First observation of a star’s interior opens unprecedented window into the birth of matter

The discovery of an unusual stellar explosion confirms the existence of a ‘cosmic onion’ with layers of chemical elements inside each star

“The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies were made in the interiors of collapsing stars. We are made of starstuff,” proclaimed American astrophysicist Carl Sagan in his famous book Cosmos almost half a century ago. A team of scientists has now been able to peer into these stellar bowels for the first time, the chaotic forge where the chemical elements that make up human beings and everything around them are formed. “I was dazzled,” recalls German astrophysicist Steve Schulze, who led the research.

To understand the significance of this discovery, we must go back to the Big Bang that gave rise to the universe 13.8 billion years ago. In the first three minutes after the Big Bang, almost all of the universe’s light atoms were formed, especially the ever-present hydrogen, the accumulations of which form stars. In the interior of a star, the temperature and pressure are so high that hydrogen fuses and forms increasingly heavier elements, starting with helium. The combination of silicon and sulfur, for example, produces iron, the heaviest atom that can be generated inside a star.

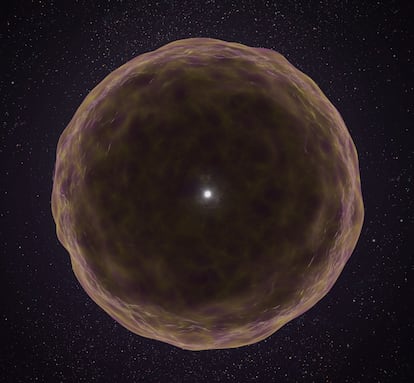

The result is a kind of “cosmic onion,” a term commonly used by astronomers. “This process transforms the star into a layered structure: hydrogen on the outside, then helium, then layers of carbon/oxygen, magnesium/neon/oxygen, oxygen/silicon/sulfur, and finally iron in the center. Therefore, the silicon- and sulfur-rich layer is buried beneath many other materials and is inaccessible under normal circumstances, making it almost impossible to observe directly,” notes Schulze, of Northwestern University in Evanston, Texas.

In September 2021, a telescope located at the summit of a Hawaiian volcano recorded the spectrum of light emitted by a supernova, the explosion of a star. The explosion, which occurred 2.2 billion light-years away and was called SN 2021yfj, was not just another supernova. The device captured the phenomenon at an extraordinary moment, just as the star was stripping away its outer layers, allowing a glimpse into its interior. “At first, we didn’t know we had discovered a star stripped to the bone. I was astounded when Professor Avishay Gal-Yam of the Weizmann Institute of Science [in Israel] concluded that we had observed silicon, sulfur, and argon,” Schulze recalls. His discovery was published Wednesday on the cover of the journal Nature, a leading international science publication.

Schulze, born in Halle, Germany 45 years ago, emphasizes that “more than one billion stars” are known in the Milky Way galaxy in which Earth is located and in its neighboring Magellanic Clouds. Most of these stars retain their hydrogen layer upon death, but a minority lose this layer or even the deeper helium layer before exploding into a supernova. This surface stripping can occur due to strong stellar winds, eruptions, or interactions with another star, but a virtually complete stellar stripping has never been detected.

“No star in the Milky Way or the Magellanic Clouds is known to be stripped down to the oxygen/silicon layer. The discovery of supernova SN 2021yfj indicates that rare and very extreme stripping processes exist,” argues Schulze, who worked at the Institute of Astrophysics at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile until a decade ago. The fusion of chemical elements heavier than carbon only occurs in stars that are at least eight times the mass of the Sun, earning them the designation massive. “This is the first time we have observed the inner layers of a massive star, which is important for testing and improving our models of stellar evolution. Furthermore, this discovery provides us with information about the formation of silicon and sulfur in massive stars,” adds Schulze.

The German astrophysicist’s explanation echoes another similar thought by Sagan, this time from his television series Cosmos: “The silicon in the rocks, the oxygen in the air, the carbon in our DNA, the gold in our banks, the uranium in our arsenals, were all made thousands of light years away and billions of years ago. Our planet, our society, and we ourselves are built of star stuff.”

Physicist José Ángel Martín Gago’s team has built a €4 million machine in his laboratory to simulate the death of stars at the Institute of Materials Science in Madrid. Martín Gago and his colleague Gonzalo Santoro, from the Institute of Fundamental Physics, celebrate the new discovery in a joint assessment sent to this newspaper. “This observation confirms the layered structure of supernovae, which is the model that has been used to describe them, although until now it was not clear whether it was valid. Confirming this model is very important for describing stellar evolution,” they state.

Supernovae and red giant stars are essential objects in the formation of cosmic dust, the two Spanish researchers emphasize. “This study provides fundamental information for understanding how chemical species form and evolve in the universe. At the level of laboratory astrochemistry, this work opens new avenues, as it provides empirical values for the abundances of silicon and sulfur that could be used to recreate in the laboratory the conditions for the formation and evolution of molecules rich in these elements,” they explain. “This approach will allow progress in the modeling of chemical reactions and a deeper understanding of the processes of cosmic dust formation in space,” they add. The discovery of the naked star offers an unprecedented window into the creation of the stellar substance from which humans and everything else are made.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.