New study reveals Mars has a solid core

Data from NASA’s Insight mission suggest that the red planet is much more similar to Earth than previously thought

Data from a U.S. probe that stopped working three years ago has just revealed the existence of a 1,200-kilometer-wide (740 miles) metal core deep inside Mars. According to its discoverers, this is the planet’s solid core — a finding that contradicts what was previously believed about our neighboring world. The discovery deepens the mystery of why Mars, once a blue planet with oceans, rivers, and possible forms of life, suddenly transformed into a desert where radiation would annihilate any surface life.

The U.S. probe InSight holds the distinction of carrying the first seismometer to another planet. The NASA mission began operating in 2018, recording ground tremors known as marsquakes. By 2022, after logging more than 1,000 quakes, frequent dust storms disabled its solar panels, ending the spacecraft’s operational life. Nevertheless, it managed to shed light on the internal structure of the planet for the first time.

According to InSight data, although Mars is a rocky planet like Earth, it differs in having no solid core — its core was thought to be liquid, composed mainly of molten iron. But on Wednesday, a team of Chinese and U.S. scientists presented a review of 23 quakes recorded by the probe. They focused on this subset because some seismic waves traveled through the planet from side to side, while others bounced roughly halfway.

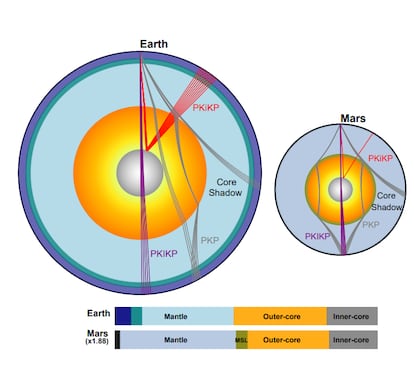

In 1936, a Danish woman named Inge Lehmann used signals from a similar earthquake in New Zealand to demonstrate that Earth has a solid inner core. Today’s scientists followed a nearly identical method to analyze the arrival of different seismic waves. Their results suggest that Mars’ inner core is solid and measures approximately 1,200 kilometers in diameter. The findings were published on Wednesday in Nature, a leading global science journal.

Five of the six study authors work at scientific institutions in China, and the sixth is a U.S. researcher. None were part of the main InSight science team. Over time, data from the mission became publicly available to the scientific community, and this group was the first to analyze these Martian quakes.

The new cross-sectional diagram of Mars — with an outer crust, mantle, liquid core, and solid inner core — bears a striking resemblance to Earth. In fact, the thickness of these layers is proportionally almost identical, raising even more questions about why these two rocky planets are so different.

Until now, it was believed that Mars ceased to be a habitable planet precisely because of its core. Scientists thought that, like Earth, Mars’ core had acted as a dynamo generating a magnetic field that, among other things, protected the surface from the Sun’s intense radiation. For reasons unknown, about 5 billion years ago this engine stopped, the outer atmosphere disappeared, and the planet lost its vast water reserves, becoming the frozen desert it is today. If life ever existed on the Martian surface, it probably vanished forever. Any remaining possibility for life would be far from the intense surface radiation, deep underground.

The conclusions of the Chinese and U.S. scientists do not convince all experts. Simon Stähler, a geophysicist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and a scientific collaborator on the InSight mission, says: “The data don’t convince me entirely, but it’s true that they have taken into account all possible confounding factors and the results hold up.” “I would say there’s a 30% chance that this is true, which is roughly the same as the existence of a solid core on the Moon [something the scientific community largely accepts].”

The new study highlights how difficult it is to study the interiors of planets, where materials are subjected to enormous pressures and extremely high temperatures. Stähler notes that laboratory data on the behavior of iron — the element thought to make up most of Mars’ inner core — suggest the temperature is too high to prevent it from melting. But he also acknowledges: “The data gathered in the laboratory on Earth do not represent the exact real-world conditions of the Martian core, so these new data may be showing us things about the behavior of materials that we don’t yet understand.”

The authors of the study argue that a solid core is possible because it contains not only iron but also lighter elements like oxygen. They estimate that the innermost part of the planet is around 1,700 degrees Celsius (3,092ºF). Considering that the layer immediately above is liquid and contains sulfur, oxygen, carbon, and hydrogen, a solid inner core is the most likely scenario, they argue.

Antonio Molina, a planetary geologist at the Center for Astrobiology in Madrid, welcomes the new findings, calling them “very interesting.” He explains: “This finding implies that Mars is more like Earth than previously thought. The authors propose that the solid inner core could comprise 0.18% of the planet’s total radius, while on Earth it is 0.19%. One possible interpretation is that Mars is older than we thought and that its core has already begun the process of crystallization. But this same process of continued activity produces internal activity that may imply that Mars is more alive. In any case, it is another step in understanding what planetary bodies are like and how they evolve.”

The key question is: if Mars and Earth share such similar internal structures, why are their surface conditions so different? Geologist Nicholas Schmerr, also part of the InSight team, suggests that while planetary magnetic fields depend on rotation, heat flow from the core, and the core’s composition, the crystallization of Mars’ solid inner core is very slow, which prevents the planet from generating a magnetic field. The mystery is far from resolved.

A very similar situation occurred on Earth. Danish mathematician Inge Lehmann’s original — and correct — proposal in 1936 was not confirmed until 1970, when more precise seismometers were installed across the planet.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.