More than a month without her daughter: the legal deadlock of an immigrant mother in Madrid

Catalina Delgado’s daughter was placed in a juvenile detention center when police discovered that she had been left alone while her mother went to work. She now faces a child abandonment case and a possible sentence of three years in jail

The life of Catalina Delgado, a 23-year-old Colombian, was turned upside down on the night of February 16, when she made the decision to leave her four-year-old daughter alone in her bed, surrounded by her toys and her mother’s cell phone, due to the fear of missing work. A few hours later, Catalina (an assumed name), was handcuffed in the bar where she worked and her daughter was taken to a juvenile detention center. She has not slept with her in 35 days and is six months pregnant. Her only access to a doctor has been in an emergency room. Catalina faces a trial for child abandonment — punishable by up to three years in prison — which has been delayed due to a judicial strike. Meanwhile, she calls her daughter at the center every day, but sees her only once a week, while being bounced from one institution to another. With no job, no money, no medical care and now without her daughter, Catalina is trying to survive in a country that is squeezing her more and more every day.

Catalina knows more about hardship than a girl her age should. She grew up in the department of Putumayo, on the Colombian border between Peru and Ecuador, the gateway to the Amazon. It is one of those corners of the world that environmentalists strive to save while armed groups terrorize the population. It is also the largest area of coca cultivation in Colombia, at around 31,000 hectares. Her family fled to Cali, about 18 hours away by bus. She returned years later with the father of her daughter. Shortly before deciding to leave the country with the girl and two of her four siblings, on a one-way flight to Madrid in November 2019, drug traffickers riddled the house where they lived with bullets. Nine months after landing in Spain she was denied asylum: her life was not considered in danger.

She could hardly have expected that worse would come in Madrid. “I swear this is the hardest thing I have ever experienced,” she says. Catalina is engulfed in the same spiral of misery in which thousands more like her live: without asylum, she has no papers; with no papers, she has no employment contract; with not contract, no paycheck, she has no means to rent an apartment in her name; without a registered address, she cannot register with the authorities; without those documents, she has no access to social benefits for her or her daughter or health care to monitor her pregnancy.

The police were called to Catalina’s home on the night of February 16 after a neighbor reported the girl’s cries on the other side of the wall. A co-worker who shared the apartment opened the door for the officers when he returned from work that night. From the phone Catalina had left by her daughter’s side, the officers located her working in a bar in the Villaverde neighborhood of Madrid. That night her daughter slept in a detention center and her mother, in a jail cell.

Since then, the legal process has been stalled. The judge’s verdict could leave Catalina with a criminal record, ending any chance of obtaining her papers and finding a better and more stable job. The Madrid regional authorities, which provisionally withdrew her guardianship of her daughter immediately, continues to study her case. “They are working on her reincorporation and looking for alternative means of support,” an official at the regional department for family affairs said.

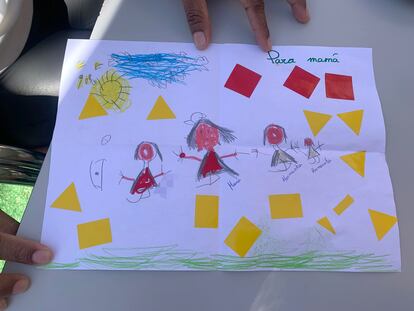

Every Wednesday, Catalina visits her daughter at 10am, taking with her jelly beans and a bag of Doritos. She is given one hour to spend with her daughter. The rest of the week, she has to make do with a 15-minute phone call every afternoon. “But, Mom, where are you?” her daughter asks every time they talk. “The police brought me here because you left me alone and I cried. You’re never going to leave me alone again, are you?” she says repeatedly. Catalina can’t bring herself to tell her that she is at home, in their home, for fear of confusing the girl further. The youngster is unable to go to school, to see her friends or to go to the park in the afternoons. “I tell her that I’m going to work and that she has to stay there,” Catalina explains.

But she hasn’t worked in a month. Her partner and father of her unborn child left Spain a week before everything exploded to look for a better-paid job. And now she is alone. Her only family in Spain are her brother and sister-in-law, who survive as best they can by working precarious off-the-books jobs to support their two children. On February 16, everyone she thought she could rely on failed her. A friend, as well as her brother and sister-in-law, are the main witnesses in her case, but there are also testimonies from the girls’ school and the child’s pediatrician. “I am not what they say about me. I am not a bad mother. This is all like a bad dream,” she says.

Catalina survives as best she can on what she managed to save over the last three years. She counts every cent in a country that is becoming more and more expensive, especially for foreigners without papers. A room in a shared apartment costs her €350 a month and she barely made €1,000 while working as a carer for seniors. The two people she cared for both passed away and she took the bar job as it was her only option. She had working there for less than a month when she was arrested. Now she fears that with her pregnancy it will be even harder to find work.

ECHR condemns Spain’s violation of parents’ rights

Catalina’s battle to recover her daughter is shared by many other migrant women in Spain. Just over a month ago, the High Court of Justice of Castilla y León, a region in Spain, ordered its family affairs department to pay €150,000 in compensation to a Bulgarian mother and her twin daughters for having withdrawn custody in 2016. The court ruling stated that the authorities acted with “huge disproportionality,” causing “trauma” for the girls, who were 12 at the time. In at least three other cases, the European Court of Human Rights has condemned Spain for actions that violate the rights of foreign parents and their children. In 2012, the same court ruled in favor of a Nigerian man who reported that the Child Protection Services in the region of Murcia had given his son up for adoption after the boy’s mother was deported from the country.

Experts consulted by EL PAÍS agree that the child protection systems in Spain fail to prevent people without resources from losing their children and point to a lack of support for these families. José Antonio Bosch, a lawyer with extensive experience in juvenile issues, handles many such cases. Bosch states that in Spain there are almost 36,000 minors under the guardianship of regional authorities, a number that he considers to be “extremely high.” The lawyer is critical of the protection mechanisms: “You can ask the regional government in Andalusia, for example, how many kilos of tuna fish pass through the Strait of Gibraltar and their average diameter and get a reply, but don’t even think about asking what the results of their child protection policy are. What happens to the children, what level of education do they achieve, do they receive vocational training… how can we evaluate a system in the absence of data and analysis?”

Bosch is not handling the case of Catalina and her daughter, but he frames it within a dynamic he knows only too well. “The government’s mission should not be to protect the child outside the home, but rather to protect him or her as far as possible within the family. That is the challenge, although what usually happens is to opt for the quickest and cheapest solution, which is to remove the children. It is an outrageous thing to go from living with a child to seeing him or her once a week. And government agencies take an extremely long time to decide on the child’s future.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.