Getting away with murder: A father’s 27-year quest to bring his daughter’s killer to justice

Jaime Saade was convicted ‘in absentia’ for shooting Nancy Mariana Mestre in 1994. Interpol tracked him to Brazil and he was arrested in 2020 but an extradition wrangle may see him freed of all charges

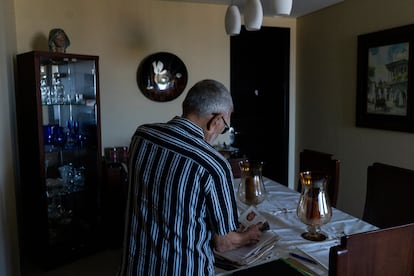

Martín Mestre, 79, has the night of January 1, 1994, imprinted on his memory. “It’s all fresh in my mind. I just push a button and reprogram the chip.” Can he push that button now? “Yes.”

The last time that Mestre saw Jaime Saade was at the door of his own house after toasting the New Year with his wife and two children. Nancy Mariana, 18, had asked permission to celebrate New Year with Jaime, whom she had been dating for some time. Mestre saw them off. “Be back at 3am,” he told his daughter. “Look after her,” he told him. At 6am he woke up with a jolt. The light in the stairway was still on and he ran to his daughter’s room. She wasn’t there. Mestre went looking for her, trying several nightclubs in Barranquilla, and he made a vow to God that if he found her, he wouldn’t be angry with her. She was nowhere to be seen. Instead, he drove to the Saade family home.

Jaime’s mother was cleaning her son’s apartment, which was built on to the house as an extension. At dawn on New Year’s Day. The floor was wet. She looked at Mestre and said: “Your daughter has had an accident; she is at the hospital.” Mestre rushed to the hospital and saw Jaime’s father, whom he knew by sight. “Martín, your daughter tried to kill herself,” he said.

Mestre spent the next eight days in the emergency room. A bullet had gone through Nancy’s head and she never regained consciousness. On January 9, the doctors said there was nothing more they could do. “We went into her room and sang her songs from her childhood, like ‘Daddy’s little girl’,” Mestre says today through tears. “Then the lines on the machine stopped jumping and we heard the sound of the beep.”

That beep marked the start of a search lasting almost three decades, conducted by a broken man: Mestre on the trail of Saade, who had gone to ground on the night of the alleged suicide attempt. “Since that day, seeing him caught is what has kept me going. It’s not an obsession, it’s a father’s duty.”

In 1996, a Colombian judge sentenced Saade in absentia to 27 years in jail for the rape and murder of Nancy Mariana. The suicide ruse was thrown out. Jaime sexually abused her and shot her. Mestre believes there was more than one person at the scene of the crime. Forensics investigators found a blood type in the house that did not correspond to either Nancy or Saade. But if there were more people involved, only Saade knows. Interpol issued an international arrest warrant in his name.

The search

Mestre knew that the chances of finding Saade were remote and he vowed never to let the case rest. As a member of the armed forces reserve, he took a military intelligence training course. His only option was to get close to the family, something he never did as Martín Mestre, despite living in the same city. He approached them through social media via four false identities he had set up: two men and two women with Arabic surnames from the Aracataca region, where the Saade family were originally from, and gradually gained their trust. For 26 years, the operation failed to bear fruit.

“The court was zealous in making sure the arrest warrant remained in force. I went there a lot. I always thought they would think ‘here’s that tiresome old man again’ but no, they were very cooperative, they consoled a father who had suffered the death of his daughter and they wanted to see justice done,” he says via video call from Barranquilla. Time was not on his side. He knew that in July 2023, Saade’s sentence would expire and if he wasn’t found before that, all charges against him would be dropped.

Toward the end of 2019, in online chats with people close to the Saade family, key words began to emerge. “Samaria” was the breakthrough. Mestre and two colonels who were working the case linked it to Santa Marta, a coastal city in the north of Colombia. Through various conversations and by pulling on the threads of the investigation the name of a tourist complex in Santa Marta came up: Belo Horizonte. What if Saade was hiding out in the Brazilian city of the same name?

Interpol investigators identified a man in Belo Horizonte matching Saade’s description. He went by the name of Henrique Dos Santos Abdala and was married with two children. The Brazilian police tracked him down. A glass he had drunk from in a bar allowed them to cross-check his fingerprints. It was Saade, more than a quarter of a century later. “I was in my office and the emotion swept over me, I started to cry. I got down on my knees and thanked God,” Mestre recalls of the moment when he was informed Saade had been arrested, in late January 2020. Extradition to Colombia seemed to be just a matter of time.

The final blow

The case reached the Superior Court of Justice in Brazil. Mestre was elated, convinced that nothing would now prevent Saade from being returned to Colombia within a matter of months to serve his sentence. Throughout all those years he had balanced his work as an architect with the incessant hunt for Saade. He separated from Nancy’s mother, who moved to Spain and remarried. He never left Barranquilla. His son, four years older than Nancy, now lives in the United States and has a daughter of his own. Mother, father and son often speak to share news about the case. They all wept, as they had done so many times before, when they learned the Brazilian court’s ruling: a tie.

