, Nixon stopped in front of the kitchen, leaned on the railing and told Khrushchev, “It’s just like our houses in California.” This was not an exaggeration – this was the typical American kitchen in 1959. It had a dishwasher, combined refrigerator and freezer, washer-dryer, garbage disposal, water heater, four-burner stove and built-in oven – all electric. The display of modern conveniences seemed to baffle Khrushchev, who mocked, “Don’t you have a machine that puts the food in your mouth and pushes it down your throat?” Nixon persisted, saying, “In America, we like to make life easier for women.” Khrushchev retorted, “Your capitalistic attitude toward women does not occur under communism.”

That was just the opening salvo in an impromptu debate between the two leaders that took place amid household appliances and boxes of scouring pads and detergent. Surrounded by journalists, top Soviet officials and interpreters, Nixon and Khrushchev engaged in a dialectical skirmish that politicized every topic of conversation.

“Your American houses are built to last only 20 years so builders can sell new houses later,” said Khrushchev. “We build for our children and grandchildren.”

Nixon countered, “American houses last for more than 20 years, but, even so, after 20 years many Americans want a new house or a new kitchen.”

“Some things never get out of date – houses, for instance,” said Khrushchev.

“Diversity, the right to choose, the fact that we have 1,000 builders building 1,000 different houses is the most important thing,” replied Nixon. “We don’t have one decision made at the top by one government official. This is the difference.”

The kitchen debate lasted 45 tense minutes and kept going for another 16 minutes in a television studio. The widely publicized tussle turned Nixon into a national hero back home. Breathless press reports exulted at how the Splitnik house had impressed Soviet visitors, who were accustomed to communal apartment blocks that often housed an entire family in one room. But on the other side of the Iron Curtain, the Splitnik was dismissed as a capitalist hoax. “Presenting this as the typical home of an American worker is like presenting the Taj Mahal as the typical home of a Bombay textile worker, or Buckingham Palace as the typical home of a British miner,” declared the son of the Soviet ambassador to the United States after visiting the house.

One thing was clear to everyone – the Cold War was no longer confined to puppet governments and wars in distant lands, nuclear warheads and space exploits. The kitchen debate had turned the home – the poster child for the American lifestyle and consumerism – into an issue of international political significance. With veritable soft power, Uncle Sam had struck a blow at the communist bear’s heart.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.