Sonita: The Afghan rapper taking on the Taliban

After fleeing her family when they tried to sell her into a forced marriage, the singer discovered rap and wrote a song against child brides that has resonated around the world

It is as flight attendants say when presenting the safety instructions that hardly of us pay any attention to: one has to save oneself before one can help others. Sonita Alizadeh survived by escaping her own family, who twice tried to sell her into a forced marriage. It was the tradition of the country where she was born in 1997, Afghanistan, which was under Taliban rule at the time. With time, she discovered other methods of survival beyond flight. She was also saved by searching inside herself, learning again to love her mother who despite living through a forced marriage herself did not seek to spare her daughter the experience. By saving herself, Sonita also saved others. She has saved many women and given many others food for thought by turning her protest into song. “I hope that having been willing to fight for my ideas and having opposed the practice of forced marriages, I have given other women the strength they need to decide their own destinies for themselves,” Sonita tells EL PAÍS from Bard College in New York, where she is studying for a degree.

Very close to where she was born, in Herat in the west of Afghanistan, lies the Shahrak-e Sabz refugee camp. Two years ago, a group of reporters from the BBC visited the camp to tell the story of Naranin. She was five years old when her parents, who did not know how to read or write, sold her for around $3,400 (€3,000). Her mother told the reporters that it was a case of survival: the money was needed to pay for medical treatment for another of their four children. It is not only in Afghanistan where girls are sold. It also happens in Myanmar, China, Syria and North Korea. They are sold ostensibly as brides, but soon become domestic and sexual slaves when they are barely 10 years old. It is a widespread problem and a result of extreme poverty and a lack of education, mixed with a profound lack of humanity.

Sonita says that more than 12 million young girls are sold as potential brides around the world every year. This is what befell her and her siblings in Tehran after the family had fled the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. Having walked hundreds of miles with her mother and her sisters, in rain, wind and snow, to arrive in Iran they found that their new home did not provide them with a brighter future. But she continued on her path, first with her family and then on her own.

Sonita’s first flight was from the Taliban, and her second was from her own mother. Escaping from the guardianship of her mother, who wanted to try and sell her for a second time in Iran, cost Sonita all of her documentation. She was forced to live as a refugee. That was when an NGO stepped in to help her. At the school for undocumented refugees in Tehran, Sonita started to sing.

She was 15 years old and she managed to express herself with joy. She used the strength she had employed to engineer her escape at the school to compose a catchy, danceable pop song. “But I realized that my message, what I wanted to say, was too sad. It wouldn’t fit into just one song,” she says from the Annandale-on-Hudson campus.

What Sonita had to say also didn’t fit comfortably into the chords of the pop music that she liked. So she decided to try rap. What she wanted to say was in reality a denunciation. She wanted to talk about the inhumane obligation of being forced into marriage, which had happened to her, her sisters and her friends and to which innumerable young girls are subjected every year in many countries the world over. “The force of rap, as well its nature of protest, made me feel good,” she says. Sonita realized that “people who listen to rap pay attention to the lyrics in the songs. They are as into the music as they are the message. They are looking for that information. They feel engaged with what they are listening to. I think rap is a vehicle for sharing transformative messages. Its strength can change attitudes.”

In the music video for her song Daughters for Sale, a bride is having make-up put on for her wedding. She is young and beautiful. She is not smiling. There is a television set on. And it is there, on that screen inside the screen, where Sonita sings: “I scream to make up for a woman’s lifetime silence. I scream on behalf of the deep wounds on my body.”

The video relates how many young women learn that they have been sold by their fathers and, knowing that Sonita escaped, the bride having make-up applied also ends up running, as Sonita sings, to escape suicide or a living hell. The video has been viewed more than 140,000 times on YouTube. The music, the lyrics and the story went viral. It even featured on television in Afghanistan. “This is the power of music; it’s international,” Sonita says. What she did in Iran also went viral in Afghanistan. “In as much as a song can go viral there,” she clarifies. Iranian filmmaker Rokhsareh Ghaemmaghami also became aware of Sonita on the web and contacted her to suggest she go further still. Ghaemmaghami wanted to make a documentary about her story. When the movie, Sonita, was distributed, she was invited to study in the United States. “I made my story known, I had the strength to tell it and it changed my life,” she says. Her courage gave her an education. Today she is studying Human Rights and Music. “That’s me, but it could be so many more women.”

With some reservation, Sonita says her sisters and her friends have not shared her good fortune and were sold. She doesn’t say if she still has contact with them. She prefers not to talk about that aspect of her life to avoid putting them at risk. But she does insist on saying that she does not hate her mother. She understands that she didn’t know any different, that she was repeating a tradition that she was taught. “I love her. Although it may not seem like it, she did what she thought was best for everyone. I don’t preach any stance. If someone wants to change their life, they have to do it themselves. Nobody can change your life for you.”

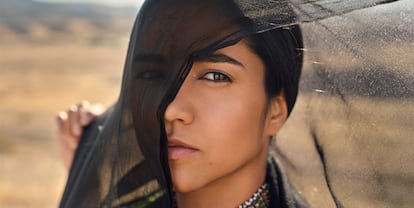

Today Sonita Alizadeh, singer, rapper, subject of a documentary and student at Bard College, is one of the 12 people featured on the 2022 Lavazza calendar, under the slogan “I can change the world” and photographed by Emmanuel Lubezki.

Does Sonita think she has played her part? “I write and sing about what is important to me; war, child exploitation. I don’t know if my music is or always will be political. I see myself more as a singer who advocates for human rights, and who uses music for that. I grew up as a child refugee and that makes you rethink your life every day. Every morning. Although I didn’t go to school, my life experience taught me a lesson: it’s essential to aim high and try to fulfill your dreams. And to do that you have to be able to dream.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.