Two judges had voted in favor of extradition and two against. The fifth was on leave and Brazilian justice dictates that ties always favor the accused. “They decided the fate of my daughter’s killer as through it was a game of soccer. I cried a lot. I had already cried a lot because of the case but I had never had time to mourn because I was always investigating. But I will not grow weary, I will never give up.”

Since then, Mestre has focused his energy on finding a way to reverse the court’s decision. The idea that Saade may never be sent back to Colombia has not entered his mind: “We will bring him back here and he will pay for what he has done.”

“It’s difficult,” says Bruno Barreto, the lawyer representing the family in Brazil and who is attempting to find a legal instrument to have the vote repeated. Barreto maintains that the Superior Court of Justice was wrong on at least two points. The first is a question of procedure: “It was decided on a tie, but the extradition process is not a criminal trial, it is a measure of international legal cooperation. They should have waited for Celso de Mello [the fifth judge] to return to finish the hearing.”

The second point is related to the two votes against extradition. Brazilian law states that extradition is only possible when the statute of limitations has not passed in Brazil or in the country where the original sentence was handed down. In Colombia the deadline is set for mid-2023, but in Brazil the statute of limitations is set at 20 years, making the sentence invalid in 2020. However, Brazilian law also states that if the accused commits another crime, it is considered as a repeat offense and the statute of limitations is reset. Jaime Saade also faces charges of falsification and using illegal documents to enter Brazil under a false identity, although the case has not yet gone to trial.

The two judges who voted in favor argued that the new charges should be taken into account when calculating the statute of limitations, but the two who voted against rejected this because there is no sentence in force. The Brazilian Penal Code allows for different interpretations because it provides for both possibilities. “However, the interpretation of Edson Fachin and Ricardo Lewandowski [the judges who voted against] ignored the case law of the Superior Court itself and of experts in criminal law in Brazil,” says Barreto.

EL PAÍS has unsuccessfully attempted to contact Saade, who has “no interest” in discussing the case, according to his lawyer, Fernando Gomes Oliveira. His parents have passed away and his siblings published a letter in his defense shortly after his arrest. However, Oliveira is willing to talk. He says his client “is doing well” in Belo Horizonte, where he is a businessman, and “getting on with his life.” He is awaiting trial for using illegal documents to enter Brazil but isn’t worried about a tough sentence. “At most he’ll pay a fine,” says Oliveira. Married and with two Brazilian children, he has the support of all of his family, in Brazil and in Colombia. Oliveira describes Nancy’s death as a “tragedy” in his own client’s life.

Saade’s version of events is very different to that of the investigators. In a letter written when he was in jail in Brazil last year, while the Superior Court was ruling on his extradition, Saade insisted that Nancy committed suicide. “I went to the bathroom and after a few moments I heard a shot. I went out immediately and saw her on the floor, with a lot of blood and a revolver next to her,” he says in the letter. Despite gunshot residue being found on Nancy’s left hand, which Saade bases his defense on, the suicide hypothesis was ruled out. “The investigation has grotesque inaccuracies,” says Oliveira. If Saade had intended to kill Nancy, “he would have not have taken his companion to the hospital.” The lawyer regrets that his client didn’t have the opportunity to defend himself. But he did not have the opportunity because he vanished that same night.

Saade’s sentencing in Colombia refutes his version of events. Nancy did not kill herself. The gunshot residue was found on the hand opposite where the bullet entered her temple, which would have required an almost impossible movement for Nancy to have fired the shot herself. She had been raped, there were bruises on her arms, on her thighs, in the vaginal area and traces of skin under her fingernails, a sign that she had tried to defend herself. She was taken to the hospital in a family-owned station wagon, naked and wrapped in a sheet. Afterward, Jaime went on the run.

Oliveira states that “there is now no possibility that he will be extradited, not even expelled or deported by the authorities.” That is to say that Jaime Saade, now 58, can continue to live peacefully in Belo Horizonte as Henrique Dos Santos Abdala. The Colombian government also sees extradition as unlikely. “The extradition treaty in force between Colombia and Brazil states that once the extradition of an individual has been refused, the surrender of the individual cannot be requested again for the same act for which he or she has been charged,” the Ministry of Foreign Affairs told Barranquilla-based daily El Heraldo in March.

Mestre refuses to accept this. And he will not countenance it. The law firm Quinn Emanuel Sullivan & Urquhart LLP, from its Washington office, is leading the efforts alongside Brazilian lawyers and the family to find a way to ensure justice is served before the end of Saade’s sentence. Upon hearing the ruling, Mestre wrote an open letter to the members of the Superior Court, which was published by local media and titled: A Colombian killer roams free in Brazil. As yet he has received no response. And if Mestre finally succeeds in his mission, what will he do? “Find a way to make him talk. I only want to know why. I went to the door and asked him to look after her. And look how he looked after her.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.