The year of quantum science: Promise and peril in the race for breakthroughs

A century after Heisenberg formulated his theory, the field has transformed our understanding of the physical world, yet many of its applications remain in development

The German physicist Werner Heisenberg took refuge a century ago on the small island of Helgoland (which today has 1,300 inhabitants) to escape his allergy. He was only 23 years old when, in that cold and windy environment, he formulated the principle of one of the theories destined to revolutionize the understanding of physics and promise a new world.

The centenary of this discovery has led the United Nations to declare 2025 the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology, an event whose realities and promises inspire both skepticism and enthusiasm. Without the window Heisenberg opened, today’s smartphones, computer circuits, and flat screens would not be possible. Without the counterintuitive principles of quantum mechanics, fields such as pharmacology, medicine, and metrology would not be looking toward a promising future. But the anticipated revolution still has a long way to go, which frustrates expectations, because, as in computing, it is the tool expected to definitively open all doors.

“It is clearly one of the most important scientific stories, and that is why it is capturing the attention of the media and the world in general,” says Jim Al-Kahalili, a British physicist of Iraqi origin and professor of theoretical physics at the University of Surrey, during an event organized by the Science Media Centre (SMC). Al-Kahalili compares it to the advent of artificial intelligence a decade ago: “It is going to change the world, it is going to transform all our lives. We’d better talk about it; we’d better have a good idea of what it is.”

Although the most popular example is illustrated by Schrödinger’s cat to explain the concept of quantum superposition (the animal can be alive and dead at the same time until observed), the path Heisenberg began is, according to the Surrey physicist, “more important than the theory of evolution.” “It has truly transformed the world,” he insists.

Quantum mechanics explains why chemical elements are arranged according to their properties, how electrons are organized around atoms, and the structure of matter. “It dictates the properties of atoms and, therefore, the nature of everything,” explains Al-Kahalili.

Its principles are very much present in everyday life. Semiconductors, the foundation of any modern electronic integrated circuit, became possible by understanding quantum principles. Heisenberg’s allergy paved the way for the computers and cell phones that are now part of everyone’s life.

And understanding reality at the smallest scales is the stepping stone to a new world. Quantum entanglement — the connection of two or more particles such that their states are inseparable regardless of distance — confounded Albert Einstein himself, who rejected it and called it “spooky action at a distance.” Yet, according to the British physicist, “it is the way our entire reality is intertwined, and, combined with other ideas in quantum mechanics, it will help us develop an entirely new set of technologies that are going to change the world.”

Peter Knight, physicist, professor of quantum optics, and researcher at Imperial College London, adds at the same SMC event that this superposition of entangled states, despite its fragility — any interference (noise) can disrupt it — “opens up all kinds of opportunities.” “It is the foundation of what we want to do in computing, but it is much more than that,” he explains.

In this context, he refers to the potential of quantum mechanics in fields such as imaging, metrology, and engineering. “It allows us to do truly important things, like measuring magnetic or gravitational fields, or imaging the brain,” he says.

Javier Prior, a physicist at the University of Murcia specializing in biology, thermodynamics, and quantum sensors, has developed a quantum system for detecting the smallest cellular-level alterations, working initially with pure nanometric diamonds. These diamonds contain particles that react to any anomaly in the development of the tiniest biological units, allowing the identification of dysfunction at its earliest stage or within a microfluid of the body. It is a microscopic beacon that sends signals when it detects the first physico-chemical sign of an incipient cellular storm.

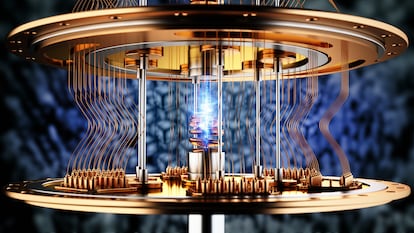

While Schrödinger’s cat is the most famous theory, the application with the most followers is computing. Knight is also optimistic in this field. “Over the past couple of years, there has been extraordinary progress in what is called error correction,” he states, referring to systems that address the deficiencies in qubit coherence, the quantum unit that exponentially multiplies computing capacity.

“A difficult problem could take the age of the universe to solve on a supercomputer, but using a quantum computer, it could be solved in minutes or hours,” says the physicist, who does not shy away from noting that, just as there are “wonderfully useful applications in commerce, banking, and financial technology, we are seeing malicious uses.” He is referring to a quantum computer’s potential to breach internet security, on which modern society depends.

Among the applications already in use, Knight highlights the use of quantum technology in brain imaging, which is currently applied to treat juvenile epilepsy, for oncological diagnostics based on imaging, or to measure the local gravitational field for use in topography. “We can build the most precise clocks, we can build systems that allow navigation without GPS… all of these things are happening,” he says. Al-Kahalili adds: “The applications can also be used to understand weather properties by incorporating quantum technology into satellite imaging.”

Among the more cautious researchers regarding this revolution is José Luis Salmerón, who has applied quantum processing models to propose medical treatments and predict sequelae. A professor of AI at Universidad CUNEF, researcher at the Universidad Autónoma de Chile, and executive at Stealth AI Startup, Salmerón believes that “we are still at a stage where many things remain to be defined, and there are aspects of technology and science that are not yet fully developed and that require some progress to become more usable.”

Salmerón questions the claims of quantum advantage, the point at which this computing can solve problems impossible for existing technologies. In this regard, he doubts that breakthroughs are imminent, contrary to the claims of Matthias Steffen, a physicist at IBM. “You can almost feel that we are getting there,” says the creator of IBM’s Starling model.

“The technological aspect still raises my doubts. I think there must be some advances that haven’t even been published yet and that could be quite interesting,” says Salmerón, when asked whether this year could mark the start of a new cycle.

A similar position is held by another group of scientists who are wary of the constant announcements of discoveries and milestones. These physicists believe that generating expectations that go unmet not only causes frustration but also threatens the credibility of the science and the fate of public funding.

Nonetheless, another group argues that each achievement, even if it does not fully materialize, keeps private investors engaged in the quantum race and opens new avenues.

One of the most recent steps in this direction was announced by Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), which has installed and is operating its first quantum computer at its data center in Tennessee.

ORNL will use the system to explore how quantum processing units (QPUs) can enhance high-performance computing in the same way GPUs have improved classical computing tasks.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.